Are there people who hike in forests and don’t think about murder at least once? How strange! Liberating, maybe, but irresponsible. After all, every hike starts with clearing out my car to deter a smash-and-grab at the trailhead, which is certainly not murder but has me on guard for crime. I’ve already texted the name of said trailhead to my family so that they can look for my body if things go awry. (Don’t roll your eyes; these are basic safety measures.) But then there are the errant death thoughts that float through my head midhike. A step too close to the edge of the path and down the cliff I tumble. Is that hiker a peaceful nature lover, or a violent criminal stalking his prey? What if the Big One strikes and I’m crushed by trees, or I survive but I only have this half-full water bottle and a protein bar?

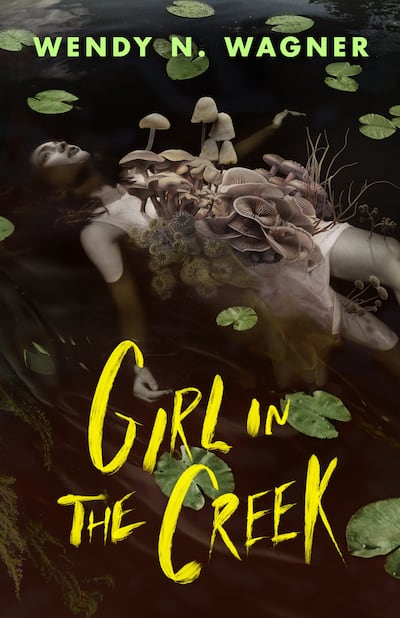

Anyone else whose brain seems to thrive at the intersection of Pacific Northwest forests and true crime might also be drawn to Oregon author Wendy N. Wagner’s new eco-horror novel, Girl in the Creek (Nightfire, 272 pages, $28). The creepy cover image alone might do it: a lithe, beautiful, very dead young woman floating in a creek with mushrooms growing out of her torso. Wagner nails the soggy setting in the Clackamas River wilderness and sets up a lot of intrigue with multiple missing-girl flyers and some hints of the supernatural. The second half of the book, though, veers hard into body horror that might be a bridge too far for some readers.

The protagonist of Girl in the Creek is Erin Harper, a journalist for the fictional Oregon Traveler magazine. Erin is writing an article about rafting and tourism on the Clackamas, but she has an ulterior motive. Erin’s brother Bryan was last seen alive in the Mount Hood National Forest five years ago before disappearing without a trace. She pitched the article to her editor in hopes of being able to do double duty writing her travel feature and solving the mystery of Bryan’s disappearance. When she arrives at the fictional rural town of Faraday, Ore., she learns that there is an epidemic of missing hikers, their cases all gone cold. Things really get going when Erin and another hiker discover a dead body in a creek.

Wagner writes in the book’s acknowledgements that she was inspired to write Girl in the Creek after she and her husband took a drive along the Clackamas River during the pandemic lockdown. And Wagner nails the descriptions of our particular brand of greenery:

“The air smelled bracingly of forest—decomposing pine needles, wet moss, and the verdant briskness of freshly budding leaves. The river, higher than usual after a warm, wet March, grumbled in its banks. Other than that, though: silence.”

The first half of the book leans into the small-town true crime story, with a big cast of townsfolk who are all both sexy and potentially murderous, to varying degrees. The cast is actually a little too big: An early scene at a brew pub is a handy way to introduce the characters but is disorienting with too many similar-aged, outdoorsy people coming and going. Detail-oriented readers and crime-solvers might want to jot down a character list to help them through the first 100 pages or so.

What start as glimmers of the supernatural—something called “The Strangeness,” sparkling mushroom spores on the edges of Erin’s rain jacket—eventually become the centerpiece of the novel as Erin starts to uncover the mysteries in Faraday in the second half of the book. As the editor-in-chief of Nightmare magazine and author of more than 50 short stories, Wagner’s expertise in horror shines through once the Strangeness takes over. Just so people know what they might be getting into, though, at one point Erin recoils from “the wriggling threads in the cuts on his face and the strings that had come out of his eyeball.”

The body horror was too much for this reader. And the book didn’t quite invest enough in the emotional lives of Erin and the other lead characters to motivate me through the stringy eyeballs, though a love interest between Erin and a Portland Parks & Recreation employee named Madison comes close. Once the forest fungi took over—those mushrooms on the cover are a clue—I checked out a little. I finished the book but had to avert my eyes a few times. It turns out that my imagination is happiest dwelling on real-world forest murders.