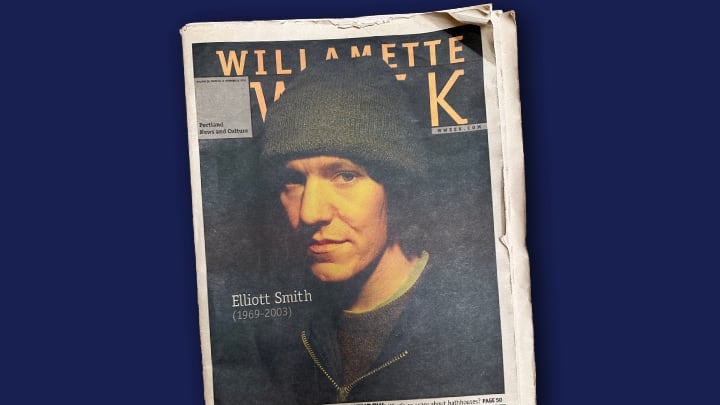

On Oct. 21, 2003, Elliott Smith died in Los Angeles. The following Wednesday, WW published a cover package that attempted to make sense of losing Portland’s defining musical icon. Twenty years later, what stands out in the coverage is both the rawness of the wound Smith left in those who loved him, and the enduring power of his songwriting as a key to unlocking the soul of this city.

These stories first ran in the Oct. 29, 2003, edition of WW.

A city is lucky to have a musical icon. An artist who, for a brief time, embodies the unique urban history of a place, while adding chapters to that history. New York had Lou Reed in the 1960s, Detroit had Iggy Pop in the early 1970s, Seattle had Kurt Cobain in the early 1990s. And up until last week, Portland had Elliott Smith.

For some Portlanders, Smith’s name might recall a simple, beautiful song from a sentimental film some years back. To others, Smith’s tales about living on the margins of misery captured the city’s dark side, while his gritty realism delivered beauty, too. Even though the musician left Portland five years ago, each song he has written since contains a new piece of history for our town.

That all ended Tuesday, Oct. 21, when Smith died at a Los Angeles hospital from an apparently self-inflicted knife wound. And while it’s easy to hear the despair in the singer’s lyrics, Elliott Smith’s life—and music—can’t be judged only by its ending. In the early days, his musical career resembled that of any number of young, promising indie artists. After playing a variety of instruments as a child, Smith picked up the guitar in high school. He later formed a band with college friend Neil Gust, and their group, Heatmiser, would go on to release three full-length albums.

Along the way, Smith began writing his own songs. In the mid-1990s, he released three solo albums of spare acoustic songs. Those albums earned the singer a devoted local following, but outside of the post-grunge Pacific Northwest, his success was modest.

Everything changed when Portland filmmaker Gus Van Sant featured six of Smith’s songs on the soundtrack to the film Good Will Hunting. Suddenly, the disheveled singer had an audience of millions. Soon after, he signed to a major label, then moved, first to New York and then to Los Angeles.

Articles in magazines such as Rolling Stone, Magnet and Under the Radar probed the singer’s life, attempting to uncover the personal depression and addiction that informed his songs. Smith became the tortured troubadour of the century’s end, a kindred soul to Nick Drake, the melancholic 1970s folk singer and fellow suicide victim.

His musical output slowed in the past few years, but at the time of his death last week, he was working on his sixth full-length release, tentatively titled From a Basement on the Hill.

L.A. may have been where the musician’s life came to its sudden end, but Portland is where Smith spent his formative years. As his songs retain the stamp of the city, Portland retains Smith’s imprint. WW asked friends, family, colleagues and fans to share impressions of the young songwriter with the quiet sound. Listening to their voices offers some help in coming to understand a musician—and a man—who never quite understood how to live. —Mark Baumgarten

“Just let me fall out the window with confetti in my hair.”

—Elliott Smith quoting Tom Waits in the 1987 Lincoln High School yearbook, in a section titled ‘Final Words—Seniors Say Goodbye.’

No, I shouldn’t have won [the Oscar].... If I won it, I would put it in my closet! But Celine [Dion] will put it on her mantelpiece.... You liked the suit? There was a suit I could never afford. This is as good as it looks, right here.”

—Elliott Smith on his Oscars performance, speaking on stage at LaLuna, Portland, May 16, 1998

“I don’t really know what happens when you die. I don’t like the idea of being buried. I would prefer to walk out into the desert and be eaten by birds….”

—Elliott Smith, in a 2001 Magnet magazine interview

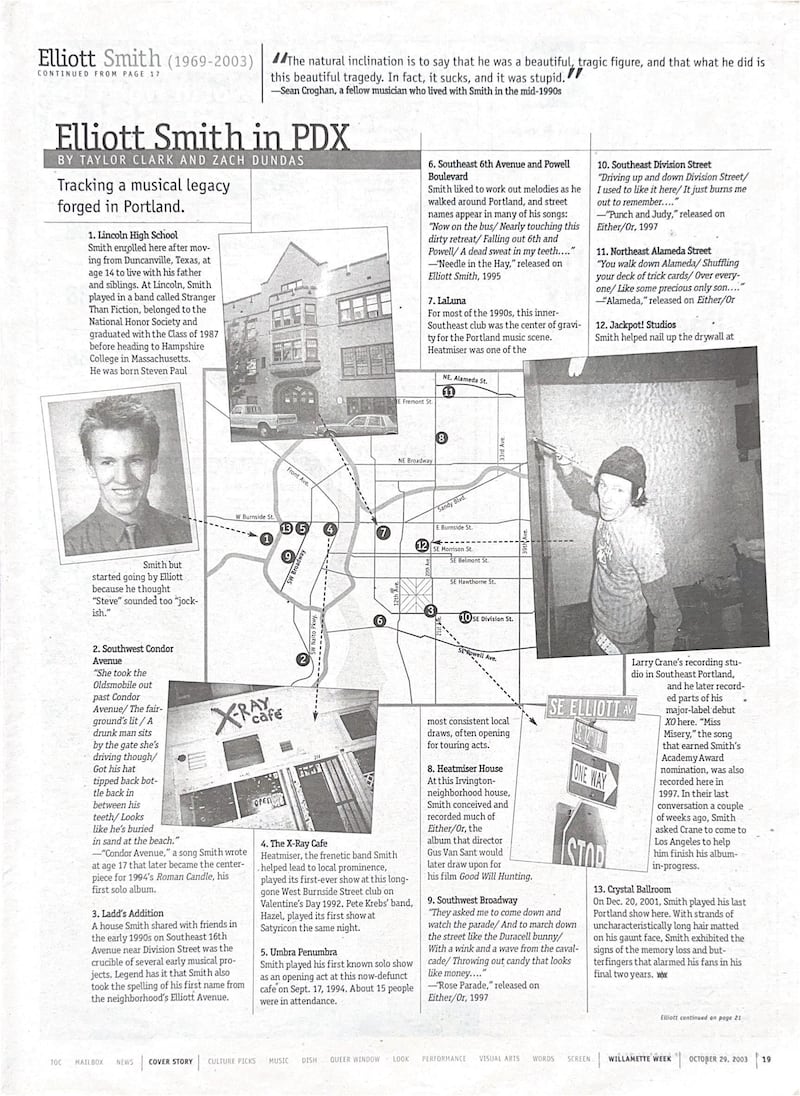

Elliott Smith in PDX

Tracking a musical legacy forged in Portland.

By Taylor Clark and Zach Dundas

1. Lincoln High School

Smith enrolled here after moving from Duncanville, Texas, at age 14 to live with his father and siblings. At Lincoln, Smith played in a band called Stranger Than Fiction, belonged to the National Honor Society and graduated with the Class of 1987 before heading to Hampshire College in Massachusetts. He was born Steven Paul Smith but started going by Elliott because he thought “Steve” sounded too “jockish.”

2. Southwest Condor Avenue

“She took the Oldsmobile out past Condor Avenue/ The fairground’s lit/ A drunk man sits by the gate she’s driving though/ Got his hat tipped back bottle back in between his teeth/ Looks like he’s buried in sand at the beach.”

—”Condor Avenue,” a song Smith wrote at age 17 that later became the centerpiece for 1994′s Roman Candle, his first solo album

3. Ladd’s Addition

A house Smith shared with friends in the early 1990s on Southeast 16th Avenue near Division Street was the crucible of several early musical projects. Legend has it that Smith also took the spelling of his first name from the neighborhood’s Elliott Avenue.

4. The X-Ray Cafe

Heatmiser, the frenetic band Smith helped lead to local prominence, played its first-ever show at this long-gone West Burnside Street club on Valentine’s Day 1992. Pete Krebs’ band, Hazel, played its first show at Satyricon the same night.

5. Umbra Penumbra

Smith played his first known solo show as an opening act at this now-defunct cafe on Sept. 17, 1994. About 15 people were in attendance.

6. Southeast 6th Avenue and Powell Boulevard

Smith liked to work out melodies as he walked around Portland, and street names appear in many of his songs:

“Now on the bus/ Nearly touching this dirty retreat/ Falling out 6th and Powell/ A dead sweat in my teeth....” —“Needle in the Hay,” released on Elliott Smith, 1995

7. LaLuna

For most of the 1990s, this inner-Southeast club was the center of gravity for the Portland music scene. Heatmiser was one of the most consistent local draws, often opening for touring acts.

8. Heatmiser House

At this Irvington neighborhood house, Smith conceived and recorded much of Either/Or, the album that director Gus Van Sant would later draw upon for his film Good Will Hunting.

9. Southwest Broadway

“They asked me to come down and watch the parade/ And to march down the street like the Duracell bunny/ With a wink and a wave from the cavalcade/ Throwing out candy that looks like money....” —“Rose Parade,” released on Either/Or, 1997

10. Southeast Division Street

“Driving up and down Division Street/I used to like it here/ It just bums me out to remember....” —”Punch and Judy,” released on Either/Or, 1997

11. Northeast Alameda Street

“You walk down Alameda/ Shuffling your deck of trick cards/ Over everyone/Like some precious only son....” —“Alameda,” released on Either/Or, 1997

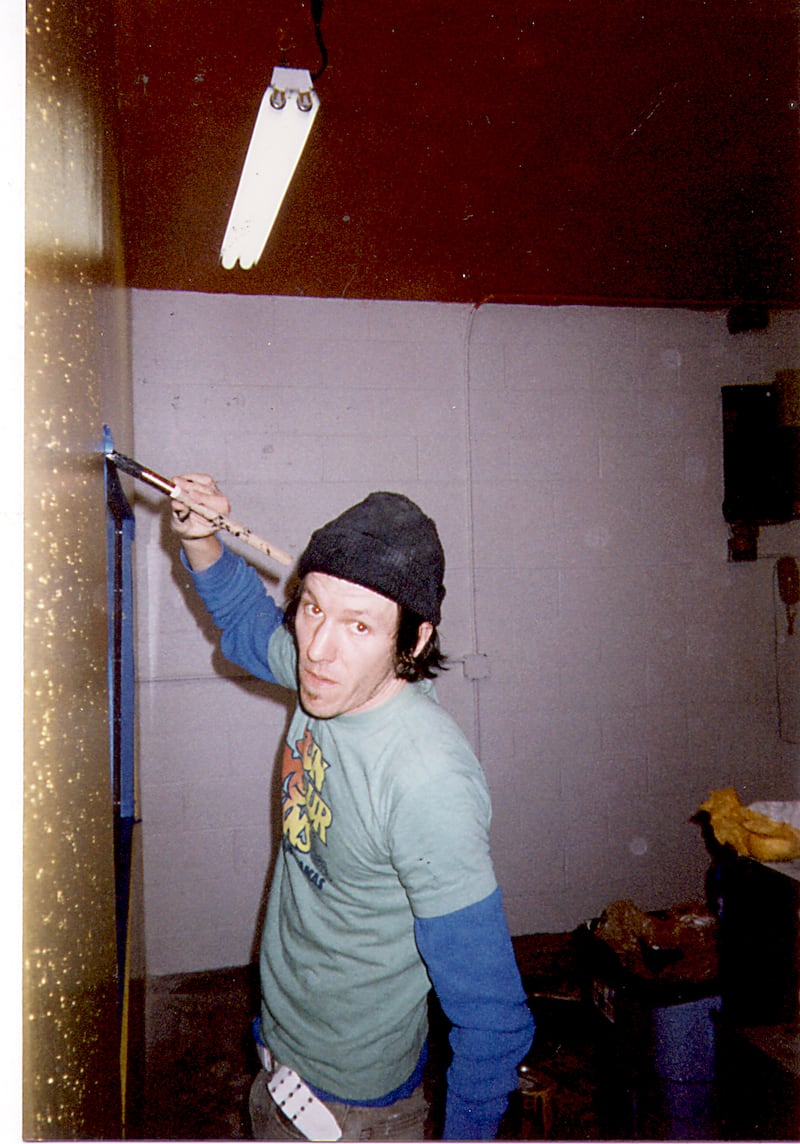

12. Jackpot! Studios

Smith helped nail up the drywall at Larry Crane’s recording studio in Southeast Portland, and he later recorded parts of his major-label debut XO here. “Miss Misery,” the song that earned Smith’s Academy Award nomination, was also recorded here in 1997. In their last conversation a couple of weeks ago, Smith asked Crane to come to Los Angeles to help him finish his album-in-progress.

13. Crystal Ballroom

On Dec. 20, 2001, Smith played his last Portland show here. With strands of uncharacteristically long hair matted on his gaunt face, Smith exhibited the signs of the memory loss and butterfingers that alarmed his fans in his final two years.

Errant Son

Elliott Smith and Portland walked hand in hand.

By John Graham

Five years ago, just at the moment when Elliott Smith traded his status as a local cult icon for that of a national indie-rock darling, the documentary Strange Parallel was released. The 35-minute film—by Beck video director Steven Hanft—follows Smith around his (then) new neighborhood in New York City, adds some live-performance clips and inserts parodic, faux-commercial footage about some sort of robotic hand device.

The film does Elliott Smith wrong. All wrong.

The one thing that Strange Parallel—and often the entire national media—missed about Elliott Smith is the one thing residents of this city can claim as their shared yet secret understanding: Portland played a crucial role in the musician’s development as an artist.

Portland was where he rode out the turbulent waves of adolescence. Portland was where he suffered the internal, invisible traumas of the shy and poetically inclined. Portland was where he persevered and grew into a distinctive and instinctual musician. And Portland was where he built a regional cult following that supported him almost religiously until the end.

Though it may sound like an absurd overstatement, in some ways Elliott Smith is artistic Portland. Or at least a fine representation of and avatar for it. Literate. Stormy. Tormented. Prone to grandiose ambitions but weighted down by shame and insecurities.

Elliott’s early solo albums are like cheat sheets for comprehending every Rose City songwriter who ever wrestled with a four-track recorder in his or her bedroom: fighting the guitar for that elusive transitional bridge chord. Trying to decipher lyrics scribbled onto a bar napkin at last call. Whispering into the microphone so as not to wake the housemates.

It was these confessional tales, on Roman Candle, Elliott Smith and Either/Or, which made him such an adored figure around town. There was something about the solo albums—so private and yet strident at the same time—that hit some kind of Portland indie-rock G-spot. Witnessing the odd symbiosis that occurred between Elliott and his audiences during those early shows was like being privy to a cerebral orgy.

Here was this decidedly unattractive fellow (the opposite of, say, Dashboard Confessional’s Chris Carrabba) floating his innermost fears and romantic devastations into the crying wind, and the local Zeitgeist sucked it down greedily. Did it make you feel dirty to be such an emotional voyeur? Hell, yes. At a time when Pacific Northwest grunge mania was finally dying out, however, Elliott Smith’s brand of miniaturized psychodrama seemed the ideal balm for a regional music scene that felt as if it had just been raped.

And, of course, there are the lyrics that seemed as if Smith had ghostwritten them from within your own psyche.

Look for telltale metaphors and images that link up to shared Portland experiences. Like: “They’re waking you up to close the bar/ The street’s wet, you can tell by the sound of the cars,” from the song “Clementine.” To be sure, it’s a scene with which almost every rain- and beer-marinated Portlander can identify. Same goes, for that matter, for the entirety of the song “Rose Parade.”

More elusive are the lyrics expressing the state of mind closest to the cloudy, shrouded melancholia that so often hangs like a pall above our city’s skyline. You know the feeling—it infuses the air with an oily poison on those days when you haven’t seen the sun for a month and you can’t imagine what it will feel like when it returns.

Elliott rapidly ascended from playing small, unassuming gigs at coffee shops like Umbra Penumbra to upstaging local favorite and friend Pete Krebs at the (then pre-lesbian) Egyptian Room.

Suddenly there were shows like the Satyricon gig with Cat Power. Rarely was an audience compelled to sit, cross-legged, on the filthy tiles of that scabrous punk-rock dive and act like polite, silent and reverent schoolchildren. But they did just that as Elliott poured himself out into the hushed atmosphere; it was then you realized Elliott Smith couid be huge. And not just in Portland. He had a kind of magnetism that quietly worked its black magic ways.

Then came Gus Van Sant. Good Will Hunting. And the insane surrealism of seeing poor, pimply, slouched Elliott Smith share an Oscar stage with chrome-plated power-diva Celine Dion. After that, everyone in Portland knew Elliott would stray. A jump to DreamWorks, a major label. Moves to New York, then Los Angeles. See ya. Ancient history.

Still, Elliott never forgot Portland. He’d often return to visit friends like Sam Coomes or Larry Crane. He even spent some of his DreamWorks advance money on a giant vintage mixing board for Crane’s Jackpot! Studios. Sometimes you’d randomly catch him slumping across the threshold of favorite haunts like My Father’s Place, familiar as old times and more bashful than ever.

And Portland certainly never forgot Elliott. Even if he never consciously represented the city, he’d been elected to the role. Hell, he fit the role better than most of his own clothes fit him.

So, how to remember Elliott Smith, Portlander? Obviously, the albums remain. And if you want a visual key to unlock those memories, steer clear of Strange Parallel. Instead, seek out the short film Lucky Three by Jem Cohen (of Fugazi’s Instrument fame). In 11 short minutes—enough time for three Smith songs—you will see shots of Elliott crumpled behind a beat guitar and microphone, as always.

And interspersed throughout are snapshots of the city we all know: the skyline swimming in rain clouds, puddles waiting for the sun, streets patient and gray and possessed by a faint, wraithlike sense of both hope and desperation.

In other words: Portland. In other words: Elliott Smith. In other words: one and the same.

An Oral History

Friends and collaborators remember Elliott Smith.

“The natural inclination is to say that he was a beautiful, tragic figure, and that what he did is this beautiful tragedy. In fact, it sucks, and it was stupid.” —Sean Croghan, a fellow musician who lived with Smith in the mid-1990s

“In Portland, a lot of people were very forgiving of Elliott’s problems but got pushed to the point where we couldn’t forgive anymore. It sounds terrible, but we had to say, ‘If you’re going to kill yourself, fucking do it. Don’t keep talking about it.’” —Pete Krebs, formerly of the band Hazel a musical collaborator and close friend of Smith’s

“My memory of Elliott isn’t of a stupid junkie shadow of his former self. It wasn’t the guy who died yesterday. I remember the guy who was always cracking jokes.” —Pete Krebs

“He was very sensitive. He was one of those bright, animated, thoughtful kids that you liked having in class.” —David Bailey, Smith’s civics teacher at Lincoln High School

“He was an amazing guy to watch and work with, because the songs were always fully formed in his head when he came to the studio. I’ve seen very few people like that. He really didn’t need a producer or an engineer, because he knew exactly how he wanted it all to fit together. It was fun to watch—he’d lay down a drum track, and I’d be like, where is that going to go? But he would pull it together.” —Larry Crane, owner of Jackpot! Studios, who recorded Smith

“It would be fair to say that his desire to hurt, injure or destroy himself was indomitable. To say that his death was somehow inevitable would be a way that people who watched him die over many years attempt to comfort themselves.” —Gerrick Duckler, Smith’s close friend and former bandmate in Stranger Than Fiction

“Even when it was going better for him, it was going bad. Elliott’s good was most people’s worst nightmare.” —Fellow musician and former housemate Sean Croghan

“On the occasions when I met him, I was struck by how fragile he seemed. Unlike most performers, there really didn’t seem to be a difference between onstage Elliott and offstage Elliott. The performing persona and his real personality were one and the same.” —Charles R. Cross, Seattle music writer and former editor of The Rocket

“[Roman Candle], really, was the only album he ever made with no expectation that anyone would hear it. He made it with a pot of coffee and a fourtrack, sitting at his kitchen table, just to get it out.” —Christopher Cooper, of the Portland label Cavity Search

“You wouldn’t think that he cared about his appearance from the clothes that he wore, but he would sometimes try on outfits for half an hour to get to the right combination of faded cords, T-shirt and baseball cap.” —Andrea Manning, a close friend and roommate of Smith’s in the early 1990s

“As roommates, we were a great match if you like to be depressed all the time—drink too much, smoke too many cigarettes and take pills occasionally. It was perfect. It seemed like he was addicted to being sad. I think he worried that if he wasn’t sad, he wouldn’t be able to write songs anymore.” —Sean Croghan

“He didn’t drink heavily in those days, at least not to my knowledge. In fact, one time I was at the old Montage on Belmont and really wanted him to come rescue me from a bad date. I called him for a ride, but he was really concerned about driving the half-mile because he had had a beer earlier that evening.” —Andrea Manning

“I think no one is really ready to become an icon of an idea or a symbol of an entire concept. Some people are very good at being well-known, but I don’t think anyone’s ego is that big. And Elliott really became that for some people.” —Slim Moon, owner of Olympia’s Kill Rock Stars Records, which released Elliott Smith and Either/Or

“Pretty soon, he wasn’t our little hometown hero anymore. And frankly, I liked him best in that role, and I think he liked himself best in that role. But I don’t subscribe to the idea that the machine chewed him up, or anything like that. I think he simply didn’t have the structure within himself to handle being where he was. I think he needed to be where more people really loved him. He needed to take fast escapes from fame, and he did that in a number of ways, obviously. And at the brink of his quote-unquote comeback, he took the big escape.

“He almost shunned the stardom. I was with him many times when people recognized him, and he never got used to it or really liked it. He never settled into the fame, which ultimately fed into his sadness.” —Christopher Cooper of the Portland label Cavity Search, which released Smith’s Roman Candle in 1994

“He was very up front about his alcohol issues when he would do interviews, and I always admired that about him. But then, we’d be doing those interviews in a bar, more often than not. And after he moved to New York, I think every interview we did was in a bar.” —Charles R. Cross

“A lot of his friends have been mourning his death for a long time. He told me about four years ago—I’m sure we were out drinking— in one of his selfish moments, ‘Well, this is probably the last time you’ll ever see me, so goodbye.’” —Sean Croghan

“Don’t buy into the romantic myths of self-destruction that are now going to grow about Elliott. I’m still tremendously fond of the man and his work, but when I last saw him, he didn’t look like himself, and there was nothing romantic about it.” —Jem Cohen, a New York filmmaker who put together Lucky Three, a brief 1996 documentary about Smith

“His depression was a fundamental part of who he was, which is not to say that he moped around. On the contrary, at times his suffering enabled him to understand the suffering of other people. At times he was able to draw upon his experience as a means of relating to others, and part of his depression enabled him to provide others with a vocabulary for talking about things they themselves didn’t understand completely. When he was depressed he felt, as he would often say, more like himself than when he was not depressed.” —Garrick Duckler

“To the rest of the world it looks like a cliché—gifted, tortured young songwriter does himself in. Well, duh. For those of us who knew him, it’s a much bigger and more complicated story. I’ve never been on this side of a cliché, I guess.” —Christopher Cooper

“I interviewed him for OPTION magazine right around the time that Either/Or came out. I think it was at My Father’s Place on Southeast Grand. We talked about philosophy and existentialism and music, then he said: ‘Mind if we play some video poker?’ I only had like three bucks on me, but we went into the next room and sat side-by-side at the machines. I quickly lost my money, and looked over to notice Elliott feeding 20s into the slot. In the time it took me to lose three bucks, he went through 80.” —Richard Martin, former WW music editor

“I think the thing he doesn’t get credit for, and in some ways the truest thing about him, is that Elliott was hilarious. He was constantly joking, cracking people up, and I think that’s really the opposite of what most people think about with him.” —Slim Moon, owner of Olympia’s Kill Rock Stars Records, which released Elliott Smith and Either/Or

“Elliott’s album Roman Candle became a favorite, and later when I was making Good Will Hunting, I had intended to use a lot of Elliott’s music, almost like sound for the movie. We showed him Good Will Hunting on tape at my house.” —Director Gus Van Sant, who used Smith’s songs for his 1997 movie Good Will Hunting

“If you saw one of the early Heatmiser shows and then saw Elliott on the Academy Awards with Celine Dion, you’d realize that this was one of the strangest leaps anyone has ever made.” —Charles R. Cross

“He knew there were a lot of people in Portland who wanted him to be here, and wanted to help him. The last time we hung out, about a year-and-a-half ago, there were four or five of us sitting there, begging him to move back. He had doctors in L.A. prescribing him handfuls of pills. He had a thousand little yes men down there—any young, aspiring rock star in L.A. would be only too happy to go out and acquire anything Elliott wanted to ingest and give it to him. He had people who wanted to help him, but he made a stupid decision, and a selfish decision. He wasn’t a sad, fragile little boy. He was a man.” —Sean Croghan

“It sounds stupid to spell it out, but Elliott’s songs are great for me in their bittersweetness; such contradictory feelings bound together in the perfect, letter-sized shapes of songs. While the tunes were beautiful, his lyrics could be ruthless. But if the lyrics lost hope, the melodies and the voice found it again. If Elliott eventually lost hope himself (and with the lousy ‘help’ of drink and drugs, I guess he did), there was something in so many of the songs that kept going past all that, and should keep going now. He did a lot of great work. That’s only one of the reasons to forgive him his trespasses.” —Jem Cohen