This story was produced by the Oregon Journalism Project, a nonprofit newsroom covering the state.

When it comes to education, Oregonians cherish local control. Yet increasingly, experts say local control is one reason so many Oregon kids can’t read.

Over the past decade, as the Oregon Journalism Project has previously reported, the state’s fourth grade reading scores have sunk to the bottom of national rankings.

Meanwhile, a handful of once-lagging Southern states, in particular Mississippi, have surged into early literacy’s top tier.

Those states succeeded by mandating statewide, multitiered “science of reading” systems—early screening, phonics-based curriculum, universal teacher training, and consequences for not making progress. Mississippi now ranks No. 1 in fourth grade reading, adjusted for demographics, according to an analysis by the Urban Institute.

Oregon’s rank: 50th.

That failure is expensive: Oregon kids lag badly behind their peers in other states in an evermore competitive world. And it means that the single biggest line item in the state’s general fund budget is, at least for now, a lousy investment.

It’s not that Oregon hasn’t attempted to fix things. In 2023, for example, state lawmakers approved $140 million in a literacy funding bill to encourage the state’s school districts to use science-based reading methods.

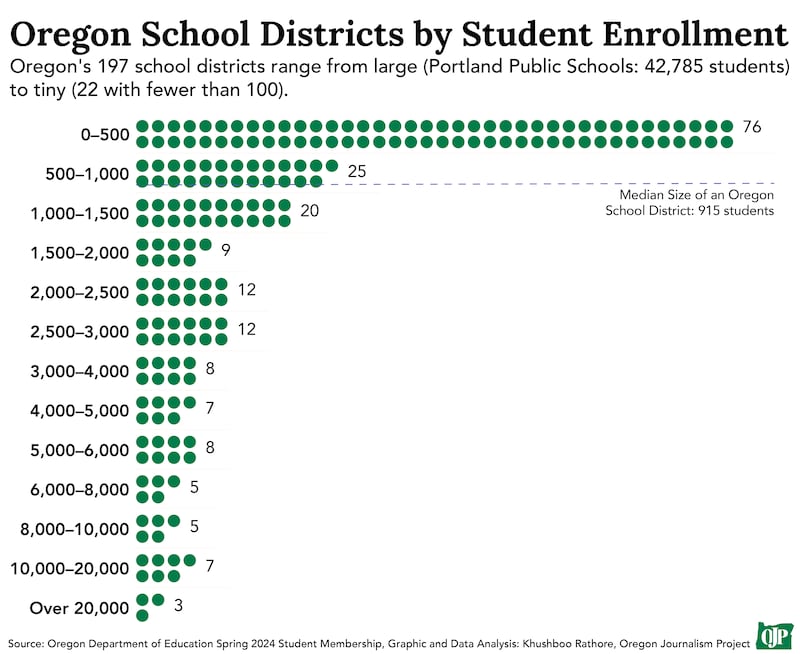

But unlike Mississippi and other southern states, Oregon gives its 197 separate school districts wide leeway in how to spend the new dollars in the name of “local control.” Half of the districts are smaller than 915 students, including two dozen smaller than 100 students.

READ MORE: OJP’s “Oregon Schools: What Went Wrong”—Schooled by Mississippi

Oregon’s devotion to local control, instead of mandated statewide educational policies, has hindered reading recovery efforts that have worked elsewhere, according to some school leaders, experts, and advocates, and a review of education research.

Oregon “does not really have a state educational system,” says Sarah Pope, executive director of the nonprofit Stand for Children Oregon. “We have a series of 197 school districts by and large doing 197 different things, and the state is pretty dang silent on their expectations for what schools do and deliver but where local control sort of trumps everything else.”

Local control in Oregon means, among other things:

- The Oregon Department of Education recommends high-quality reading curriculum but doesn’t require it, unlike Mississippi.

- In many districts, less than half of early readers take the statewide exam, which hamstrings Oregon’s ability to understand how well schools and districts are performing, and compare them to their peers across the nation. Oregon is one of only two states that by law must remind parents each year in writing that their kids can opt out of achievement tests, a decade-old law pushed by the teachers union.

- Oregon sends its K–12 school funding to districts with few strings attached rather than targeting the state’s neediest schools, as Mississippi, Louisiana, Tennessee, and other states in the “Southern surge” do.

“I think our culture in Oregon is one where we’re Western, we’re independent, we want to be left alone in our districts,” says Portland’s Chris Minnich, former executive director of the Council of Chief State School Officers.

He and others point to an Oregon culture that emphasizes individual choice: from the state motto “she flies with her own wings” to a robust initiative system that allows citizens to make laws, such as the first-in-the-nation assisted suicide law and vote by mail.

Angela Uherbelau, founder of Oregon Kids Read, a reading advocacy group, says the Oregon Department of Education and elected officials defer to local control as an excuse for not using their authority to direct funding to schools with a continued history of low reading scores.

“It’s not local control,” she says, “it’s local abandonment.”

Using discredited teaching methods

One of the most damaging consequences of local control is that many of Oregon’s 197 school districts have ignored best practices for decades when it comes to teaching kids how to read.

Researchers established long ago that phonics-based instruction is the best method for getting all children to read, the National Reading Panel concluded in 2020 after synthesizing 40 years of research.

In Mississippi, officials at the state level have absorbed best practices and insisted since 2013 that all districts use a phonics-based curriculum. In Oregon, districts big and small have used discredited “balanced literacy” curricula for years.

Even today, the Oregon Department of Education recommends but doesn’t require school districts to use state-vetted reading curriculum based on the science of reading.

The department maintains a list of workbooks and texts that it expects districts to choose from. But a district can ignore the list and choose its own, state officials say, as long as the district goes through “a local process” and its school board—made up of volunteers who often lack any background in education—approves the selections, which are supposed to align with the science of reading.

About 80% of districts told ODE they have selected core reading texts from the state list, but that doesn’t mean they are using them in the classroom.

A case in point: Ronda Fritz, a former elementary teacher and currently an associate professor at the College of Education at Eastern Oregon University, was on a tutoring assignment at a La Grande elementary school a year or two ago when she spotted the latest reading textbooks, selected from an ODE-approved list, stacked unused on a closet shelf.

It wasn’t a surprise. “I’ve been in schools where I’ve seen teachers have those curriculums still in the shrink-wrap,” she says.

Districts may tell ODE they’ve selected the right reading curriculum, but not all students in Oregon classrooms are getting the benefit of research-proven reading instruction.

“We do site visits and monitoring, but with over 550,000 students and a handful of literacy specialists, it’s not going to be reasonable, of course, for us to be in each and every classroom,” says Charlene Williams, director of the Oregon Department of Education.

Everybody’s opting out

Although some educators and families abhor standardized testing, experts say well-designed tests offer vital feedback on whether children are learning and whether teachers and the curriculum are effective.

But local control allows Oregon students to opt out of tests at an extraordinary rate—higher than all but seven other states.

At best, that’s a missed opportunity. At worst, it’s a cynical attempt to downplay adults’ failure to educate children.

Many educators and experts say tests are a necessary statewide accountability tool. They not only measure a school’s academic progress, but also help identify students who need special attention.

“What gets measured, gets done,” says Kymyona Burk, the former literacy director at the Mississippi Department of Education who implemented the state’s massive 2013 education reboot.

Oregon lawmakers undid this accountability tool a decade ago by passing a testing opt-out law. It required districts to remind parents in writing each year that they had the right to refuse to have their kids take the state test for any reason, without consequences.

Oregon, along with Utah, became the only two states that had such an aggressive opt-out policy, according to a report by ACT, the national testing company. Opt-out rates started to climb.

As a result, Oregon is one of only eight states that fall below the federal guidelines that require 95% of students to take the statewide proficiency test. In some rural Oregon districts, such as Marcola in Lane County, Paisley in Lake County, and Harney County Union, more than half of students opt out of testing.

This can create a problem for one of ODE’s key accountability measures—its district and school “report cards.” The online reports detail each district and school’s absenteeism, graduation rates, and test scores in third and eighth grade reading and math, among other measures.

Many parents rely on the report cards to determine how well their local school is educating their children, but the report cards do not include opt-out rates and can easily mislead.

Last year, for example, the Fossil School District, in Wheeler County, which includes an online distance learning program with about 2,400 K–8 students, had one of Oregon’s highest third grade reading scores—67% proficient, far above the state average of 41%.

But that accomplishment is less impressive when parents understand that only 17% of third graders took the test, the highest opt-out rate in Oregon.

Dan Goldman, superintendent of the Northwest Regional Education Service District, says not being able to accurately assess educational progress is “a fundamental flaw, maybe a fatal flaw, in the state of Oregon. We have denigrated and set a really negative culture around assessment.”

He adds, “It’s like only taking half of your doctor’s recommendation for treatment, and then blaming the doctor for not getting better.”

One of the biggest supporters of local control and having such an aggressive opt-out is the Oregon Education Association, the 41,000-member teachers union.

“Parents need to have other ways to show that their children have achieved mastery,” OEA argued in testimony for the opt-out bill. The union generally opposed standardized testing, concerned it could be factored into teachers’ annual performance reviews.

OEA is the strongest voice in public education in Salem. The union has spent an average of $2 million in recent general election cycles. Historically, its members have given more money per capita than teachers in just about any other state. OEA strongly supported the 2025 legislation that made Oregon the only state in the nation where striking public employees can get unemployment benefits.

In an interview with OJP, OEA equity director Monica Weathersby said the union would not support reducing local control in exchange for a centralized reading recovery program like Mississippi’s. OEA also opposes prioritizing funding to the neediest schools. “Picking and choosing is not going to solve the issue,” she said. “There are needy students all over our state. We all need more money.”

As for teachers using a mandated reading curriculum, Weathersby said, “We support teacher autonomy.” And she accused Mississippi of “gaming the system” by retaining struggling third grade readers so they won’t show up in the national testing for fourth grade reading.

The state pays, but locals have the say

In many states, school districts are funded primarily by local property taxes, which is a basis for local control. That used to be the case here, until Oregon capped property tax growth with Measure 5 in 1990 and Measure 50 in 1997. Now about two thirds of K–12 districts’ funding comes from the Legislature, based on student enrollment.

“One of the things we do in Oregon often is to say, ‘Oh, here’s your school funding, district. You guys figure it out,’” Minnich says.

In a response to the state’s continued early literacy crisis, Gov. Tina Kotek and the Legislature passed the Early Literacy Success Initiative in 2023, which earmarked an additional $140 million for schools to use phonics-based instruction, train teachers in best practices, and hire reading tutors and coaches.

But rather than mandating how the money got spent, the new law provided a voluntary grants program “to incentivize” districts “to embrace” science of reading curriculum. In other words, all carrot, no stick.

Some advocates felt ODE should direct funding to the poorest-performing schools rather than letting local districts call the shots.

Oregon Kids Read argued that millions should go first to the 42 “most neglected” schools—both rural and urban—that have stayed at the bottom in reading for more than six consecutive years.

But ODE and lawmakers decided otherwise. J. Schuberth of Oregon Kids Read worked on the legislation and said ODE officials didn’t want to upset local districts by targeting the money. “They said it would be shaming the schools,” Schuberth says.

The Democratically controlled Oregon Legislature has not exactly charged to the rescue of children who haven’t been taught to read.

Former state Sen. Michael Dembrow (D-Portland) chaired the Senate Education Committee and helped craft the 2023 early literacy initiative.

But he acknowledges he didn’t appreciate how leaving reforms up to local districts would fail to bring change.

“I only came to realize fairly, fairly late in my legislative tenure that it was all kind of voluntary,” he tells OJP, “and that there were many districts that were just not taking advantage of that [money] because they didn’t want to be seen as underperformers. And the department wasn’t forcing them to get in the program. And when I found out about that, I found that really unacceptable.”

Oregon Kids Read founder Uherbelau finds the Legislature and the governor’s hands-off approach infuriating.

“The state has actively turned its back on some of our districts, rural districts, districts with higher numbers of kids in poverty,” she says. “And especially when you look at other states like Mississippi or others that have been successful, part of why they’re successful is, they target the money where it’s most needed.”

Who will step up?

Burk, who implemented Mississippi’s ambitious reading recovery plan, says Oregon can get its early readers back on track with a centralized program. “I think it can happen anywhere. We’ve seen the improvement that’s happening in Indiana, in Tennessee, and of course, Louisiana, and Alabama, and other places.”

But it would require “the Department of Education to get it done, schools and school districts to buy in, and be open to shifting their practices,” she says.

In addition to OEA, reformers would have to battle the Oregon School Boards Association, which would resist, at least for now. “Our local school leaders are best positioned to understand the unique needs and challenges of their communities and to identify the most effective way to reach their student[s],” OSBA president Emielle Nischik said in a statement.

Wresting significant control from local districts would require a level of courage state officials have rarely shown—even though K–12 funding represents the single biggest line item in the state’s general fund budget.

In Oregon, the governor could issue executive orders or push legislation giving ODE the power to mandate change within Oregon’s 197 districts.

Asked by OJP if local districts have too much control and the state too little, Gov. Kotek didn’t answer directly. She said she expects local school districts to be good partners on early literacy “and so far, so good.”

“We have been very clear that districts should be picking evidence-based curriculum,” she said—using “should” instead of “must.”

Williams said ODE is “doing all that we can to ensure that these kids can read with the tools that we have.”

Standing in the way of such reforms is Oregon Senate Education Committee Chairman Lew Frederick (D-Portland). Frederick rejects the building blocks of the Southern surge—more state control, standardized reading curriculum, and proficiency assessments.

In fact, Frederick, who briefly worked as a teacher and later spokesman for Portland Public Schools, tells OJP he doesn’t even believe the Southern surge is real.

“I am skeptical of those states,” he says, based on a family member from Mississippi who told him, “Don’t believe the hype.”

Frederick, a driver of the testing opt-out bill, not surprisingly discounts standardized testing. “It’s flawed at best,” he says. If reading is taught in a standardized way, Frederick adds, “we get standardized people.”

“If I want to find out how well kids are reading, I’d look at how many books are checked out of the library,” he says.

The vice chair of the Senate Education Committee, state Sen. Suzanne Weber (R-Tillamook), a former elementary teacher whose son struggled with reading, disagrees with Frederick.

She wants Oregon to take the Mississippi toolkit and apply it statewide. Give the state more power over local districts, even use Mississippi’s controversial third grade retention policy for kids who need more instruction before moving to the next grade.

“What we have done in education is almost a sin,” Weber says. “We have never spent the time to figure out what works.”

If you are a student, parent, teacher or former teacher, school administrator or policymaker with ideas on how to answer these questions, we want to hear from you. Please share your thoughts and how to reach you by clicking on this link.