Sponsored Content Presented by Portland Art Museum

In 1889, a group of young avant-garde painters formed a brotherhood to reinvigorate French art. They called themselves the “Nabis,” derived from the Hebrew word for prophets. They met as students at the Académie Julian, an art school in Paris, where they chafed against the traditional education of the time. Instead, they were inspired by Paul Gauguin’s daring use of color and symbolism that went beyond the lessons of Impressionism.

Building on that foundation, the Nabis created a highly personal art. There was no one prescribed style: Each artist pursued his own vision, but the inspiration and encouragement flowed freely among the artists. When viewed together, they formed a cohesive expression marked by bright, intense hues and small, penetrating scenes of everyday life.

Portland Art Museum’s exhibition Private Lives: Home and Family in the Art of the Nabis, 1889–1900, on view through January 23, 2022, explores the intimate interiors, gardens, and family life of four of the artists in the collective—Pierre Bonnard, Édouard Vuillard, Maurice Denis, and Félix Vallotton. These artists and friends focused on what Bonnard called “modest acts of life”—tiny, quotidian moments that can hold great meaning, memory, and emotion.

Their shared interests—and, in the case of Bonnard, Denis, and Vuillard, a shared studio space —brought these men together to explore similar themes of family and the pleasures and complications of both familial and romantic relationships.

Félix Vallotton drew inspiration from the precision and beauty of Japanese woodcut prints, which spoke to the Swiss-born artist’s meticulous nature, as seen in his hyperrealistic early portraits and in the detailed journals he kept throughout his life.

Once he connected with the Nabis, Vallotton’s paintings became more abstract and rich with color, which let the sharper elements tell a more detailed story. The Lie, featured in PAM’s Private Lives, for example, shows a couple in what appears to be a romantic embrace, but the expression on the man’s face is ambiguous: Does it register desire, pain, or disgust? The title,

too, suggests that this isn’t an idyllic romance, but Vallotton offers us few clues to the unfolding drama. It’s a devastating painting, despite its humble size: a mere 10 by 13 inches.

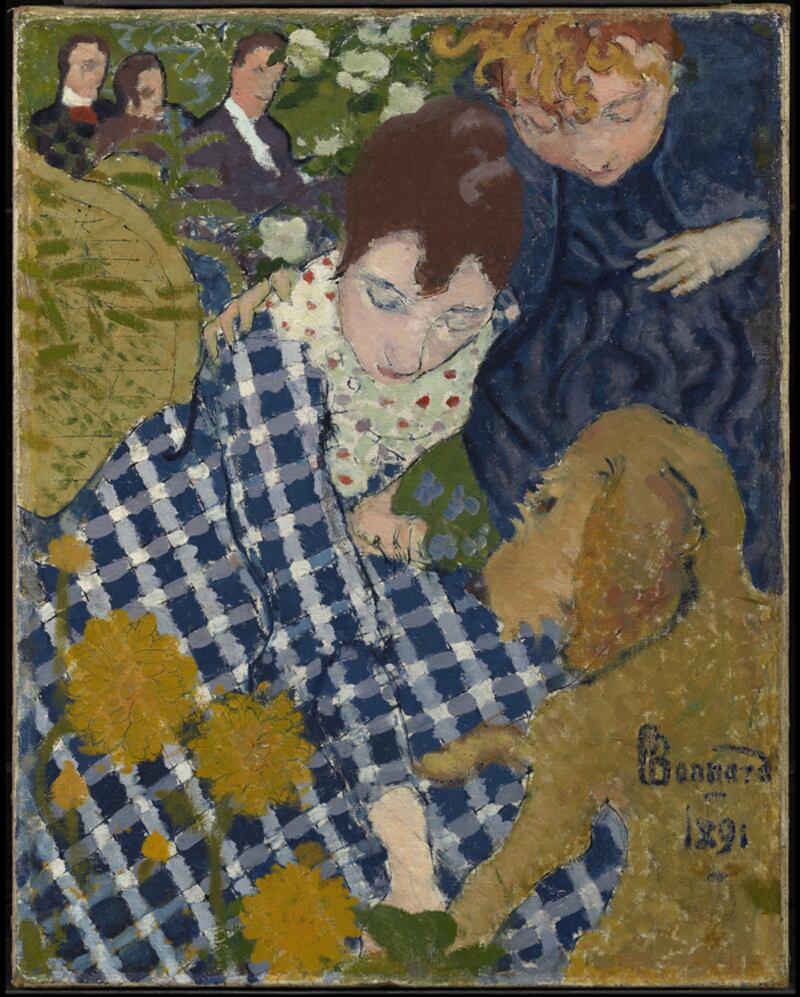

Pierre Bonnard was also sparked by the work of Japanese printmakers, earning him the nickname “the very Japanese Nabi.” He incorporated flattened forms, unusual perspective, and rhythmic patterns to evoke emotion in the viewer. Quiet by nature, he nonetheless overcame familial objections to pursue a life as a painter; his father insisted that he also earn a law degree, but ultimately accepted Bonnard’s choice.

A touch of melancholy burnishes the edges of his early masterpiece, Women with a Dog, a striking depiction of his sister, Andrée, cousin Berthe, and the family dog Ravageau. Bonnard was apparently in love with Berthe, even proposing marriage, but she turned him down. The physical proximity of the three main figures suggests their kinship, while the garden setting evokes the Bonnard family home in rural France where they gathered every summer.

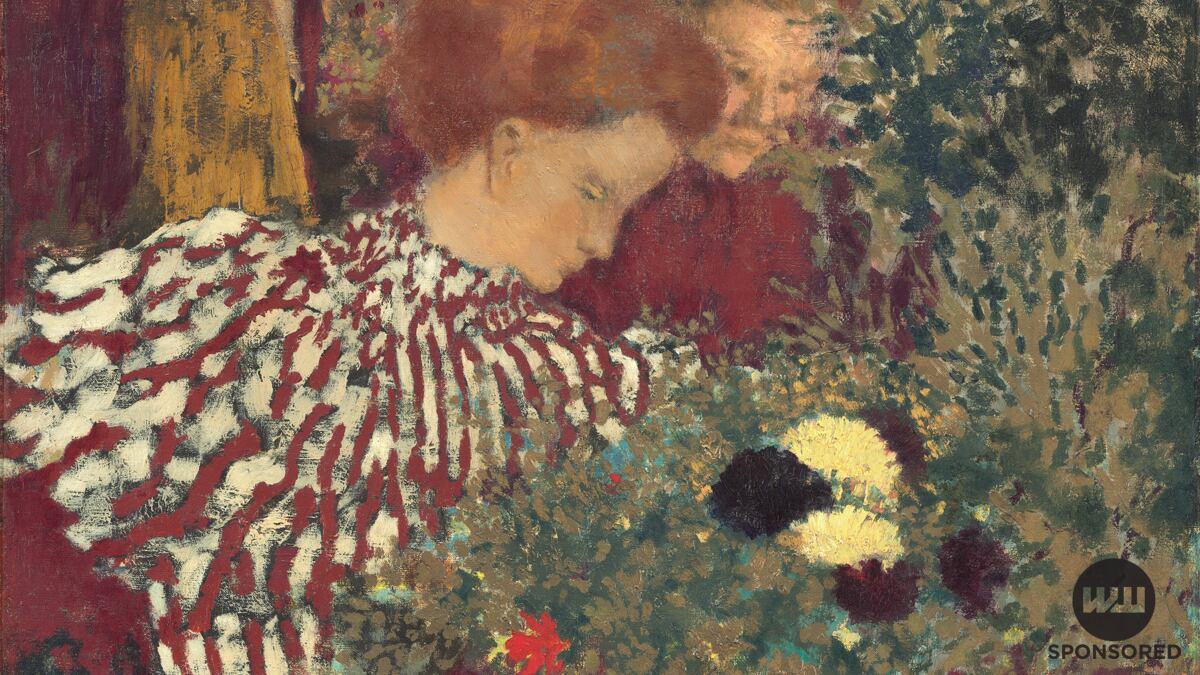

Women were central to much of Édouard Vuillard’s work and life. He lived with his mother until her death when the artist was in his 60s, and he famously claimed that “Mother is my muse.” She ran a dress- and corset-making business from their shared apartment, and Vuillard was highly attentive to the patterns, fabrics, and other textiles that she plied for her trade. Rich color and texture mark his work, as in Woman in a Striped Dress, one of the highlights of the exhibition. Vuillard’s flickering brushwork suggests the glow of gaslight in this cozy interior, bathed in shades of red and white.

Maurice Denis was the theoretician of the Nabi group. In a groundbreaking essay in the journal Art et Critique, he insisted that “the profoundness of our emotions comes from the sufficiency of these lines and these colors to explain themselves. Everything is contained in the beauty of the work.” In other words, color and line could do more than describe shapes—they could evoke emotion, suggest feeling, and create an inner, symbolic world.

This modernist approach is evident in Denis’s painting of this period. Often using one of his nine children, or his wife, Marthe Meurier, as his models, Denis found inspiration in simple domestic scenes such as Washing The Baby. The gentle task on display perfectly evokes the deep bond between mother and child, even as it speaks to the joy of discovery as the infant explores her toes. The ordinary subject is enlivened by the undulating forms of Marthe’s dress. Moreover, the sophisticated composition echoes the balance and dexterity needed for this common chore.

It is ironic that these young artists, who sought to radically transform the art world, chose such modest subjects for their work. Vuillard once remarked that it was only the people, places, and objects closest to him that could spark artistic inspiration. By focusing on intimate interiors, close family and friends, and even the family pets, these artists created a quietly radical art that draws viewers in, suggests an unspoken narrative, and dazzles the eye.

Private Lives: Home and Family in the Art of the Nabis, 1889–1900 is on view at the Portland Art Museum from Oct. 23, 2021, through Jan. 23, 2022. Learn more and plan your visit.