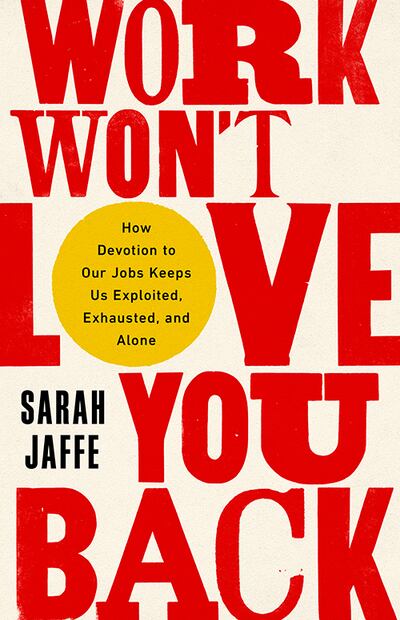

In her latest book Work Won’t Love You Back: How Devotion to Our Jobs Keeps Us Exhausted, Exploited, and Alone (Bold Type Books, 432 pages, $30), labor reporter Sarah Jaffe paints a grim portrait of late American capitalism. “It’s become especially important that we believe that the work itself is something to love,” she writes. “If we recall why we work in the first place–to pay the bills–we might wonder why we’re working so much for so little.”

In short: Your job probably doesn’t “love you,” and gratifying work hardly justifies ridiculous hours and stagnant wages. As Jaffe describes it, the industrial work ethic has morphed into a “labor of love” ethic: the fantasy that society has advanced beyond rote factory work, that capitalism in its current state allows all workers to parlay their specific interests into a career, and that flexible side hustles are worth it, even when they come at the expense of benefits or basic employee protection.

WW spoke to Jaffe about the core of her new book’s thesis, its connection to the endless controversy surrounding virtual learning in a locked-down world, appreciating print journalism as an essential community service, and more. The conversation has been condensed for readability.

WW: You offer a definition early in the book of neoliberalism, a term that gets thrown around a lot. How would you describe neoliberalism in the simplest terms, and how does it connect to your thesis that work won’t love you back?

Sarah Jaffe: A lot of people use it to just sort of mean capitalism. “Late capitalism” is another thing that people throw around as a synonym for neoliberalism. But when I’m talking about neoliberalism, I mean a sort of particular political project, with two goals. One is to destroy, once and for all, the ideals of socialism, or communism, or any sort of social solidarity that one might build a society around. And the other one is to reinscribe profit.

So to do that, neoliberalism becomes a political project, with the goals of putting the market in everything. Something like charter schools are a perfect example of a neoliberal way of thinking about education, that rather than put funding into public schools—which are an institution of solidarity, which are available in theory to everyone—we create charter schools where kids compete to get into the good schools and thereby get out of the supposedly bad public schools.

Right now with teachers, with a new COVID wave, there’s a battle yet again over whether we should force everyone back into public schools. And they keep saying that teachers are lazy and don’t want to work, when in fact, the teachers are saying, “We don’t want to give COVID to our children. And therefore, we are working. And we’re working harder because teaching virtually is actually very hard.” The language of loving your job goes hand in hand with the project of privatizing the public school, making profits for some people, and getting work for less out of the teachers who do it.

The language of loving your job seems so pervasive. There’s this phenomenon of employers trying to sweeten the deal with kombucha on tap in the break room or company retreats. And it creates this pissing contest of trying to prove your employer actually cares about you. Do you think this is ever coming from an authentic place?

I have had good bosses and bad bosses in basically every industry I’ve worked in, from journalism to waiting tables, who were genuinely lovely people, who genuinely tried to take care of us. Some of the employers who put together cool perks—kombucha on tap, Friday night happy hour on the company tab, or whatever—are genuinely trying to be nice bosses. This is particularly true in the nonprofit sector, where the boss genuinely believes in the cause. These are structural issues.

Quitting to find another job is exactly what the labor-of-love ideology tells us to do. The problem is, with capitalism, you can’t escape it. You can’t clock out of it. You can’t find a job that is somehow outside of it. Nonprofits are theoretically not for profit—however, where does the money come from? The money comes from Bill Gates and Warren Buffett and all the rest of them. Where did they make their money? How do they expect the nonprofit to be run and come up with reports and deliverables and all that bullshit?

The Italian communist Antonio Gramsci, who wrote mostly in a fascist prison, writes about common sense as something that has political material. The common sense right now is that you should love your job and work to find meaning. That’s a common-sense thing that’s really hard to challenge. But it’s becoming clear that the common sense is actually not true. It’s not enough to shake off the common sense, it’s actually a force of change. You can’t just be like, “I am now awakened.” It requires actual political struggle.

What we’re doing right now is my side hustle. But I prioritize this type of work over writing ad copy or whatever because it’s more interesting and gratifying, even though I could make a lot more money doing something else. To put it bluntly: Am I insane?

The industry of journalism is socially important, necessary work that shouldn’t become a luxury product for rich people. It used to be that there was a newspaper in every town—you had the people who were the firefighters, you had the people who were the teachers, and you had the people who were journalists, and those are all necessary things to make your town function.

The pandemic gave us interesting language to talk about essential work. We had a real experience of asking ourselves, “What do we need? What is actually necessary for sustaining human life? What is the work that is actually necessary to do, and how do we distribute that work?” And right now, the necessary work of journalism is being done in a handful of places as a luxury product. You’re getting this downward pressure on the thing, which means downward pressure on the quality of the product. Journalism is a vital resource to having an informed society, and with the death of local journalism, look at our politics! These things are connected.

STREAM: Sarah Jaffe discusses and reads from Work Won’t Love You Back at 5 pm Tuesday, Feb. 22. Register for the Zoom event at powells.com. Free.

Jobs Issue 2022: A Historic Labor Shortage Is Making Oregon Employers Downright Desperate

We Didn’t Start the Labor Shortage

Oregon Employers Will Put Thousands of Dollars in Your Pocket if You Get Hired

Telehealth Changed Doctor Appointments and We Have the Pandemic To Thank for That

The Cuddling Industry: Supply, Demand and a Statewide Rebound of the Self-employed

Portland-area Startup Radious Found a Better Place to Work From Home: Someone Else’s Home

“Work Won’t Love You Back” Is a Harrowing Read With Hope for the Future