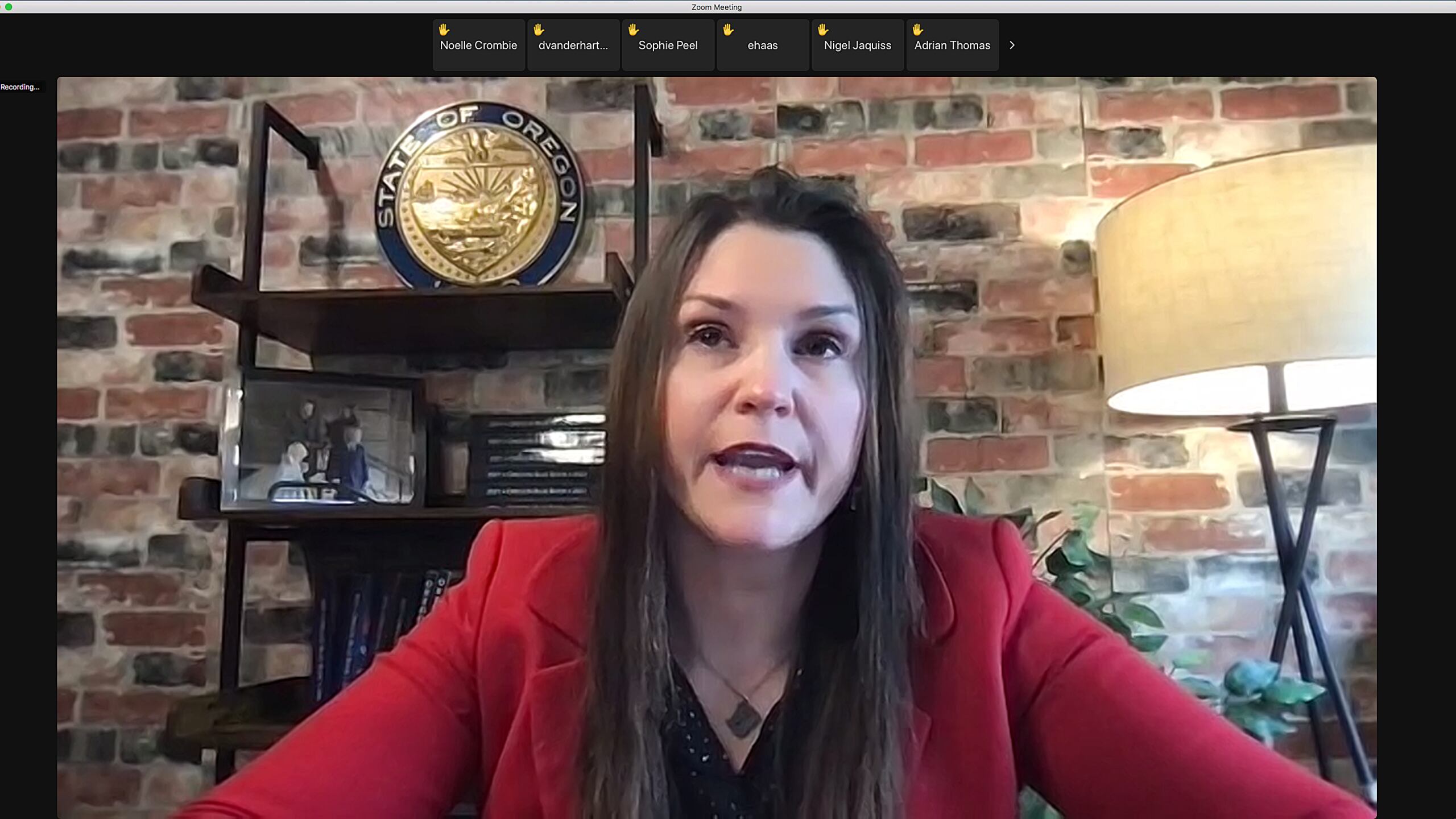

Oregon Secretary of State Shemia Fagan answered questions about her controversial cannabis consulting contract for the first time Monday morning, shortly after releasing a copy of the $10,000-a-month contract with the founders of the embattled dispensary chain, La Mota.

The contract, which Fagan shared only after intense pressure in the past four days since WW first reported her moonlighting gig, shows that in addition to the $10,000 a month, Fagan stood to earn an additional $30,000 for every cannabis license obtained by the company outside of Oregon and New Mexico.

The contract says little about what the work actually entailed. Fagan told reporters Monday she’d begun building a spreadsheet based on her research of cannabis opportunities in other states.

That means the elected official in charge of Oregon’s Elections, Audits and Corporation divisions was making more from her private consulting gig than she was from her full-time statewide-elected position. What’s more, La Mota’s owners, Aaron Mitchell and Rosa Cazares, were prominent political donors to Fagan’s campaign and records show that she repeatedly encouraged state auditors to consult Cazares during an audit of the Oregon Liquor and Cannabis Commission.

Below are six takeaways from Fagan’s Monday press conference, which Fagan ended prematurely despite reporters’ requests that she finish answering questions before calling it quits.

1. Fagan did not know La Mota’s owners, Aaron Mitchell and Rosa Cazares, before her 2020 campaign for secretary of state. Fagan says she met them at a breakfast after she had announced her run. That is potentially significant because Oregon ethics laws prohibit public officials from using their public office for private gain. Fagan, an employment lawyer whose bar license went inactive when she took office, claims that Mitchell and Cazares hired her to research cannabis opportunities in other states.

2. Fagan spoke with the lieutenant governor of Connecticut, Susan Bysiewicz, during the course of her work for Mitchell and Cazares in scoping out cannabis regulations in other states. “I talked to a friend of mine in Connecticut just to ask who would be someone for a cannabis company to talk to if they wanted to get the lay of the land,” Fagan said. That means Fagan had direct access, on behalf of La Mota, to the second-most powerful state official in Connecticut to ask about expanding its business. (Records show La Mota has already attempted to expand to New Mexico and Michigan.)

3. Fagan says her salary as secretary of state—$77,000—is “not enough to make ends meet.” She added: “This is my financial reality, and that’s why I followed Oregon government ethics guidelines and began earning supplemental income in my free time.”

4. Fagan says she “didn’t know about [La Mota’s] issues” when she took the contract in February. “I later learned by reading WW’s reporting about the troubling allegations against the owners. I believe the right thing for me to do is redirect as much as their political donations as I have left in their PAC,” Fagan said. However, Fagan did know about the millions in tax liens filed against the couple and their companies on March 24, when WW first reached out to Fagan about the chain. She did not terminate the contract then, nor did she pledge to give their contributions to charity until May 1—more than a month after WW first told Fagan about the chain’s issues.

5. Despite the $10,000 a month La Mota’s owners paid her, Fagan last week called the work performed for the contract “minimal.” On Monday, however, Fagan backtracked and said she meant it was minimal “compared to my secretary of state” position. She says she spent about 15 hours a week performing work for Cazares and Mitchell.

6. Records show Fagan repeatedly pressed auditors as early as January 2021 to speak with Cazares in determining the scope of an audit of the Oregon Liquor and Cannabis Commission, an audit that she later recused herself from in February 2023 because of the contract. “That’s customary. It’s very regular in the audits because auditors want to have a broad landscape of who they’re asking about,” Fagan said. “I’m not deeply involved in the audit work.” But Fagan oversees the Audits Division. That means the Audits Division director and all audit staff are her subordinates. She emailed the director in 2021 requesting that he speak with Cazares about the audit.

Read all of WW’s stories about Fagan’s moonlighting here.