For many Portlanders, life has come to a halt during the pandemic. But in some parts of the state's court system, it's still business as usual.

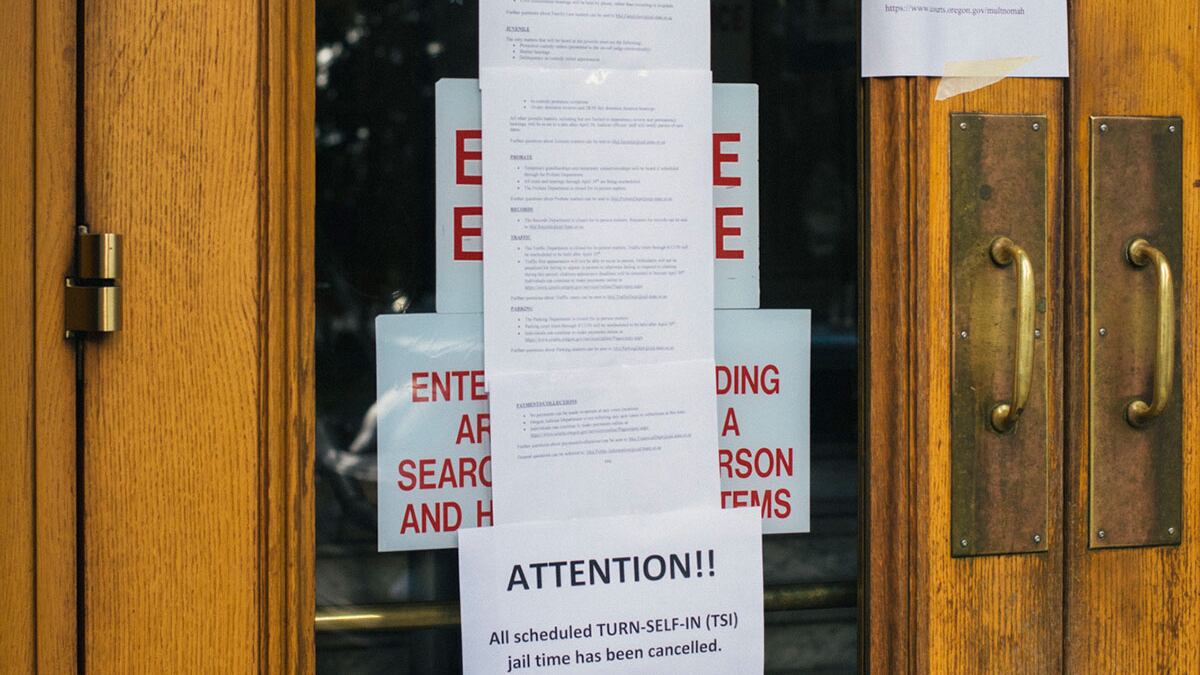

Back on March 16, Oregon Supreme Court Chief Justice Martha Walters announced that courts statewide would postpone nearly all hearings for defendants who weren't in custody in order to stem the spread of COVID-19, with an exception for essential hearings.

"The nature of this public health emergency has led me to order the postponement of most trials and court hearings," Walters said in a statement. "We will do our best to provide people their day in court when we can safely do so, and we will pursue options for continuing our work without requiring in-person appearances, but at the present time, limiting the number of people coming into our courtrooms and courthouses is paramount."

But the state's online court docket shows dozens of hearings scheduled in Multnomah County courtrooms between now and May 14. Chris O'Connor, a Portland criminal defense lawyer, says not all judges are following Walters' directive.

Instead, he and other defense lawyers tell WW, judges are latching onto the small amount of wiggle room Walters' order left them to keep making defendants show up at the courthouse.

WW has viewed a stream of emails between Multnomah County circuit judges and both prosecutors and defense lawyers that show confusion about Walters' order and how it is or is not being followed.

"When the chief justice says to postpone everything, why isn't everything postponed?" O'Connor says. "They're still having 15 people at least gather in a room at a time. Yesterday, I was in a room with 15 people, waiting. There's still witnesses, presiding officers, court staff all still have to show up."

Multnomah County Chief Criminal Judge Cheryl Albrecht determines the procedures for the county's criminal court hearings. She tells WW that any in-person hearings being held are necessary.

"I would disagree that we are holding nonessential hearings," Albrecht said in an email to WW. "We have carefully reviewed Justice Walters' order and believe all of the hearings we are holding comply with that order."

Albrecht says the court is acting in compliance with April 10 guidelines set forth by Multnomah County Presiding Judge Stephen Bushong. She pointed to a memo she sent judges, telling them to postpone cases for some defendants who weren't already in custody and hold many other hearings via phone.

Yet Multnomah County criminal judges are still holding in-person hearings, some for out-of-custody defendants, court dockets show. On April 14, for instance, two out-of-custody defendants will appear before Judge Eric Dahlin and Judge Andrew Lavin.

Every Multnomah County courtroom is set up differently, O'Connor says. Some rows of the gallery are closed off entirely to maintain social distancing, and tables have been moved farther apart. Many people are wearing personal protective equipment, though some staff are not. But in the Justice Center courtroom, where attorneys speak with or whisper to clients, O'Connor says, "It's impossible to maintain distance, although people are certainly trying."

Stacey Reding, a lawyer with Multnomah Defenders, says making low-level offenders appear in court during the pandemic is unnecessarily risky.

"I have been frustrated with our court's failure to just do blanket set-overs of these dockets, risking people appearing in person for low-level offenses," Reding says.

Aside from the fact that holding nonessential hearings runs counter to the chief justice's order, O'Connor says continuing to conduct regular court proceedings is troubling for two reasons: If people are still showing up in person for unnecessary hearings, their risk for exposure to COVID-19 increases. And if more warrants are issued and more rulings are made, more defendants could be sent to jail—the very place where many states are trying to reduce the number of people behind bars so they won't be trapped in close quarters during the pandemic.

Currently, 726 inmates are locked up in the Multnomah County Jail. That's fewer than usual. But other cities across the U.S. are releasing hundreds of inmates—primarily the elderly or medically vulnerable—to mitigate the spread of COVID-19.

Erious Johnson Jr., a criminal defense lawyer, says Multnomah County judges have been good at arranging conferences over the phone. That said, he was just in court on Monday and noticed a lack of personal protective equipment among court staff. "I don't know if they've been requiring face masks and gloves," Johnson says.

Multnomah County district attorney spokesman Brent Weisberg says the court has scheduled most hearings by phone.

"We have been working carefully and expeditiously with our local public safety partners, including the local defense bar, and others to do everything we can to balance the needs of public safety, public health and to serve crime victims," Weisberg said in an email to WW.

Albrecht says nearly all nonessential hearings for defendants on bench probation can be conducted over the phone. Appearances are waived if attorneys can show the court they are in contact with their clients and can communicate upcoming hearing dates to them. Citations are issued only if an attorney can't do that.

O'Connor says many of his firms' clients are homeless and struggle to telephone into their hearings. "It's halfway there, but not quite," O'Connor says. "They're still issuing warrants if you don't participate in that."

He argues that the balance Multnomah County courts are trying to achieve looks more like a guessing game.

"All the courts all over the state are left to interpret that themselves," O'Connor says. "It's like a game of chicken."