In a city with a reputation for cultural homogeneity, Black Portlanders would like a word otherwise. The Portland Art Museum, arguably the city’s cultural center, is standing 10 toes down in support. PAM’s new Black Art and Experiences Initiative, a permanent, multigallery project debuting with the reopening of the Rothko Pavilion, aims to embed Black art, artists and audiences into the core of the museum’s curatorial practice, programming and institutional culture.

The initiative includes four galleries dedicated to Black art, activations and community reflection; robust partnerships with Black-led organizations; an artist-driven residency model; and deep community engagement guided by Portland’s own community of Black artists, curators, advocates and creators, with leadership by ambassador Tammy Jo Wilson, an artist, curator and arts organizer who sits on the board of the Regional Arts & Culture Council.

“We’ve tried to ground the Black Art and Experiences Initiative in community input, creating a sense of community beyond just art on the walls,” says curatorial coordinator Jaleesa Johnston. “Historically, the museum hasn’t always engaged with Black communities in this way. The initiative aims to make community engagement with Black creators, scholars, and audiences a regular practice.

“It will cement the presence of Black people in Portland and the Pacific Northwest and shift how the museum operates,” Johnston continues. “We’ve become more community-centered.”

The initiative materialized as a natural evolution of the museum’s increasingly Black-forward programming. A 2017 exhibition called Constructing Identities, a historical display of contemporary paintings, sculptures, prints and drawings by prominent Black artists alongside works from the 1930s to the midcentury civil rights era, marked the first intentional moment that the museum addressed a broad array of Black artists and art histories. In 2018, the Hank Willis Thomas exhibition All Things Being Equal brought another complex layer of the Black experience to the museum. Then, in 2023, artist and cultural archivist Intisar Abioto curated the landmark exhibition Black Artists of Oregon, which became a tipping point. Instead of hushed galleries and stark corridors, the museum overflowed with cacophonous joy.

“The Hank Willis Thomas exhibition involved community engagement and a fellowship position with writer Ella Ray, who embedded the exhibition in Portland, connecting with community partners and creating a physical space for activities,” explains Ian Gillingham, PAM’s head of press and publications. “Through that experience, we realized that being intentional and inclusive in exhibitions is more welcoming than simply presenting art to the public.”

Abioto’s show, meanwhile, represented a seismic shift in how Black Portland engaged with the museum.

“Black Artists of Oregon intertwined with Black people in Portland,” Johnston says, “creating a sense of community beyond just art on the walls.”

Such is the energy of the Black Art and Experiences Galleries: creativity-exalting cultural community center where Portlanders encounter Blackness as a subject—not a theme, not an object, not a historical chapter to be examined.

“It’s an invitation, not appropriation, not tokenization, but appreciation,” says Rukaiyah Adams, chief executive officer of The 1803 Fund, a major contributor not only financially but philosophically to the Black Art and Experiences Initiative. “For the wider population, there’s work to do. And for us, the work is claiming subjecthood, agency, vision, authorship. We’ve been coming to the table as objects. George Floyd showed us the cost of that. This gallery is a shift into subjecthood.”

“Art is not isolation,” Adams adds. “It is cultural infrastructure.”

Now open to the public for more than a week, BAE is more than a collection of galleries. It is an initiative dedicated to uncovering history, highlighting regional artists and expanding educational programs with PPS schools, including art-making opportunities in the Black Art and Experiences Galleries. “The initiative aims to make community engagement with Black creators, scholars, and community a regular practice,” Johnston says.

Perhaps the most compelling piece of the Black Art and Experiences Galleries is the newly installed Thelma Johnson Streat Promenade, a windowed corridor that connects Southwest Park and 10th Avenues streetside and leads directly from the Rothko Pavilion into the galleries themselves.

“We knew BAE would focus on emerging artists, be visible from the street, and be vibrant—not hushed,” Adams says. “In honoring Thelma Johnson Streat, we are not escaping the realities of today. We are responding to them. We are saying that even in hard times, we can create beauty. And that beauty can still be a bridge.”

Exploring each of the four BAE spaces, it becomes clear that both legacy and lineage guide the work. Past exclusion and future permanence shape long-term planning. Rather than fearing national politics, the work demands that people show up for each other with boldness, clarity and joy. PAM’s collection now contains more than 400 works by more than 60 Black artists, and the collection is growing.

“Arts investment is not frivolous,” Adams says. “It is a third space, a cultural bridge, and a platform for agency. The gallery’s naming and ethos reject the white gaze in favor of Black subjectivity.”

Jeremy Okai Davis, Otis Kwame Kye Quaicoe and Carrie Mae Weems are among the familiar names that characterize BAE’s print gallery, their works telling contemporary stories about Blackness through varied diasporic lenses. The print gallery also includes pieces by Jacob Lawrence, Romare Bearden, Kara Walker, Gary Simmons and Derrick Adams, among so many others.

BAE also includes spaces for classes both messy and techy (and both) and the resulting small exhibitions they are set to produce. The spaces also afford artist residencies, archival projects, performances, panels, workshops, and film series (in partnership with PAM’s Center for an Untold Tomorrow).

In the installation gallery, former Portlander Mickalene Thomas’ Do I Look Like a Lady? holds particular weight—a multimedia experience juxtaposing comedians, performers, and artists discussing Black womanhood with candor. Anyone can enjoy the installation, but to say it hits differently for Black women would be an understatement. I wept tears of joy, identity, and remembrance several times during its brief runtime. But perhaps the most powerful moment of the inaugural visit occurred when I strolled through the new promenade, where the word “Tenderhead,” formed in pink neon, hangs in a massive display window.

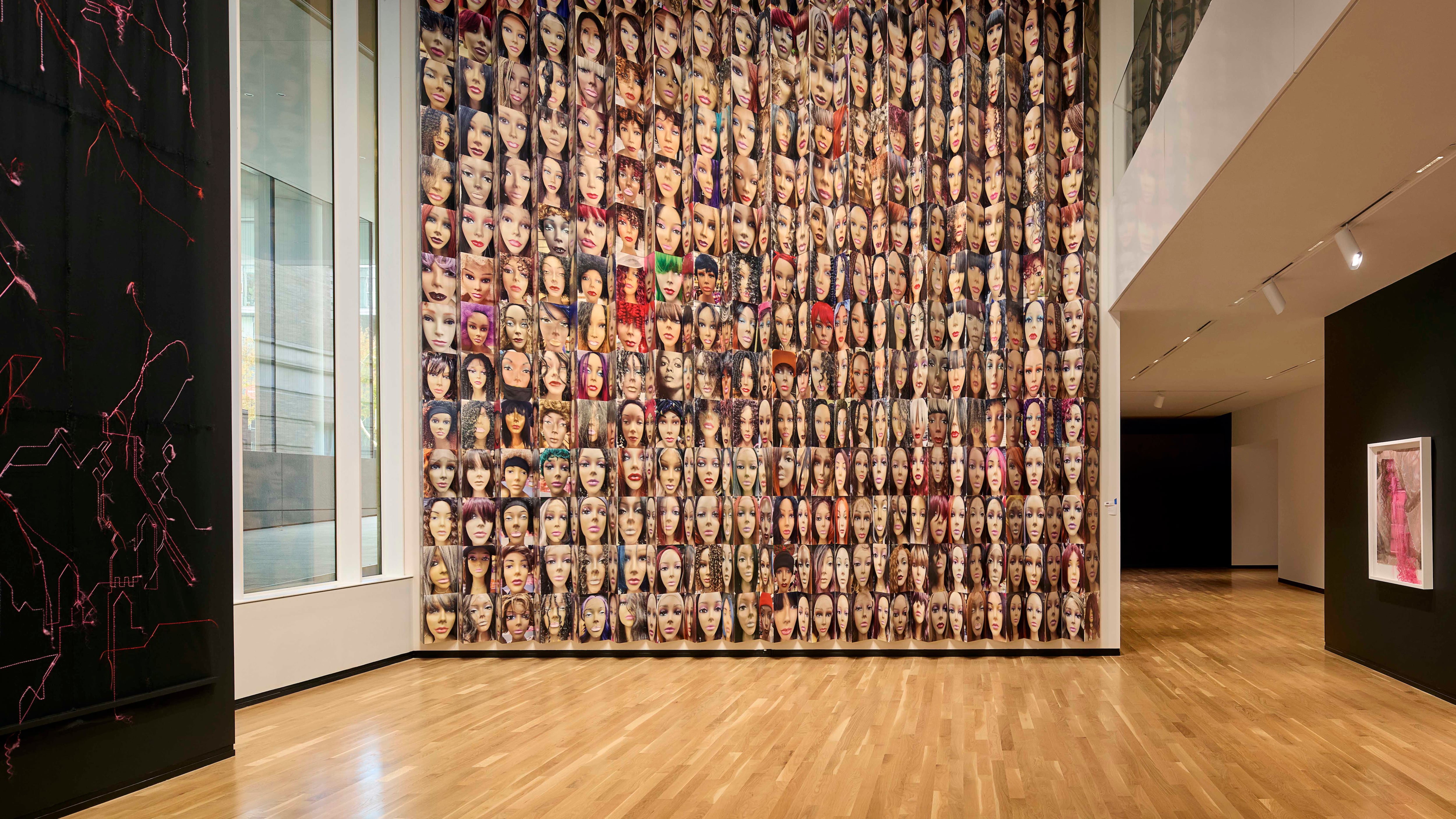

Behind it, spanning two stories of wall space, is an installation by artist Lisa Jarrett: a seemingly infinite array of geometrically arranged, tightly cropped images of wig heads, each adorned with a different technicolor synthetic unit. A concentrated expression of a singular yet commonplace Black experience; a visit to the beauty supply store.

The word “tenderheaded” describes those less tolerant of having their kinks and curls detangled by the fine-tooth combs of mothers and grandmothers. I wear my hair short because I am, in fact, too tenderheaded to wear it otherwise. Seeing the familiar face molds, raw lace bands, and painted-on makeup styles of Jarrett’s images evoked such a pang of nostalgia, time, and place that I was brought to tears. I was picking up hair care products. I was with my mother as she tried on wigs for church and work; I was with my grandmother as she chose wigs to cover her patchy, post-chemotherapy scalp.

“We’re not bald, Brianna,” her memory whispered as I recognized a wig in Jarrett’s display. “We have wigs.”

PAM has always felt like a sanctuary, but with this renovation and the unveiling of the Black Art and Experiences Galleries, it has become something holier than that—embracing its role in shaping Portland’s landscape, not just in terms of arts and culture, but in the future of perceptions of race in America.

“Wherever we are,” Adams says, “is the Blackest place in the world.”

SEE IT: Black Art and Experiences Galleries at Portland Art Museum, 1219 SW Park Ave., 503-226-2811, portlandartmuseum.org. 10 am–5 pm Tuesday–Sunday. $27.50, $24.50 for military, age 65+ and adult groups of 12 or more. $22.50 with student ID. $5 Arts for All. Free ages 17 and under, free for all on First Thursdays.