It’s a chilly Wednesday afternoon, and I’m standing on a traffic median near the intersection of Northeast Sandy Boulevard and Burnside Street, sporting filthy jeans, work boots, a sweatshirt, a yellow slicker, a ratty old ballcap and a three-day stubble.

My mission: to figure out whether Portland's growing population of roadside panhandlers are lonely victims of an uncaring world or organized hucksters milking sympathy from gullible motorists.

Drivers briefly meet my gaze as they cruise past, their eyes registering either pity or disgust. When the light turns red, and the traffic slows to a stop, I can see them scanning my cardboard sign:

"I NEVER SAW THIS COMING. ANYTHING HELPS."

I am not alone. Across the street, a young guy with stripes tattooed down his face performs an energetic dance on the sidewalk, flying a sign that says, "HELP A HUNGRY HOMELESS KID."

"Quit stealing my fucking traffic!" he yells, glowering at me from under his shaggy bangs. I stand my ground. A few minutes later, a Saturn pulls up and a middle-aged gentleman gives me a handful of change. I pocket the coins and stare ahead, and the light changes back to green.

Suddenly, a wall of a man looms up beside me—standing 6-foot 4, with a dirty stocking cap, an angry scab across the middle of his nose, and shoulders like anvils.

"How long you been in town?" he demands.

"A while," I tell him.

"Well, there's some people been here longer than you, and this is their corner," he growls, jabbing a meaty index finger toward my chest. "I'm just telling you how it is. You got half an hour."

He stalks off across the intersection and holds up his sign: "HOMELESS. HUNGRY. GOD BLESS."

God bless—the universal sentiment of Portland's latest streetcorner industry, where sympathy is measured in quarters and sorrow is scrawled with a Sharpie. In the last few years, roadside panhandlers (known on the street as signers or flaggers) have spread like dandelions in a ditch, populating on-ramps, off-ramps, interchanges and highway dividers, clutching cardboard signs that proclaim their plight.

"You see it everywhere," says Portland Police Sgt. Brian Schmautz.

Nobody is sure of their exact numbers. But an unscientific tally conducted by WW last month yielded a count of 90 signers in the Portland metro area.

They are old and young, male and female, hopeful and pathetic, roadside ramblers just passing through and neighborhood regulars who are here to stay.

Their earnings, like their stories, vary dramatically. According more than a dozen interviews, however, a typical day's take ranges from $10 to $35 (although it's worth pointing out that flaggers have a strong incentive to downplay those figures—no one's going to give money to a prosperous beggar).

You might think the reason a particular individual flies a sign at a particular intersection at any given moment is governed by chance. In fact, flagging is anything but random. It is a profession with its own rules and hierarchies. Ninety flaggers, each earning $35 a day, pencils out to more than $1 million a year. Chickenfeed by your standards, maybe, but it's enough money to spawn careers, cartels, competition—and enforcers.

A good location is the flagger's stock in trade. Choosing well means the difference between earfuls of insults and immediate, untaxed cash. One of the better spots in Portland is the grimy curb at the foot of the Banfield Freeway's 43rd Avenue off-ramp, which is controlled—or shared, if you prefer—by a small cartel.

"We organized this like a business," says Ted Sheppard, a short, wiry 55-year-old flagger, with quick eyes, a clipped, white goatee, and an angular face that opens into a mischievous grin whenever he speaks. He flies a white plastic sign that reads "OUTDOORS NEED HELP. PLEASE ANYTHING HELPS. GOD BLESS."

"We have the capacity to make life difficult," he jokes, referring to the tactics signers use to guard a lucrative corner. They may cajole, hassle, intimidate, fly their own sign in close proximity, even sleep at the spot in an effort to force an intruder out. Though it's rare, violence isn't out of the question, either.

Sheppard says he's been on the streets since last April, when police impounded his van. It was not his first brush with the law. His convictions span 20 years, for crimes such as possession, manufacture and delivery of a controlled substance; burglary; fraud; and forgery. But he's been felony-free for the past six years—ever since he started signing.

"It gives you a lot of time to appraise your life," he laughs. "It takes all day to meet basic needs."

For Sheppard—a heroin addict—the needs are a revolving sequence of food, cigarettes and drugs. A typical day's take is $15 to $30, he says. Some days he buys methadone for $9 a pop at Portland Metro Treatment Center. Some days he pays $40 for three balloons of heroin from a street dealer.

"I'm doing whatever I can do to stay out of trouble," he says, his voice ringing with sincerity.

Sheppard works the early shift, starting at about 4:30 am and wielding the sign until 1 pm, when Liz takes over.

Liz is 38 years old, an unemployed caregiver with rust-red hair and a wide, honest face. Her sign advertises "THREE BAD TEETH NEED PULLING. GOD BLESS," and when she smiles, her decaying dentalwork is evident.

"I work 1 'til dark," she says, long enough to make about $20 before she heads home to a backyard tent near Northeast 60th Avenue, which she shares with her old man, a sometime automotive jobber. Her presence secures the corner until Sheppard returns and the cycle repeats itself, seven days a week.

Location is crucial, but timing is also important. Liz's most lucrative hours are between 2 and 4 pm. Rush-hour commuters, with the memory of the daily grind still fresh in their heads, are actually less inclined to offer a handout.

The cartel's third member is a drug user named Shawn Lewis, 28, a burly, ruddy-faced glassblower who hangs around the corner with Sheppard. Lewis says he's been unemployed since someone stole his blowing equipment.

"It just kind of happens, you know," he exhales, cigarette smoke and cold breath condensing in the morning air. "One day you find yourself out on the streets. It's a very humbling experience."

Lewis attributes his situation to "poor decisions I've made." Among these is his battle with narcotics, which he first tried 10 years ago. Nowadays, he just wants to get on a methadone program, and wean himself from heroin.

"I got all my blood work and paperwork done," he says, with a trace of pride. "Tomorrow, I'll be able to start."

Apart from the omnipresent "God Bless," the content of the sign doesn't seem to matter much.

"You can stand here with a blank sign," laughs Tattoo Face, a.k.a. 19-year old Jason Gibson. "They know you need money."

Raised in foster homes, Gibson hit the streets of Southern California at the age of 14 and has traveled the country making up to "hundreds of dollars" in a day.

With such plunder ripe for the taking, Rose City signers ruthlessly guard their territory.

Ron, a tall, spare man with a striking white moustache and a thin ponytail, flags the eastbound approach to the Ross Island Bridge, off Southwest Kelly Street, where vehicles line up single-file before lurching out onto U.S. 26 and crossing the river. The intersection features a narrow sidewalk and waist-high guardrail—making it a perfect place for a savvy signer to dip into the revenue stream.

"I'm homeless. I live under this bridge," says Ron, 55, his rat-bitten fingers clutching a sign reading, "PLEASE HELP. THANK YOU. GOD BLESS."

A former dishwasher at Kelly's Olympian, Ron has spent the past nine years flagging at this location, pulling in $40 to $50 a day. He struggles with heroin addiction. "I've been doing dope for 42 years," he states, flashing his trademark smile.

Moments later, he clarifies his position. "I ain't using drugs," he explains, "I'm on methadone."

Despite his long tenure, Ron says he pays $15 a day—or else—to "rent" his spot from another signer he calls Shorty.

"I get real short of breath," Ron explains, referring to his emphysema. "I don't fight anyone."

Shorty turns out to be a stocky, grizzled 55-year-old Vietnam vet named Fred, who chose not to give a last name, citing an out-of-state warrant for his arrest. His record includes manslaughter, theft, criminal trespass, and 11 separate convictions for possession or manufacture and delivery of a controlled substance.

Fred usually works an adjacent median on the Barbur Boulevard ramp and adamantly denies charging Ron rent.

"Shit!" he says, incredulously. "I think he's beyond telling the truth. When his lips are moving, he's lying."

Still, Fred says Ron qualifies for disability, rents a place with friends and "shouldn't be taking other people's places who don't have anything." Fred's warrant prohibits him from collecting Supplemental Security Income assistance from Social Security, so he flies a sign reading "HOMELESS VETERAN" and sometimes makes over $70 a day. He doesn't always spend it on himself.

"I gave out 50 gifts over Christmas," he beams, indicating the small ceramic statuettes he gave his regulars, accompanied by handwritten cards. His favorite customer, "an older lady," received one that read, "Your kindness will not be forgotten. You have many times made my day with your pretty smile."

"These people have become my family," he says, his fingers absently rolling a cigarette.

Once upon a time, Fred had another family. Now they exist only as dog-eared pictures carried in his wallet: He is a smooth-faced kid, surrounded by buddies in olive-drab T-shirts and dog tags. He is a serious young man in a crisp dress uniform, shoulder to shoulder with a proud-faced father on a long-forgotten afternoon.

"I spent most of my life fucked up," he says, firing up his smoke and slipping his pictures back into the safety of their plastic pocket. "This sign thing has allowed me to become more stable. I'm about halfway to being a productive member of society."

Fred says he suffers post-traumatic shock disorder, stemming from his experiences in Vietnam, where he served three tours of duty in the U.S. Army's 9th Infantry between 1967 and 1970 and earned two Purple Hearts. But a dishonorable discharge, received after his final tour, means he doesn't qualify for benefits.

"I flipped out while I was over there," he explains.

It's a dull, overcast day, and Fred is at home: a lonely mattress under the Kelly Street onramp. Guarded by massive concrete beams, the camp is a jumble of musty clothing and discarded sleeping bags. The damp, dirt floor is littered with newspapers, food wrappers, cigarette butts and rat shit. The acrid tinge of urine hangs in the dead air.

"They say, 'Get a life,'" he mumbles, a freshly spent needle resting near his arm, his glassy eyes cast up into the gloom, where traffic rumbles a few feet overhead. "This is my life."

Flaggers trade on hope—the hope that one more dollar will buy a meal, a motel room, a bus ticket, something to get them on their feet. Unfortunately, it didn't work that way for Paul Jacobs.

Jacobs, 44, flagged for 10 years. Between 1999 and 2003, police cited him for "solicitation on or near a highway" eight separate times, despite the fact the Oregon Court of Appeals had ruled the law unconstitutional in 1996.

"I spent damn near two years in jail," he says, bitterly.

Eventually, Jacobs contacted the Oregon Law Center and sued the City of Portland for violating his free speech. The city settled out of court last September and paid Jacobs $10,000 plus $9,500 in legal fees.

"Yeah, I got a $20,000 settlement," he gripes. "Then a hospital sued me and took seven grand. The lawyers took 10. I ended up with $3,000."

Jacobs believes press coverage worked against him. "Everybody saw my picture and thought I had 20 grand in my bag. I couldn't make a dime flying a fucking sign for three months." He says the only thing he gained is the 1986 Dodge van he lives in.

Jacobs also says media coverage cost him his job at Wild Bill's Interactive Events on Northwest Vaughn Street, though, truth be known, he owes The Oregonian a debt of gratitude for getting him the job in the first place.

Owner Rick Walker read about Jacobs' settlement in the daily and happened to notice him flagging nearby.

"I went out and approached him," says Walker, who offered Jacobs a job holding a sign advertising high-end poker supplies. "I think he was out there for two days," Walker chuckles. "Then he just disappeared."

These days, Jacobs is a self-employed signer, usually working the corner of Northeast 39th Avenue and Sandy Boulevard.

"I made about six bucks since noon," he spits, shaking his head and scratching his thick, gray beard. Just then, a silver Volvo wagon pulls up with a Ted Nugent decal on the front window and all manner of archery equipment stuffed in the rear.

"How long you been standing here today?" asks the driver, a man in his late 30s.

"About two hours," answers Jacobs.

"I wish I could stand still for two hours!" Volvo-man sneers.

"Ain't you got a dog to kick around, or a wife to beat?" Jacobs replies.

"No," taunts the driver, as the light turns green. "You'll do."

What is it about flagging that drives people crazy?

"It creates an environment that is uncomfortable, disturbing, sad and appalling," says Hollywood Boosters Chairman Patrick Donaldson, whose group is concerned about the negative impact flaggers exert on the Hollywood District.

"Panhandling evokes an enormous amount of emotion on both sides," says Molly Neck, program director of the National Coalition of the Homeless. "There's a belief that people are homeless by choice, or due to mistakes they've made. It's like, 'I have a job, why can't you?'"

The reasons are anything but simple. Many signers face obstacles to employment such as homelessness, criminal background, substance abuse or mental illness. When you have no phone, no shower and no washing machine, finding a job is tough—and signing starts to make sense.

Organizations like the NCH encourage donors to give their spare change to charities and programs designed to help people off the streets. But whether you give money to panhandlers or not, Neck says, "You should treat them with dignity."

Perhaps it's the sneaking suspicion that the signs are half-truths—or outright fabrications—that infuriates so many motorists.

"We all lie a little bit," says Mike, 45, a recovering alcoholic and multiple-sclerosis sufferer who favors a traffic island near Northwest 16th Avenue and Couch Street. "I've used 'Homeless Christian,' 'Homeless Veteran,' 'Tough Times' and "Brother can you spare a dime?'"

"I've seen women stuffing their maternity dresses," he adds, clutching his current sign—"NEED TO GET OREGON I.D., ANYTHING WOULD HELP."

Some dishonest flaggers have made life more difficult for their more deserving comrades. Tom Carney, who manages the restaurant Old Wives' Tales near the popular East Burnside and Sandy corner, says the signers have worn out their welcome.

"We were trying to be gracious, let them use our bathroom and give them water," says Carney. "Then one guy came in and grabbed a few bucks off the counter."

Carney chased him down and took the money back. Now, says Carney, no one from the intersection is welcome.

Out on the median, I'm not feeling too welcome myself. After another 30 minutes, I'm cold, stiff and smelly—and, though I dare not count my money in plain sight, I'm also richer by $10.17, a tuna fish sandwich and a can of Miller Lite.

Across the street, through a string of cars speeding through the intersection to beat the yellow light, I see Scab Nose lurching toward me. The look on his face leaves little room for question: My shift is finished. I fold my sign and head for my truck.

On one hand, it's pathetic that anyone would be willing to scrap over such a meager haul. But for many flaggers, their turf is their livelihood, the only thing they have—and they'll fight to protect it. And though no one claims to enjoy flagging, some have convinced themselves that they are actually performing a civic duty.

"I try to make people happy," says Ron, a lucid smile hanging across his leathery face, his eyes heavily lidded. "I'm going to heaven."

Then he turns back to the late-afternoon traffic filing onto the Ross Island Bridge like a string of thoughtless ants.

Want to help the homeless? Consider donating to these worthy causes:

Outside In 1132 SW 13th Ave., 535-3800, www.outsidein.org

Sisters of the Road 133 NW 6th Ave., 222-5694, www.sistersoftheroad.org

JOIN 3338 SE 17th Ave., 232-2031, www.joinpdx.com

Oregon Food Bank 7900 NE 33rd Drive, 282-0555, www.oregonfoodbank.org

"Whenever I see a homeless guy, I always run back and give him money, because I think, 'Oh my God, what if that was Jesus?'" —Pamela Anderson in TV Guide.

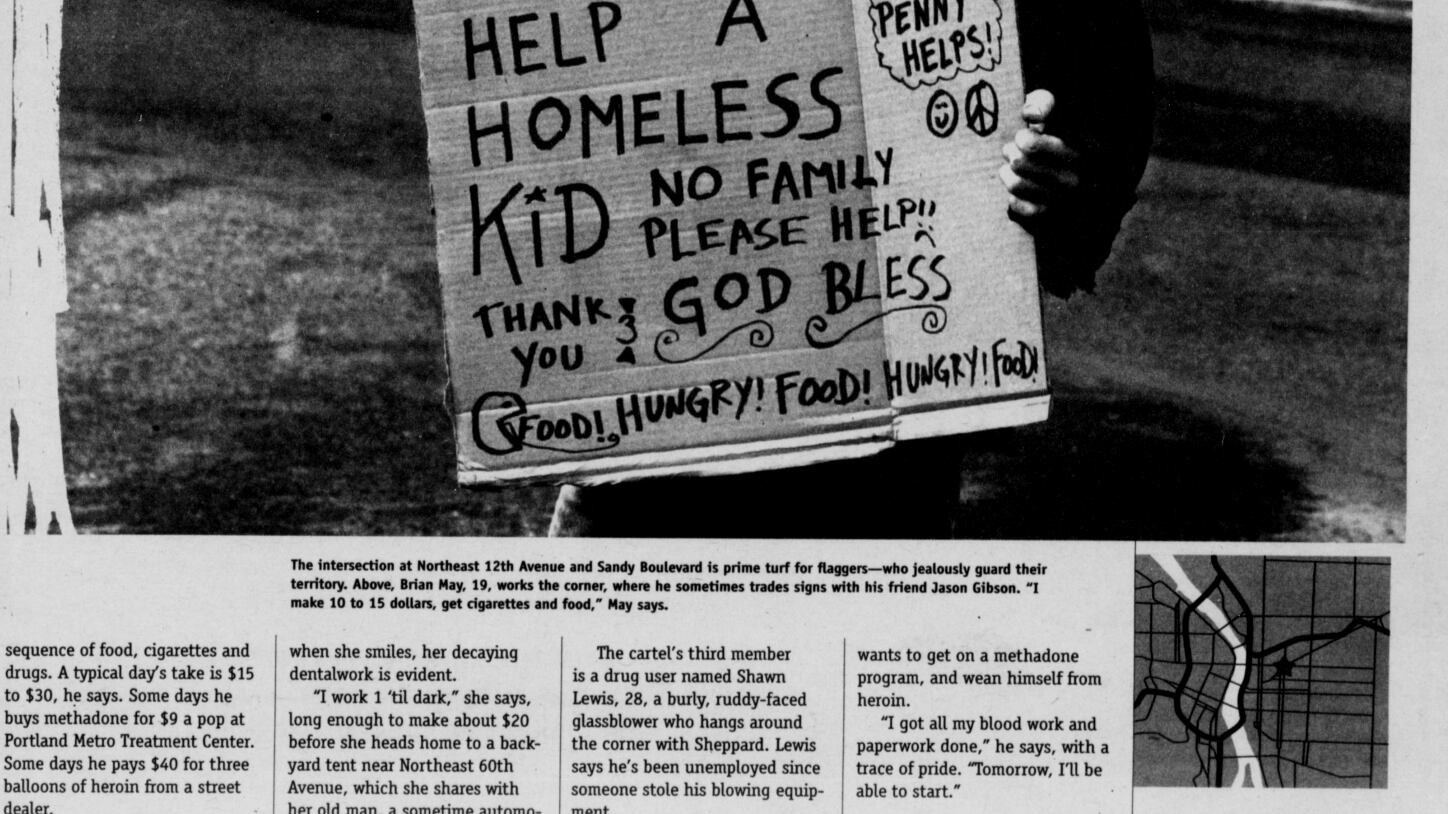

WW's unscientific tally of local flaggers included spot inspections at Northeast 12th Avenue, Lloyd Center, the Rose Quarter, Northeast 39th Avenue and Sandy Boulevard, 58th Avenue, Interstates 5, 205 and 405, OR 217, U.S. 26, and around the Hawthorne, Ross Island and Fremont Bridges.

WW reporter Fitzpatrick donated his $10.17 panhandling spoils to Outside In. He drank the Miller.

WWeek 2015