This story first appeared in the June 19, 2013 edition of WW.

The park rangers must have been lying in wait. Out of the corner of my eye, I see them approaching. The man is tall with a shaved head and small spectacles. With him is a dark-haired woman. They know what we’re about to do, and it’s their job to stop it.

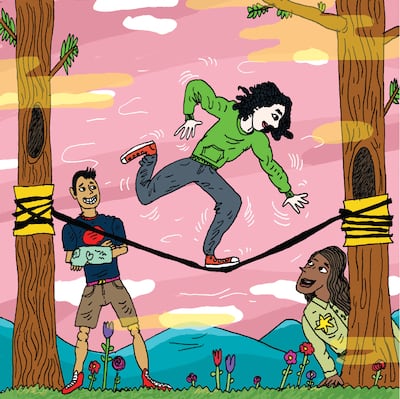

It’s an otherwise serene Sunday afternoon at Laurelhurst Park. Joggers bound along the paths, sunbathers sprawl on the grass and a group practices tai chi by the lake. I am wobbling on a 2-inch piece of webbing strung between two trees. My other arm flails above my head as I teeter, but I remain upright. Then I spot two sage green button-down shirts. Busted.

Slacklining, technically, is illegal in Portland parks. City code bans parkgoers from attaching ropes (or wires, chains or just about anything else) to trees or other structures. But that doesn’t stop slackliners from setting up in parks, albeit with some wariness. Of the four slackliners who’ve gathered at Laurelhurst Park today, most tell me they’ve been asked to take down lines, but I’ve also heard stories of slackliners attracting crowds without anyone asking them to stop. “I was here yesterday, and we had three lines set up,” says Shawn Whalen, the lanky 32-year-old snowboarding and rafting instructor encouraging me along. “Two rangers walked by and said hello.”

Whalen is also something of an arboreal evangelist, pointing out the thick padding he’s wrapped around two trees to protect their bark. He is increasingly frustrated by what he’s seen at other parks: gouged trees, fallen saplings, toppled light posts.

Derrick Peppers, a gregarious 29-year-old climbing guide, hopes slackliners avoid the aggression that characterized many early skateboard activists. “Keep breaking the law, but keep being nice about it when rangers tell you to take it down,” he says. “That’s what I always tell people.”

The rangers I spotted definitely see me. I lose my balance. They walk away.

You might recognize slacklining as an activity from Colonel Summers Park, with dreaded-out tokers traversing a rope strung between two trees. But slacklining has its roots in the rockclimbing community, where it sprung up among bored climbers in Yosemite during the ’70s and ’80s. Those climbers walked it all: chains in parking lots, climbing ropes at camp and ultimately webbing. The activity required no extra equipment and let climbers rest their weary arms while still honing their stabilizer muscles, sense of balance and mental focus. The activity remains largely limited to climbers, but in the last decade slackliners have pushed themselves to walk longer and higher lines and to execute increasingly gymnastic tricks. A slackliner performed with Madonna at the Super Bowl in 2012. A competition circuit has developed. Online videos guide slackliners through dizzying tricks and intricate footwork.

I’m not interested in competing. I’m not interested in flips, somersaults or cartwheels on the line. I just want to defy a bit of gravity and impress some friends at a picnic. So a few weeks ago, I tracked down Chloe Mandell, a high-school acquaintance and instructor at the Circuit Bouldering Gym who agreed to give me a lesson.

My first trip on the line nearly makes me seasick. As I grip Mandell’s hand, the rest of my body shakes with untamed abandon. I feel like a cartoon squirrel being electrocuted. But after that initial earthquake, I begin to find my balance. Mandell’s tips: Don’t look down. Find the line before you transfer your weight. Bend your knees. Keep your hands above your head for balance. Breathe. By the end of my first lesson, I take a few steps on my own. I go back again a few weeks later, and get better yet.

I’m not exactly in the zone on this sunny afternoon in Laurelhurst Park, but I do feel a sense of relief as the rangers walk away from us. Clambering back on, I take a few steps before tumbling to one side. In a different corner of the park, Peppers and Rob Wright, a 45-year-old math and science teacher, have strung up a massive line, nearly 7 feet off the ground and 115 feet long. A little girl watches as Wright crosses it, very carefully. “Whoa, Mom, look what they’re doing!” she squeals. “Let’s watch!” A dog-walker stops to snap a photo on his iPhone.

My relief is short-lived. The park rangers return. The man tells us to take down the lines. His tone is apologetic, almost rueful. He watches as Travis Danner, a 31-year-old engineer, walks the line. “If I wasn’t on the clock, I’d try it myself,” he says. “I’ve got pretty good balance.”

The slackliners ask if they can have another go before disassembling. The ranger’s eyes flit back and forth between their pleading faces. He gestures to his partner. “We’re gonna take a walk around the park,” he finally says.