Remember passing notes in junior high school—how news spread through little, sometimes intricately folded, sheets of notebook paper handed covertly between desks or while passing in hallways? Well, since our “leadership” has the emotional regulation skills of a bunch of junior high exiles, it seems we’re right back to spreading news by physically writing it, assembling it, or typing and sharing it ourselves, hand to hand (more or less).

Which is all to say, public trust in legacy media feels just about dried up—save for Vanity Fair’s cunty antics, praise be—but the fourth estate arguably lives on in alt media, evidenced not only by what you’re reading right now, but by the proliferation of revolutionary zines peppered throughout free and public libraries citywide. Eightfold, eight-page zines—easy to DIY and not staple dependent—have been an easy, all-ages crafternoon project for generations, but now, in this new dawn of discontent, those tiny eight-pagers are looking less like rainy-day projects and more like vital resources for community action, support and, ultimately, resistance.

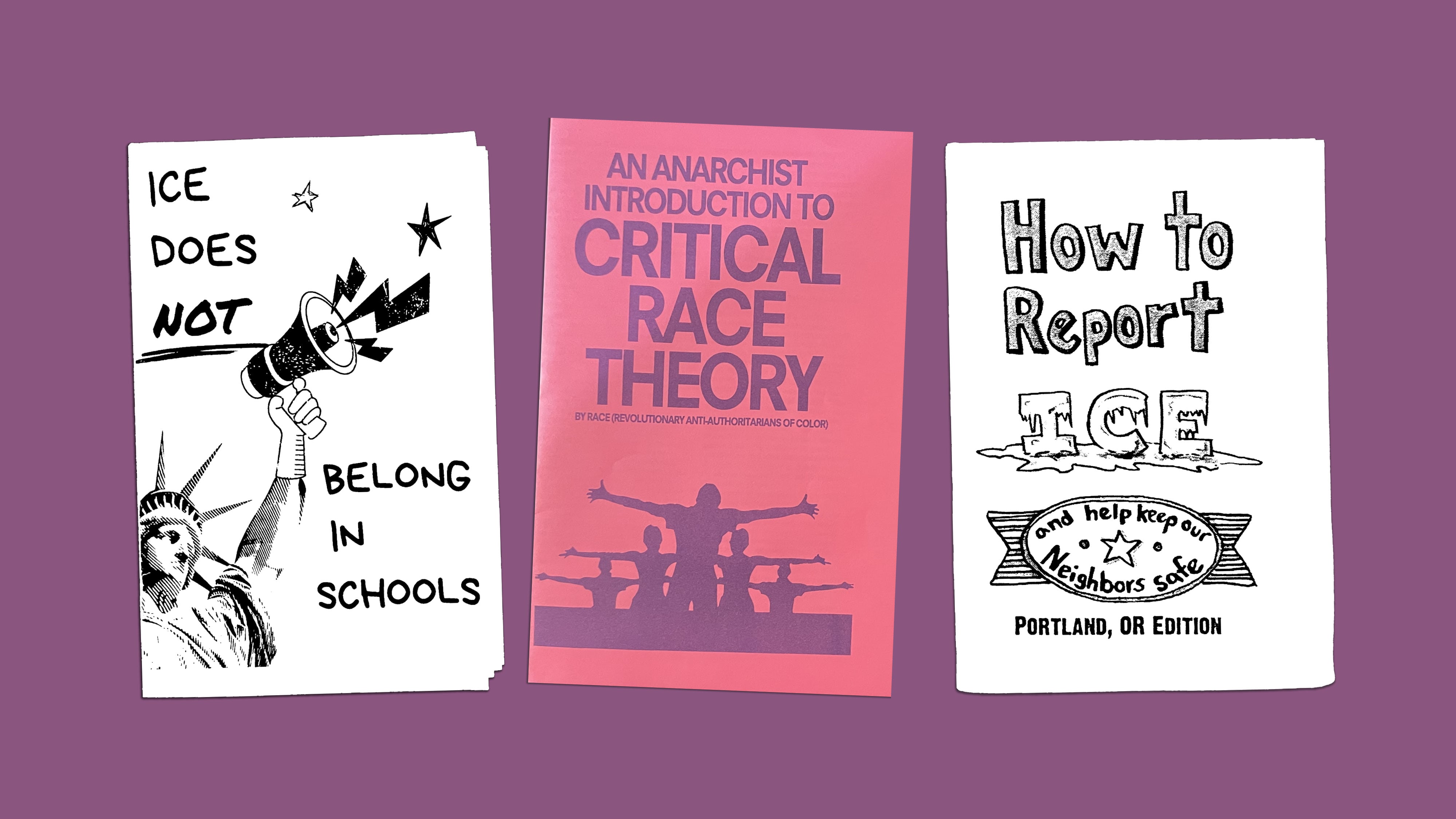

Eight-page zines like How to Report ICE by Megan Piontkowski and ICE Does Not Belong in Schools can be found around town in free library boxes, and both sit on resource tables and in the zine library at Portland Community College’s Cascade Campus. Both offer straightforward resources like rapid response plans and ICE hotlines, as well as more complex tools for community members navigating immigration, filling a vacuum created by our current dearth of trustworthy sources. Similarly, Well, How Did I Get Here asks eight pages’ worth of questions, the answers to which very clearly explain precisely how we got here.

But zines also have the capacity to fill the vacuum left by late-capitalist, post-quarantine isolation. Half-page zines that lined tables at this year’s zine symposium, like An Anarchist’s Introduction to Critical Race Theory and Panther Sisters on Women’s Liberation are classic, collage-based zine primers on the radical blueprints generations before us followed in their pursuit of equity and liberty, prioritizing community care and direct action over screaming into the abyss. And like their diminutive kin, they are rich with resources that encourage further investigation, conversation and, ideally, inspiration.

Another facet of zinedom that feels especially poignant right now is that it gives us a method to create physical copies of historical media that are quickly being eroded. Case in point: A zine showcasing the poetry of one of the best-known poets in pre-19th century America, the enslaved Phillis Wheatley Peters, sits among resistance zines in the PCC Library—a delicate and heartrending reminder of exactly what we are against and what we are fighting for.