Portland was the defining city of the 2010s.

As the decade closes, no American city plays such an outsized role in the national imagination. Sure, every town has an exaggerated sense of its own importance, but any similarly sized burg—say, Detroit—would have trouble identifying 20 days when it grabbed the country's attention.

We struggled to narrow the list to 20. (Sorry, fluoride haters!) As the decade opened, the Rose City was still a hipster haven: gritty, obscure, a little punk. Then Portlandia happened. Then weed happened. Then the riots started.

You get the idea. Portlanders repeatedly seized the national stage, with triumphs, scandals and fights. In this edition, WW looks back on the moments that proved pivotal, and brought the national media scrambling back to the banks of the Willamette.

What stood out to us was how drastically Portland's reputation had changed. This city started the decade as Quirksville, U.S.A., and will end it as an Antifa war zone.

That image isn't completely fair—but then, many of the big days of this decade show Portland is still trying to define itself. Are we a blue-collar timber town despoiled by tech yuppies, a bastion of progressive thinking, or a pack of self-indulgent racists who haven't confronted our own past?

Maybe we're all three. The most eventful days in our city emerged from that internal conflict—a drama that played to a worldwide audience. In the following pages, we look at the moments when that struggle crystalized: a wedding cake that was never made, an ad for apartments that started a renter revolt, and death threats over burritos.

Some of these moments were painful. Others were absurd. But being famous is messy. And this is a window on the decade when Portland blew up.

Jan. 21, 2011

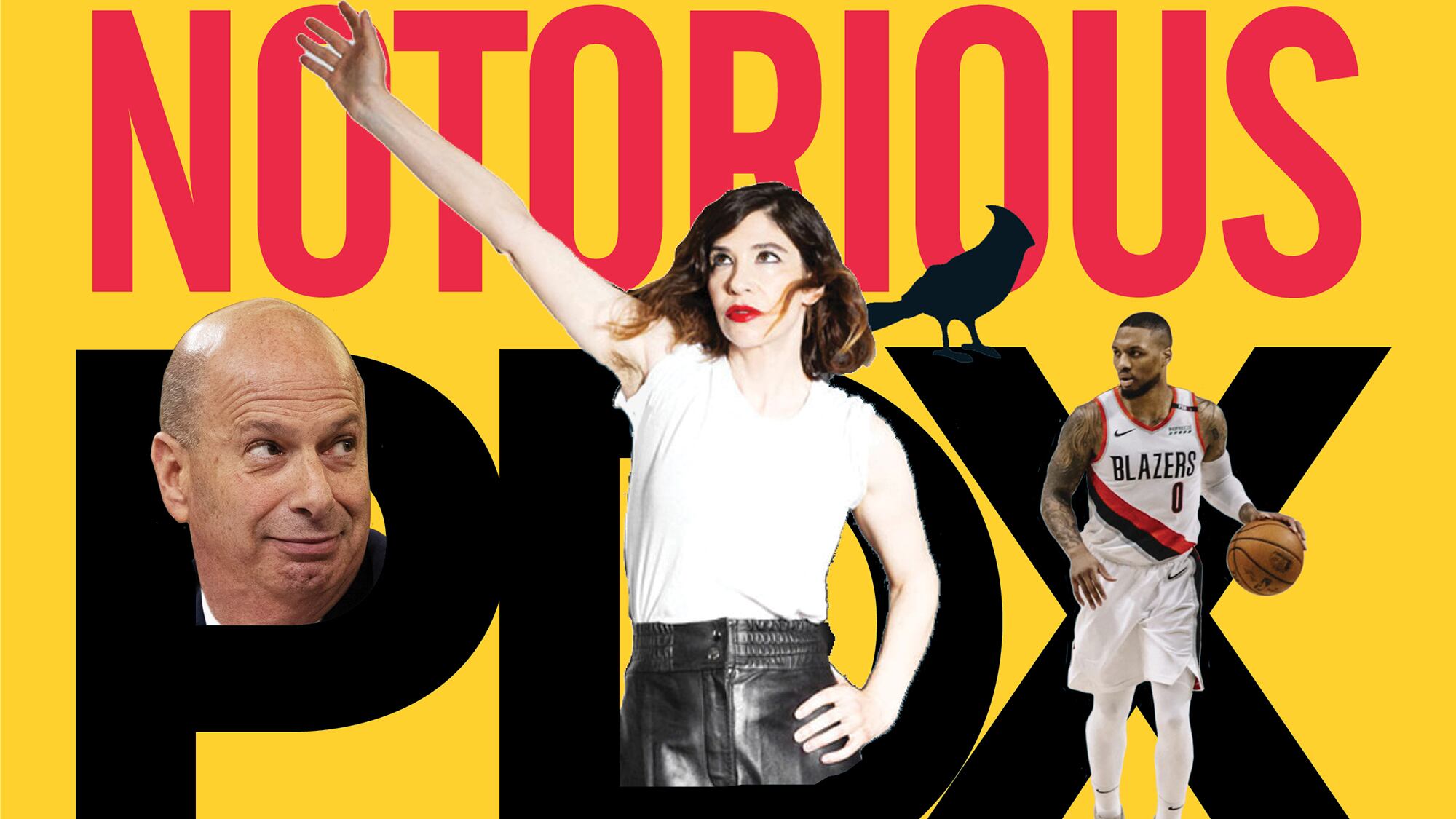

Carrie Brownstein premieres her TV show, Portlandia.

What she did: Along with Saturday Night Live veteran Fred Armisen, Brownstein, the guitarist for legendary punk-rock group Sleater-Kinney, made jokes about bird art, artisanal knot stores, and Portland as a retirement village for 20-somethings. Hilarity or calamity ensued, depending on your perspective. What is in little doubt is that the hit TV series stereotyped Portland for much of the world as a twee preserve where privileged liberals argue over tiny problems.

What she said: "Whole Foods temporarily pulled kombucha from their shelves on account of the alcohol content," she wrote in a November 2010 essay for WW on what's funny about Portland. "When they were able to restock the item, the store on East Burnside painted the words 'Kombucha Is Back' on its window. In any other city, something writ with such fervor would have read, 'Jesus Has Risen.'"

Why it mattered: Few would have guessed a sketch comedy show on an obscure cable network could become such a national phenomenon. The show put Portland on the map—and the city resented it. Much of the debate centered on the show's intent: Was its mockery of adult hide-and-seek leagues meant to hold a funhouse mirror up to Portland's quirks, or was its portrayal of the city as a playground for liberal narcissists a self-fulfilling prophecy?

Either way, once rents started going up and everyone's favorite bars were demolished and replaced with apartments, the show became a scapegoat for Portland's growing pains. A local band wrote a song excoriating Brownstein and Armisen for "exploiting our town." Bumper stickers declared, "Fred and Toody, Not Fred and Carrie." (Fred and Toody Cole led garage-rock band Dead Moon.) A feminist bookstore that inspired a recurring sketch declared that Armisen dressing in drag was transphobic. "I'm not sure there is all that much difference between Portlandia mocking the characters they focus on and Trump mocking a reporter with a disability," opined local author Monica Drake.

For her part, Brownstein denied any malice. "The show has merely been part of an ongoing dialogue some of us were having five years ago and more of us are having now," she told WW in 2017. "It's a conversation I appreciate, and I think we should keep having."

What happened to her: Brownstein lives in L.A. now, where she's redevoted herself to Sleater-Kinney. Your favorite bar, meanwhile, remains closed. MATTHEW SINGER.

Feb. 18, 2011

Photos surface of 1st District Congressman David Wu in a tiger suit.

What he did: U.S. Rep. David Wu (D-Ore.) was the first Taiwanese American elected to Congress. In his seven terms, Wu served his district, which extends from the west side of Portland to the coast, with little distinction—until 2010, when he began acting erratically.

As his behavior worsened, WW published a damning cover story that included photos of Wu dressed in a tiger suit. The photos had been taken four months earlier, just ahead of a hotly contested re-election campaign. Wu held on to his seat, but seven staffers resigned after the election—and the photos helped explain why.

What he said: "Cut him some slack, man. What he does when he's wasted is send emails, not harass people he works with." Wu wrote these lines in an email to campaign staff while pretending to be his son. It was one of several messages Wu sent Oct. 30, 2010, to alarmed staffers—including the tiger-suit shots.

Why it mattered: Wu's behavior became increasingly bizarre and an embarrassment to his party. In July 2011, a female family friend accused Wu of forcing her to have sex with him when she was 18. Wu said the sex was consensual, but House Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-Calif.) opened an ethics investigation and Wu quickly resigned. His downfall came only a month after the resignation of a more prominent colleague, U.S. Rep. Anthony Weiner (D-N.Y.), in the wake of a sexting scandal. The two Democrats, who entered the House the same year, were both undone by what was then a newish medium—the cellphone photo.

What happened to him: Wu, who practiced law in Portland before his election to Congress, stayed in Washington, D.C. He often visited the House floor, a privilege given to former members, and told BuzzFeed in 2014 he enjoyed another congressional tradition: Wednesday fried chicken lunches. Wu today reportedly practices law and advises Chinese clients on how to operate in the U.S. He could not be reached for comment. NIGEL JAQUISS.

Nov. 13, 2011

Occupy Portland defies an order to leave downtown parks.

What they did: For 39 days, hundreds of protesters seeking economic equality had camped in Lownsdale and Chapman squares, taking part in a nationwide rebuke to Wall Street and erecting a tent village adjacent to City Hall that alarmed officials and downtown business owners. As conditions grew increasingly chaotic and squalid, then-Mayor Sam Adams issued a deadline for occupiers to leave. When the clock struck midnight Nov. 13, nobody left—in fact, some 4,000 onlookers gathered to watch a defiant celebration, as protesters kissed atop the iconic Main Street elk statue.

Hours later, riot police marched into the camp at dawn and tore it down. The campers dispersed. The occupation was over.

What they said: "Whose streets?" the protesters repeatedly chanted. "Our streets!"

Why it mattered: Little Beirut was back. The Occupy protests reawakened a dormant street-protest movement in Portland, which would be echoed later in the decade by militant antifascists protesting President Donald Trump.

The camps also revealed the desperation of people living on the margins of the city: Among the American Occupy camps, Portland's stood out as a magnet for homeless people struggling with addictions and mental illness. The organizers couldn't adequately care for the people who arrived, but that wasn't the point: The protest exposed how many people had fallen through the social safety net, a problem that would only grow more dire as the decade progressed.

What happened to them: Some of the organizers remained active in leftist activism, but Occupy folded into other protest movements—often against the Police Bureau that had cracked down on campers. Adams, who issued the evacuation order, moved to Washington, D.C., lost his job after a harassment accusation, and now cleans graffiti in his North Portland neighborhood. He says the camps were eye-opening. "Many Portlanders saw for the first time the humanity of those suffering from homelessness," he says. AARON MESH.

March 2, 2012

Patricia McCaig can't contain the bad news that the proposed Columbia River Crossing is too low.

What she did: For a decade, visions of a new Interstate 5 bridge across the Columbia River from Portland to Vancouver beguiled policymakers, construction firms, consultants and light rail advocates. The Columbia River Crossing was a two-state effort, with Washington and Oregon pledging to split the $2.9 billion price tag.

On the Oregon side, the key player was Patricia McCaig, the onetime chief of staff to Gov. Barbara Roberts who parlayed her skills—she sometimes called herself the "Princess of Darkness"—into a position as the political fixer for the CRC. In 2011, McCaig and her colleagues privately received bad news: The proposed bridge would stand only 95 feet above water level, 30 feet lower than the U.S. Coast Guard said big ships needed to pass underneath. After The Columbian in Vancouver broke the news in March 2012, McCaig stayed silent. She later tried to convince Oregon lawmakers the height issue was new information.

What she said: "It was kind of a surprise to many people, including the governor," McCaig testified in September 2012.

Why it mattered: The revelation that project sponsors had spent $140 million on a bridge design the Coast Guard would reject was difficult for McCaig to overcome. On the Oregon side, a ragtag guerrilla squad of skeptics led by economist Joe Cortright poked holes in the rationale for the new bridge: The highway departments' traffic and financial projections were wrong, they argued, and creating new vehicle capacity would not relieve congestion. Meanwhile, light rail-hating conservatives in Clark County said MAX trains should stay in Oregon.

The economic analysis and political battles might confuse the average citizen—but a bridge 30 feet too low was a problem anyone could understand, and in many ways it was a turning point for the project. After more than 12 years of meetings and the expenditure of $200 million on studies, plans and environmental work, the project sank below the dark waters of the Columbia River in 2014.

What happened to her: Kitzhaber later called on McCaig to handle damage control on Cover Oregon, the state's failed online health insurance exchange, but after he left office in 2015, McCaig pulled back from political work. (She didn't respond to a request for comment.) The CRC went dark after Oregon pulled the plug in 2014—until last month, when Govs. Kate Brown and Jay Inslee announced they were restarting the process. "This joint effort to replace the interstate bridge is critical to the safety and economies of both Oregon and Washington," Brown said in a statement Nov. 18, "and an important step forward as we invest in the growth of our region."

Cortright remains skeptical. "Transportation departments exist to build things," he says. "All of their arguments are just ways to sell the biggest projects they can do." NIGEL JAQUISS.

Jan. 17, 2013

Laurel Bowman and Rachel Cryer are denied a wedding cake by Gresham bakery owner Aaron Klein.

What they did: Rachel Cryer and her mother walked into Sweet Cakes by Melissa in Gresham to sample cakes for Cryer's wedding to Laurel Bowman. She expected to be met by baker Melissa Klein. Instead, Klein's husband, Aaron, was waiting behind the counter—and asked to know the names of the bride and groom before starting the tasting. After learning the cake would be for a same-sex wedding, he quoted Leviticus—and said his bakery wouldn't make the cake, because of the Kleins' Christian beliefs.

The Bowman-Cryers filed a complaint with the Oregon Department of Justice. Klein posted a copy of the complaint on social media—along with the Bowman-Cryers' home address.

What they said: "Our neighbors had dropped off notes on our doorstep saying they don't agree with what we are doing to this good, decent Christian family," Rachel Bowman-Cryer told WW in 2015. "Your own neighbors are against you, and they've known you for years."

Why it mattered: News of the Sweet Cakes battle spread worldwide. "Sweet Cakes by Melissa has become a symbol for many on the Christian right," Politico wrote in 2015. Conservatives viewed it as an opportunity to roll back civil rights victories that would eventually lead to U.S. Supreme Court recognizing the right to same-sex marriage in 2015. Nancy Haque, the executive director of Basic Rights Oregon, the state's leading LGBTQ advocacy group, is prepared to fight. "We support religious freedom as a fundamental value in America," Haque says. "Freedom of religion is not freedom to discriminate, target or hurt others."

What happened next: Labor Commissioner Brad Avakian of the Oregon Bureau of Labor and Industries ordered the Kleins to pay the Bowman-Cryers $135,000 in damages. The Kleins closed their business and paid the damages, plus interest, in 2015. They also raised more than $400,000 on crowdfunding websites and became conservative media darlings. They appealed BOLI's ruling. The case is still stuck in the federal courts. Through their attorney, the Bowman-Cryers declined comment. ANDI PREWITT.

Jan. 31, 2013

Mohamed Mohamud is found guilty of attempting to bomb the holiday tree lighting at Pioneer Courthouse Square.

What he did: A jury decided 19-year-old Oregon State University student Mohamed Osman Mohamud tried to injure or kill thousands of people gathered downtown to watch the Christmas tree lighting in 2010, by detonating what he thought was a bomb in a van parked beside Pioneer Courthouse Square.

It wasn't a bomb. It was the FBI. Mohamud, a naturalized U.S. citizen born in Somali, had been surveilled by the feds for months after an undercover agent contacted him in June 2010, suspecting Mohamud was corresponding with suspected terrorist groups. FBI agents parked the fake bomb van and arrested Mohamud when he attempted to detonate it.

What he said: "I want whoever is attending that event," he told undercover agents, "to leave either dead or injured."

Why it mattered: In some ways, Mohamud's trial felt like a relitigation of legal debates from the decade before, about whether the greater danger came from jihadi terrorism or government overreach to prevent it. After all, there had never been a bomb. Had there been a terrorist? Or was this all a bunch of G-men entrapping a confused kid?

In his 2013 book, The Terror Factory, investigative journalist Trevor Aaronson argued the FBI's counterterrorism program was "backed by $3 billion a year to infiltrate Muslim communities and create terrorists who aren't there." Mohamud's defense attorneys also argued the FBI used warrantless wiretapping to gather evidence on the Beaverton teen—a defense that felt more compelling in the wake of Edward Snowden's whistleblowing on government surveillance.

The jury didn't care. A federal judge sentenced him to 30 years in prison.

What happened to him: In 2015, Mohamud appealed his conviction, attempting to get it reversed on the grounds he was entrapped by federal agents. His appeal was denied and the now 28-year-old is currently being held at a medium-security federal prison in Victorville, Calif. His scheduled release date is July 3, 2036. ELISE HERRON.

Nov. 14, 2013

Dave Dahl rams his SUV into two sheriff's cruisers.

What he did: The co-founder of Dave's Killer Bread had what authorities called a "mental breakdown" and smashed into two Washington County sheriff's patrol cars with his Cadillac Escalade. Dahl, a recovering meth addict who'd done prison time for armed robbery, pioneered organic loaves packed with sunflower and sesame seeds. He upended the regional bread market.

But as WW reported after his arrest, Dahl had relapsed into drinking, and Dave's Killer Bread knew its co-founder was struggling even as it completed a sale to a New York investment firm, making Dahl a multimillionaire. In one frantic night, the redemption story of an underdog baker was toast.

What he said: "Took a month to overcome the immobilizing depression I felt when it hit me just how many people I had let down."

Why it mattered: This decade, Portland saw some of its most popular brands sold to outside investors looking to take boutique products national: Stumptown Coffee, Little Big Burger, Cura Cannabis. Perhaps none was as beloved as Dave's Killer Bread. The Milwaukie bakery used Dahl's comeback as an inspirational parable, a model for others leaving incarceration, and a tough-guy cartoon to entice customers. Dahl's flameout briefly jeopardized the company's national expansion plans—and illustrated the perils of turning one man's day-to-day struggles into a marketing ploy.

What happened to him: Dahl reached a plea deal and served no prison time. The next year, Dave's Killer Bread sold for $275 million to the Georgia-based owner of Wonder Bread. At the time of Dahl's arrest, his bread was sold in 25 states; it's now on grocery shelves in all 50. Dahl moved from Milwaukie into a stunning downtown Portland condo and started collecting African tribal art. He volunteers and donates to Constructing Hope, a program that trains convicts leaving prison for hardhat work in Portland's building boom. "If I can help people get through their own dark times, I like to do that," Dahl tells WW. "We all have our struggles, and I've had some doozies. It takes surrender. to say, 'Look, I need some help.'" AARON MESH.

May 2, 2014

Damian Lillard hits a 0.9-second shot.

What he did: In the words of ESPN announcer Mike Tirico: "Nine-tenths left. A three wins the series. It's Lillard! He got the shot off—it's goooood! And the Blazers win the series for the first time in 14 years!"

What he said: "Riiiiip City!"

Why it mattered: For Portland Trail Blazers fans, it was practically an exorcism: In less than a second, Lillard, "the kid with the big guts," as Tirico called him, vanquished not just the Houston Rockets but the previous half-decade of tragic injuries, front-office bumbling, and playoff disappointments.

But it was more than just a great sports moment. In Portland, it was the coronation of a cultural hero. It didn't matter if you followed basketball or not—whether you were in the arena or at a bar, or walking down the street when you heard cheers erupt from every house on the block, you remember where you were when that shot went in. From then on, if Dame was on the court, you were watching.

In a fractious decade, about the only thing all of Portland could agree on was Damian Lillard. And as long as he's here, everyone can say, it's a great day to be a Blazer.

What happened to him: Whatever did happen to that guy? Let's see. He made the NBA All-Star Team four times. He broke the franchise record for 3-pointers and most points scored in a single game. He rapped with Lil Wayne. And then, in this year's playoffs, he iced another series with an even more audacious shot, this time tacking on a goodbye wave and a memeable ice stare that read, "I've been here before." Because he had. MATTHEW SINGER.

Nov. 4, 2014

Oregonians legalize cannabis.

What happened: Oregonians voted to legalize recreational cannabis, passing Measure 91 by 56 to 44 percent and becoming just the third state to do so.

Carrie Solomon, a Portlander who sold THC- and CBD-infused edibles to medical marijuana cardholders, was sitting on her couch with her husband when she heard the news. "It was a bittersweet moment," Solomon says. "I thought, 'This is amazing,' and then I realized 'Oh shit, this is the real thing now.'"

What people said: "The criminal justice system stopped wasting money on incarcerating people for cannabis, and that's trickled down to more district attorneys not strongly prosecuting other nonviolent drug offenders," says cannabis lawyer Amy Margolis. "It might not feel like an everyday impact, but it is."

Why it mattered: Federally, weed is still classified as a Schedule I narcotic—and holds a spot in the American political psyche as a dangerous substance. But Oregon's legalization was a signal of cannabis's shifting reputation. Margolis says legalization proved Oregonians had "come to grips that what we'd been told about cannabis was a government-created construct." But perhaps what appeals most to the average Oregonian and the state's politicians is the tax revenue from weed sales. This year, that figure topped $102 million.

What happened to the industry: Oregon grew too much weed. Hundreds of entrepreneurs staked a claim in the burgeoning market. That sent retail prices plummeting to $4 a gram, and by 2018 many growers had no buyers for their crop. Prices began recovering this year—just in time for an outbreak of respiratory illnesses linked to vaping. But the industry eagerly limps forward. "The people who have built this industry have proved over and over again to be hyper-resilient," says Margolis. "We've been able to give tens of thousands of Oregonians the chance for economic success." SOPHIE PEEL.

Feb. 13, 2015

Gov. John Kitzhaber resigns after WW exposes first lady Cylvia Hayes' influence peddling.

What he did: Kitzhaber allowed his fiancée, Hayes, to serve as a senior aide while she operated her private consulting business out of his office. Hayes' business overlapped with her public role, creating an untenable conflict of interest, to which Kitzhaber turned a blind eye, even over the objections of his own staff. Reporting by WW and other media exposed more than $220,000 in contracts Hayes received in policy areas on which she also advised Kitzhaber; her use of public resources for personal benefit; and a previously undisclosed "green-card wedding" for which she was paid $5,000.

But the crushing blow was WW's discovery that Kitzhaber apparently sought the deletion of thousands of emails that had been requested by WW from state servers. That revelation led to Kitzhaber's sudden resignation, less than two months into his historic fourth term.

What he said: "It is deeply troubling to me to realize that we have come to a place in the history of this great state of ours where a person can be charged, tried, convicted and sentenced by the media with no due process and no independent verification of the allegations involved."

Why it mattered: Kitzhaber became the first Oregon governor in modern history to resign for ethical reasons. He was the state's longest-serving top executive, and had earned a national reputation as an expert on health care reform (he's a former emergency room physician), displayed a high-level of independence from the public employee unions who dominate his party, and displayed a mastery of the Legislature. He left office under the cloud of a federal investigation.

What happened to him: Neither Kitzhaber nor Hayes was ever criminally charged, but both were later found to have violated state ethics laws, which are civil violations. Hayes' legal troubles forced her into bankruptcy. Today, she runs a life-coaching business from her Bend home and is studying to become a Unity Worldwide Ministries minister, according to recent Facebook posts. Kitzhaber, now 72, is dipping his toe back into health care policy. Earlier this year, he wrote his successor, Gov. Kate Brown, an impassioned letter, urging her not to foul up the state's Medicaid program, which he designed. Kitzhaber recently told health care consultant DJ Wilson he's made five trips to Washington, D.C., in the past year, meeting with health care wonks. "I think of these trips as 'Don Quixote goes to Washington,'" Kitzhaber told Wilson. "Health care reform is probably my windmill." NIGEL JAQUISS.

May 20, 2015

Luke and Jess move into Burnside 26.

What they did: They were two young professionals getting their first apartment in a sleek, new four-story apartment building next to a karaoke bar. Luke and Jess were starry-eyed dreamers. And Portland hated them.

No matter that Luke and Jess weren't real. They were PR creations dreamed up for a promotional video by the managers of Burnside 26 at 2625 E Burnside St. The stunt backfired: Within days of the video's premiere, Portlanders responded with scorn and rage.

What they said: Luke and Jess never spoke. They just smiled at each other and washed their dog at the apartments' dog-washing station.

Why it mattered: If one moment marked the passing of an older, grittier Portland, it was this video. "Luke & Jess—a young, 'attractive,' white, able-bodied, kidless and cool couple—and their gourmet dog essentially carried the flag for 'new Portland,' and planted it atop Burnside 26," says Margot Black, co-chair of Portland Tenants United. "But it became a rally cry that mobilized the have-nots to take action to defend their city from rapacious landlords and developers."

The people decrying change were not wrong in sensing a dramatic shift was underway. New Portland is indeed richer, with higher rents. The real estate firm Apartment List ranks the Portland area as second in the nation for the sharpest rise in average monthly rent over the 2010s. It saw the "fastest growth in the share of high-earning households and the third-fastest growth in the share of workers with college degrees," according to the firm. A construction boom—including Burnside 26—helped temper the rise in rents. Half of new residential building permits issued over the past decade were for apartments—a sharp increase from 30 percent the decade before.

This silly ad also had political significance: Much of the outcry about Burnside 26 originated from an obscure Facebook group known as "The Shed," moderated by a bookstore owner named Chloe Eudaly. She rode a wave of frustration about rising rents into City Hall in 2016. A staffer in Eudaly's office says a policy she passed in 2017 "disincentivizes displacing Portlanders from their homes to make room for developments like Burnside 26."

What happened to them: Eudaly successfully championed a series of tenant protections, including a ban on most evictions for no cause and a cap on rent increases. Other Portlanders rallied around the cause of housing supply—including unpopular apartments. "Like a lot of Portlanders, that was the moment I realized all the new people aren't going away and we have to find a way to coexist," says Holly Balcom, co-founder of Portland: Neighbors Welcome, a pro-housing and pro-tenant activist group. "If relatively rich folks want to live in Portland, we should stack them, pack them and tax them, and use that money to make life better for everyone through better public transit, biking infrastructure, and affordable housing subsidies."

Portland's construction boom has increased supply—and is benefiting the next round of tenants at Burnside 26. The building now offers a month's free rent as an incentive to sign a lease. RACHEL MONAHAN.

July 29, 2015

Greenpeace kayaktivists dangle from the St. Johns Bridge to block a Shell Oil icebreaking ship.

What they did: Shortly after midnight, 13 environmental activists—none of them Portlanders—rappelled over the side of the St. Johns Bridge, prepared to remain suspended for days. Their plan was to prevent passage of the Fennica, an icebreaking ship bound for a Shell Oil drilling operation in the Arctic. For 40 hours, it worked—"kayaktivists" paddled the river below the bridge, onlookers gathered on the shores of the Willamette, and the Fennica, which had been undergoing repairs at Swan Island, was unable to head out to the ocean. But by 6 pm on July 30, the U.S. Coast Guard and Portland police had removed three Greenpeace protesters from the bridge, enough for the ship to pass through.

What they said: "We had overwhelming support from the crowd," said Florida activist Ruddy Turnstone, one of the 13. "People were yelling up to us, calling us heroes. It was wonderful for us."

Why it mattered: Once again, Portland activism drew the national spotlight. (Newspaper editors can't resist a colorful photo.) The standoff highlighted tensions at the center of a city that contains zealous activists and a working harbor. That same year, then-Mayor Charlie Hales tried to act local by blocking a $500 million propane terminal on the Willamette—and his stance contributed to a turn of public sentiment against him.

What happened to them: Seven of the Greenpeace protesters were fined $5,000 for misdemeanor criminal trespassing. The charge was eventually reduced to a violation that was dismissed after each of the seven activists paid a $150 fine and served eight hours of community service. Two months later, Shell halted Arctic drilling, after "disappointing" results from a well off the coast of Alaska. SHANNON GORMLEY.

Oct. 27, 2016

Ammon Bundy is acquitted by a Portland jury.

What he did: Ammon Bundy led an armed takeover of federal property—and got away with it. Bundy, a former Arizona car mechanic, was the ringleader of a group of right-wing militants who for most of January 2016 seized control of Malheur National Wildlife Refuge in the Eastern Oregon high desert. The standoff ended with one occupier dead at the hands of Oregon State Police, and the other militants arrested on a slew of federal charges. But in October, Bundy and his six co-defendants were acquitted of all charges by a Portland jury.

Kevin Sonoff, a spokesman for the U.S. Attorney's Office for Oregon, remembers the acquittal as disappointing. "We still very much believe the conduct was unlawful and believe an armed takeover of [public land] is criminal conduct," says Sonoff. "There was a feeling that this trial mattered and that the result of it was going to have implications for conduct moving forward."

What he said: "To those who disagree with my speech, or our civil disobedience, and may dislike our ideas regarding that the land belongs to the people: Please remember that you do not want free speech to be retaliated against by government officials. If you do not advocate for government to tolerate ideas that it hates, then the First Amendment and free speech mean nothing."

Why it mattered: The militants claimed they were resisting unconstitutional federal overreach on public lands, and Bundy branded himself a humble patriot suffering government abuse. His acquittal came two weeks before Donald Trump was elected president. To some, it felt like an omen: Federal authorities didn't have things under control, and cranky white men could get away with anything.

Amy Herzfeld-Copple, deputy director for the Western States Center, says Bundy's acquittal was an "emboldening and invigorating" victory for the far right. "It signaled that our government either wasn't able or wasn't willing to stand up in the face of paramilitary vigilantism," says Herzfeld-Copple. "It was a loss for democratic governance and a loss for communities who find themselves targeted and harassed by anti-democratic movements."

What happened to him: Ammon Bundy maintains a robust following on social media, where he dots his profile with podcast appearances and advocates for gun and land rights. Last month, Bundy traveled to a ranch in Idaho owned by a family facing eviction and threatening an armed standoff. He left without pulling a gun. On Facebook, Bundy frequently poses philosophical questions to his followers. One of his latest: "If one man gives an order to another man, and that man does not obey, does the man giving the order have the right to kill him?" SOPHIE PEEL.

Nov. 15, 2016

Aminé performs on The Tonight Show and adds a verse dissing Donald Trump.

What he did: Less than two weeks after Donald Trump was elected president, then-22-year-old Portland rapper Aminé made his TV debut on The Tonight Show With Jimmy Fallon, performing his breakout song "Caroline." It went viral, and not because of the half-dozen bananas that lined the rapper's keyboard. Aminé—the son of Ethiopian immigrants—added an extra verse aimed at the president-elect.

What he said: "You can never make the country great again/All you did was make this country hate again."

Why it mattered: Portland established itself as a capital of the anti-Trump resistance immediately after the election—when thousands of protesters jammed interstate highways in fury. They kept coming back, marching through downtown for six consecutive nights. The protests drew derision (Dave Chappelle called them a "white riot"). Aminé's role in all this? He was both a manifestation of Portland's outrage, and a corrective to it—a reminder that immigrants are the first targets of fascism. Also, it cemented his reputation as a rapper who can pump out sunny bangers and deliver social commentary.

What happened to him: Aminé's performance has been viewed more than 4 million times on YouTube. He's now played Coachella, made the cover of XXL, released his major-label debut, Good for You, and moved to L.A. "Caroline" has gone quadruple platinum. SHANNON GORMLEY.

May 17, 2017

Kooks Burritos co-owners Kali Wilgus and Liz "LC" Connelly set off a national debate about cultural appropriation in restaurant cuisine.

What they did: The pair started a breakfast burrito pop-up, then made the mistake of talking about it.

On its face, there was nothing particularly scandalous about Kooks, nor did it seem there was anything objectionable embedded in WW's positive, 400-word review of the food cart. But when our review was published, it touched off a shitstorm that generated many thousands more words on op-ed pages from The Washington Post to London's Daily Mail. What was so offensive? Two white women were daring to cook Mexican food.

What they said: "I picked the brains of every tortilla lady there in the worst broken Spanish ever," Connelly said of an inspirational trip south of the border. "They wouldn't tell us too much about technique, but we were peeking into the windows of every kitchen, totally fascinated by how easy they made it look."

Why it mattered: It was not, of course, the first time restaurateurs decided to explore outside their own culinary traditions. But at a time when progressives were still on high alert following Donald Trump's inauguration, the story exploded like a landmine in the middle of the culture. Critics accused Wilgus and Connelly of preying on "hard-working and low-income Mexican women" and suggested they send money back to the town that inspired them.

Others came to their defense. Journalist Gustavo Arellano, one of the country's foremost experts on Latin American cuisine, argued that appropriation is the bread and butter of the restaurant industry. "Don't cry for ripped-off Mexican chefs," he wrote in OC Weekly, "they're too busy ripping each other off."

A few days after the review went viral, Wilgus and Connelly shut Kooks down, citing fear for their safety after receiving death threats. "The fact of the matter is, this situation will deter people from opening something that isn't of their own ethnicity," said Anh Luu, then-owner of Vietnamese-Cajun restaurant Tapalaya. "Food should just be judged by how good it is."

What happened to them: In the aftermath, Wilgus and Connelly went dark on social media and have yet to fully resurface. Neither could be reached for comment, but their LinkedIn pages indicate both are currently working for Adidas. MATTHEW SINGER.

May 26, 2017

Jeremy Christian stabs two men to death on a rush-hour MAX train.

What happened: A disturbed man named Jeremy Christian shouted a racist screed at two black teenage girls on a TriMet MAX train heading east to Hollywood Transit Center. When three men intervened, Christian cut their throats. Two of the men, Taliesin Namkai-Meche and Ricky Best, died on the train.

What he said: "I hope they all die," Christian told police in the back of a squad car. "I'm gonna say that on the stand. I'm a patriot, and I hope everyone I stabbed died."

Why it mattered: It was the single most traumatizing day of the decade. It stunned and horrified the city. But it didn't come out of nowhere: For months after Portlanders marched against President Trump, the city had been on edge, with small groups of extremists gathering in parks to fight each other. Christian had been a fringe figure even to these fringe movements: He showed up at one right-wing "free speech" march carrying a baseball bat and throwing Nazi salutes. Two days before the MAX attack, WW warned these encounters were growing intense. "While they're not street gangs, the threat of violence is there," police spokesman Sgt. Pete Simpson told the paper. "They're challenging each other—calling each other out."

Christian was intoxicated by that rage. He fueled it, too. A week after the killings, a Vancouver, Wash.-based protest group called Patriot Prayer gathered across from Portland City Hall, met by thousands of Portlanders who wanted to take a stand against right-wing extremism. Most were peaceful, but the day ended in a police crackdown on leftist protesters. A pattern was set that would continue each summer for three years.

What happened to him: Christian was charged with double homicide. Jury selection in his trial is scheduled to begin in January. Last year, Walia Mohamed, one of the two teenage girls Christian targeted, gave an interview to the author of a book on hate crime survivors. "I liked Portland growing up, but I don't feel comfortable here anymore," Mohamed said. "I'm a Somali immigrant and I decided to take off my hijab a few months ago because I don't feel safe. I feel like I'm going to get attacked again." AARON MESH.

Sept. 2, 2017

A teenager tosses fireworks into the Columbia River Gorge.

What he did: Portland resident Liz FitzGerald was hiking in the Columbia River Gorge the weekend before Labor Day when she witnessed the start of a disaster. "I came upon a large group of teenagers," FitzGerald told WW at the time, "and about four people away from me, I saw a young boy lob a smoke bomb down into the ravine." That 15-year-old boy, from Vancouver, Wash., was throwing fireworks off the trail near Punch Bowl Falls while his friends filmed it. The incident FitzGerald witnessed quickly ignited dry brush and grew into an out-of-control forest fire.

What he said: "I apologize with all my heart to everyone in the Gorge," the boy said, in an apology he read aloud to the court in February 2018. "I am truly sorry about the loss of nature that occurred because of my careless action."

Why it mattered: The fireworks sparked a 49,000-acre inferno that rained ash over Portland for days, forced the evacuation of homes, shut down schools, trapped hikers, and indefinitely closed many beloved trails. The fire seemed to signal how vulnerable Oregon's wilderness was to the twin perils of callous overuse and climate change. (In reality, the fire wasn't nearly as clear a symptom of a warming planet as the larger blazes that occur each summer in Southern Oregon—but it was close to Portland, so more people thought about it.) The sheer waste of the destruction made people furious: Online commenters talked about lynching the teenager.

What happened to him: The boy, who remained unnamed in court, was sentenced to five years of probation and ordered to pay more than $36 million in restitution and spend 1,920 hours volunteering for the U.S. Forest Service. If he completes his probation and is not charged with any new crimes, the court may consider forgiving his debt in 2028. Hundreds of volunteers have spent the past two years rebuilding trails, removing dead trees, and repairing unstable terrain. The Eagle Creek Trail, where the kid threw fireworks, remains closed. ELISE HERRON.

Nov. 6, 2018

Jo Ann Hardesty is the first black woman elected to the Portland City Council.

What she did: She made history. The whitest major city in America had the dubious distinction of waiting until 2018 to elect a black woman to its City Council. Hardesty's victory also marked the first time a majority of seats on the council would be held by women.

What she said: "While I'm proud to be the first African American woman to serve on City Council, I want to also acknowledge the disappointment that it's taken almost 150 years for that to happen."

Why it mattered: The diversity is more than symbolic. For years, Hardesty championed police accountability from outside the corridors of power. In the fall of 2016, two years before her election, Hardesty was head of the local chapter of the NAACP, leading protests on the front portico outside City Hall over the terms of a new police union contract. (It was her inability to achieve the change she wanted, she said, that inspired her to run for City Council.) She's at the table now, seeking reforms in the next contract.

What happened to her: She's started to change the way Portland responds to 911 calls—by proposing to send a specially trained firefighter and a contracted crisis worker to some non-emergency situations, instead of a cop.

She sees more change coming. "It's exciting that we're ending 2019 with African American women holding the positions of city commissioner, fire chief and police chief in this great city," Hardesty says. "My hope is, we encourage all people to be able to take those steps and, in this next decade, we see more African American women in these positions because of their experiences and abilities." RACHEL MONAHAN.

June 29, 2019

Andy Ngo is doused with milkshakes by masked protesters.

What happened: A freelance journalist and social media personality named Andy Ngo was covered in vegan milkshakes, kicked and punched by masked assailants during an antifascist march in downtown Portland. Ngo was hospitalized with an apparent brain injury.

What he said: "Where the hell were you?" he asked police officers, minutes after the assault.

Why it mattered: If this were a list of the 20 most violent confrontations between right-wing extremists and masked antifascists on Portland's streets, this incident probably wouldn't make the cut. In the aftermath of the MAX slayings, Vancouver, Wash.-based protest group Patriot Prayer regularly marched in Portland, seeking to brawl with Rose City Antifa and other leftist groups. Sometimes, the fights became unhinged: One year before Ngo was attacked, right-wing marchers battered antifascists with flag poles and cracked a man's skull.

Portland Mayor Ted Wheeler and police struggled to control the mayhem. Ngo, 33, a onetime Portland State University student, made filming brawls into a career, following Patriot Prayer through town and editing his videos to emphasize the most violent moments and make Portland look like a war zone under mob rule. "It's an American pastime to gawk at Portland's lefty excesses," BuzzFeed wrote this year. Ngo provided Fox News the necessary footage—and was loathed by the left for writing stories that portrayed hate-crime allegations as hoaxes.

What was significant about the attack on Ngo was that it took on mythic importance among conservatives, who declared it proof that Antifa ran Portland. (Police fueled an unfounded rumor that the milkshakes dumped on Ngo contained quick-drying concrete.) If the goal of far-right protesters was to bait Portlanders into committing violence on camera, Ngo took one for the team.

What happened to him: The next month, President Trump started mentioning Ngo at his rallies. Trump called him "a single man standing there with a camera who had never got hit and never hit back before in his life." In August, The Portland Mercury questioned Ngo's close association with some of the right-wing brawlers he filmed. He continues to make regular guest appearances on Fox News: "Not a single person has been arrested for beating and robbing me," he told the network last month. Police are still looking for his masked assailants. He did not respond to WW's request for comment. AARON MESH.

Nov. 20, 2019

Gordon Sondland is the star witness in President Trump's impeachment.

What he did: President Trump's ambassador to the European Union, a Portland hotelier, told Congress that the United States had withheld $391 million in military aid to pressure Ukraine to announce an investigation into Joe Biden—and everybody from the president on down "was in the loop."

What he said: "Was there a quid pro quo? As I testified previously, with regard to the requested White House call and the White House meeting, the answer is yes."

Why it mattered: That Sondland would prove to be Portland's most consequential political player in decades was mind-boggling. He had never registered to vote in Oregon. He achieved success in Portland as a financier and the founder of Provenance Hotels. His companies gave $1 million to Trump's inauguration. Trump then named Sondland, who had no previous government or diplomatic experience, as E.U. ambassador.

Sondland's ambition brought him into the orbit of Rudy Giuliani, Trump's personal attorney who was seemingly convinced Ukraine could bolster Trump's re-election hopes. As one of the "three amigos," Sondland, along with Energy Secretary Rick Perry and Kurt Volker, the State Department's special envoy for Ukraine, acted as go-betweens for Trump and Giuliani with Ukrainian leaders.

Initially, he testified to Congress he could remember few details about his Ukrainian adventures. But after other diplomats provided information that placed Sondland at the center of the Ukraine controversy, Sondland gave new testimony that proved more damaging than perhaps that of any other witness.

What happened to him: After Sondland's testimony Nov. 20, he flew back to Brussels, where he's been far quieter on social media than he was prior to the impeachment hearings. A week after Sondland returned to work, Portland Monthly and ProPublica published the accounts of three women who accused Sondland of unwanted sexual advances. Sondland, who had seen his stock rise in progressive Portland after lowering the boom on Trump, was again painted as a villain. He pushed back against the accusations. "These untrue claims of unwanted touching and kissing are concocted and, I believe, coordinated for political purposes," he said in a statement. "They have no basis in fact, and I categorically deny them." NIGEL JAQUISS.