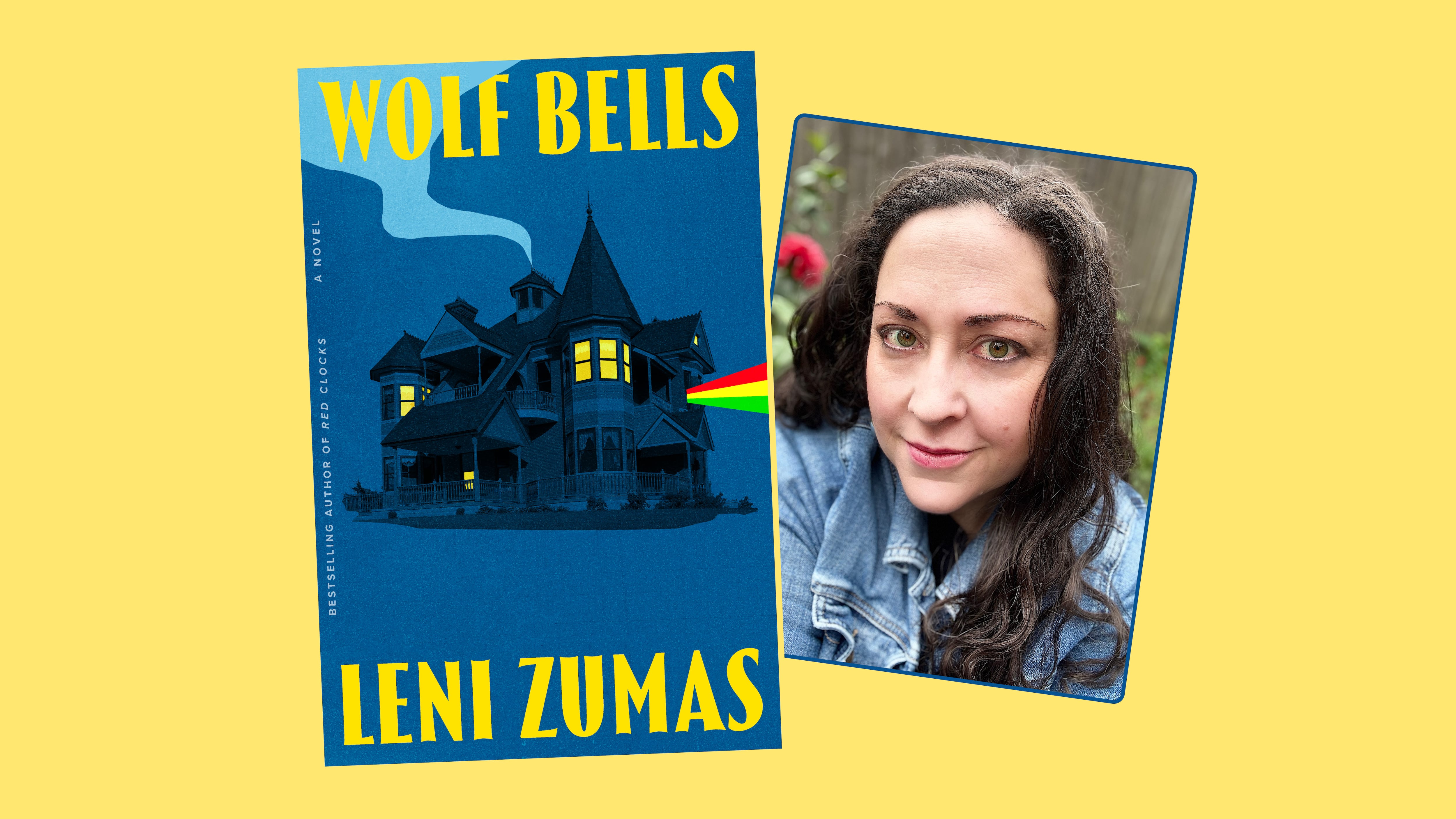

Below is an excerpt from Wolf Bells (Algonquin Books, 224 pages, $28), the recently released novel from Leni Zumas.

Here at the brink of a forest on a cliff above a river in a valley between haunches of limestone was a steep brown ship of a house. The roots of the trees circling the ship had met corpses, been shredded by hooves, and seen a freak summer when every live thing froze. On the concrete foundation that sat on the dirt that sat on a crust of basalt were twenty rooms, nine bathrooms, and one porch. Metal and plastic and clay, glass and acrylic and wood, two kinds of cedar, three kinds of fir, a hundred deep winters stood through. Here were the dead and the living together—things that had happened and were happening, hair and skin from gone bodies dusting bodies in motion. Rooms of leaky bodies with their wishes and toenails and teeth and regrets, their tampons and catheters, nipples hard and soft, a two-haired mole on a cheek. Static jumping in the dress of a doll on a shelf.

In 1919 a sea captain had brought his wife hundreds of miles from the damp coast to this valley, hoping the mountain air would cure her. In less than a month she was dead. Infected corpses weren’t allowed on trains, and no cemetery would agree to take hers, so he bought land on the bluff above town and buried the body himself. Then he paid other men to build a house near the grave. Thick lengths of old-growth fir, an aquarium with mechanical air pumps. Extravagance unheard of, then, in these mountains. The cook and housekeeper hired from town brought back reports of their boss’s profligacy: the purchase for each child of a personal horse, or his insistence that the table linen be washed and ironed after only one week of use. The housekeeper said the captain sprayed his scrotum with cologne, for what reason she’d die before trying to guess.

Minerals from the grave of the captain’s wife had turned into honeysuckle, been plucked, lived in water on the table, floated up their noses. Here they lived, backed up against a forest on the fringe of a dingy town, alone and together in these rooms.

Here are the rooms, and what there was room for.

In the hall at the top of the house, the captain’s great-granddaughter stood waiting to escort a soon-to-be-ex-resident downstairs. He had broken the rules too often, refused to do the few things required of him. She hated being in charge of the situation, but the House was hers, legally at least, so she stood firmly while he slammed and kicked and muttered. She’d given him plenty of chances to succeed at his duties—to join the other residents for dinner, play chess or watch TV with them, and every Tuesday bring the trash and recycling down to the road—but he was only interested in recording songs in the room he had soundproofed with thick gray panels of egg-crate foam and what looked like military-grade canvas stapled to the floor.

“This is such bullshit,” he said, shoving plastic baggies of beef jerky and dried mango into a backpack. “I did make an effort. Those people aren’t easy. The asshole with the huge forehead accused me of poisoning the night snack, did you know that? I literally did not feel safe.”

He had been at the House for six weeks. Caz referred to him as Neck Beard unless he was standing right there, in which case she called him buddy. He was an anti-cement activist who, when he wasn’t chaining himself to construction equipment, worked remotely for a consumer-research firm. He’d conducted his work calls in the library, within earshot of all. Whenever someone answered but refused to do the survey, he would pretend to be calling about their tax returns and say, “We have found troubling irregularities.”

“I had high hopes for this place,” he told Caz. “Like, the concept is really cool. Whereas the reality—”

“You mean the concept that you could live here for free if you participated in the community? A concept you seemed unable to grasp?”

“Oh, I grasped it. I grasped the fuck out of that little concept.” He picked up a stray piece of paper, stared at it, crumpled it, and threw it into a corner. “But whatever. This is turning out for the best, because I don’t actually want to live in an unheated nursing home.”

“Intergenerational community,” she said.

“Dude, this is a nursing home,” he said. “With, like, add-ons.”

Caz didn’t need to justify the House to him. He didn’t take her seriously, anyway; she saw the disdain in his watery eyes. Saw him not see her, not be curious in the slightest about who she was or who she had been.

The rag rug under her feet stank of piss. Walking the dog was another House chore currently being neglected, though not by Neck Beard. The hallway on this floor had smelled bad even before the dog started peeing on it.

“Key?” she said.

“Huh?”

“I’ll need your house key.”

He scratched the dark-blond fuzz on his jaw. “No idea where that is, to be honest. But don’t worry, I’m not planning to come back in the dead of night and steal your TV that was manufactured before my birth.”

“Mail it to me when you find it,” she said.

“Best of luck with your concept,” he said.

“Dick,” she whispered. He was a sweaty white boy in a cowrie-shell necklace who thought he knew more about music than she did and whose zeal for battling environmental destruction was obviously performative.

At the end of the hall was a small window tilted diagonally under the eave, a witch window, its crooked angle meant to prevent witches from steering their broomsticks into the house. Through the pane came a slippery light that fell on both of them as they lugged his bags to the stairs, the weak sun seeping through clouds massed above the valley to hit the House and the trees and the river below.

Excerpted from Wolf Bells. Copyright © 2025 by Leni Zumas. Excerpted by permission of Hachette Book Group. All rights reserved.