Portland pollster John Horvick thinks Oregon Democrats have a math problem. The party’s leaders will have trouble securing five of the state’s six congressional seats without engaging in some contortionist geography.

“I assume the standard WW reader doesn’t like gerrymandering and wants to get to five Democrats” in the U.S. House, Horvick says. “The fact is that those two are just incompatible.”

Some context: Oregon’s population gains in the 2020 U.S. Census guaranteed the state would add a sixth seat in the U.S. House of Representatives. The increase comes as all states redraw congressional boundaries, as they do every 10 years. U.S. Supreme Court rulings say that House districts must be as close to equal in population “as nearly as practicable.” How states achieve equality—that’s politics.

State lawmakers get first crack and have formed bipartisan committees to draw the new boundaries. House Speaker Tina Kotek (D-Portland) and Senate President Peter Courtney (D-Salem) even invited citizens to submit their drawings of where the districts should lie to the committee by Sept. 7.

Horvick, political director at polling firm DHM Research, started sketching two weeks ago, using an interactive website called Dave’s Redistricting (davesredistricting.org). He quickly recognized a puzzle: Democrats, who now hold four of five U.S. House seats, will struggle to add a fifth without obvious gerrymandering.

“It’s quite reasonable to think we’re picking up the sixth seat because Democrats moved to the state,” Horvick says, noting that much of Oregon’s population gains came from college-educated transplants, a mostly blue constituency. Democrats continue to build a massive voter registration advantage—now nearly 300,000—over Republicans. “The assumption was that the sixth seat would be Democratic. But I think it’s pretty tough to get there. We’re very likely to add a seat that’s going to be Republican.”

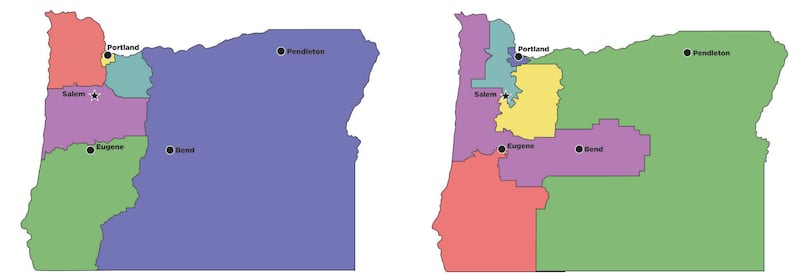

Horvick says the dilemma boils down to this: Democrats cluster in Willamette Valley cities. The guidance given to lawmakers says districts, in addition to being comparable in population, should take into account geographic and political boundaries, be connected by transportation links, and not split communities of interest. Those guidelines will make it difficult to distribute Democrats into five districts without creating the kind of tortuous shapes good government types associate with unprincipled opportunism. Horvick walked WW through two maps to help readers brace for disappointment.

Map 1: Makes Geographic Sense

In this rendering of six districts, the lines are drawn in compact shapes that reflect known regions of the state while having roughly equal populations. “That will seem perfectly reasonable, visually, to people,” Horvick says. But the result on election days won’t: In this map, three of the five districts would have a majority of registered Republicans.

Map 2: Makes Partisan Sense for Democrats

In this map, Democrats would have a puncher’s chance at winning five of six seats. The cost? Districts that look unnatural to Oregonians—with East Portland and Gresham lumped in with Pendleton and Malheur County, and another L-shaped district linking Bend to the coast in order to scoop up enough Dems. Horvick says a glance at this map may explain why Kotek gave Republicans equal say at the redistricting table: “At the federal level, you’re probably not giving up that much,” he says. “It would be very difficult to get anyway.”