Secretary of State Shemia Fagan and the elections director she forced out late last year, Deborah Scroggin, disagreed whether the agency should publish a website disclosing campaign finance reporting violations.

That’s common practice in other Western states, including California, Colorado and Washington. Each of those states has a searchable database of campaign finance reporting violations—failures to promptly and accurately disclose campaign contributions.

As WW has previously reported, Scroggin, whom Fagan hired away from the city of Portland in 2021, pushed for Oregon to furnish similar information to the public here (“The Customer Is Always Right,” Jan. 4). Currently, it is available only via a public records request.

“We are an outlier in the lack of information we provide in this space,” Scroggin wrote in an email to her superiors Nov. 21, 2022. That email came after the Elections Division’s IT department had worked on a website of campaign finance violations for a year only to have Fagan’s management team repeatedly reject Scroggin’s pleas to let it go live. (Fagan forced Scroggin out in December, telling WW that Scroggin was insufficiently focused on “customer service.”)

Fagan says her goal in 2022 was simply to get through the primary and general elections smoothly. That, she says, rather than any aversion to transparency, is why the campaign finance violation website got placed on the back burner.

“Last year was the first major election since 2020 and the Jan. 6 insurrection,” Fagan says. “I was laser focused on making sure everything went smoothly, so I made a decision to not get distracted by new initiatives. Now that 2023 is here, I am excited to implement several new ideas, including more public education about campaign finance rules and a website proactively listing fines.”

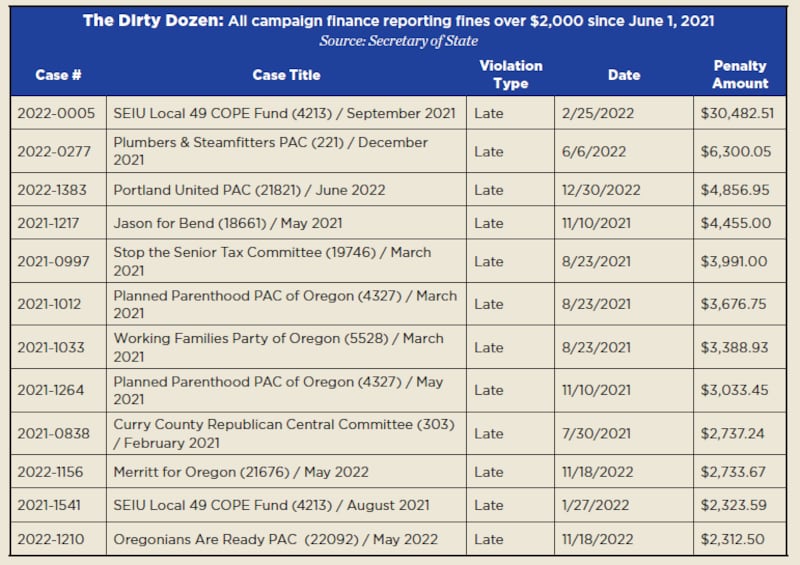

In the meantime, WW requested the fines for late or improper campaign finance filings since June 1, 2021, when Scroggin began working full time. There are about 440 of them. The chart below shows the largest—the 12 fines for more than $2,000 each. (In every case, the fine was issued because a transaction was reported late.)

Fagan, a Democrat, insists the delay in making the website live had nothing to do with protecting special interests. “The largest fines issued under my administration were to some of my political allies,” Fagan says. “These fines show that Oregonians can trust me to apply the rules fairly and equally to everyone.”

The largest fines are nonpartisan, with both Fagan’s biggest supporter (Service Employee International Union) and the political arm of the former employer of her chief of staff, Emily McClain (Planned Parenthood), represented, along with conservative (Stop the Senior Tax) and moderate PACs (Portland United and Oregonians Are Ready).

Scroggin says the political diversity of the groups fined shows her team was doing its job objectively: “The records and the fines speak for themselves, and the professional, nonpartisan nature of the Elections Division.”