John Welsh, a 46-year-old father of two, moved to Portland a year ago, and he has a message for the thousands of people fleeing because crime and blight make the city feel unsafe: Try raising a transgender teenage daughter in Texas.

Welsh and his wife began to see that Portland was a better place for them when they came on a house-hunting trip in June 2021. They were out looking at properties, and their daughter, Ess, then 15, used her bus pass to go to the Japanese Garden from their Airbnb in Irvington.

“My wife said, ‘You know, that’s the first time in as long as I can remember that I’ve felt safe with her just going out and about somewhere,’” Welsh recalls.

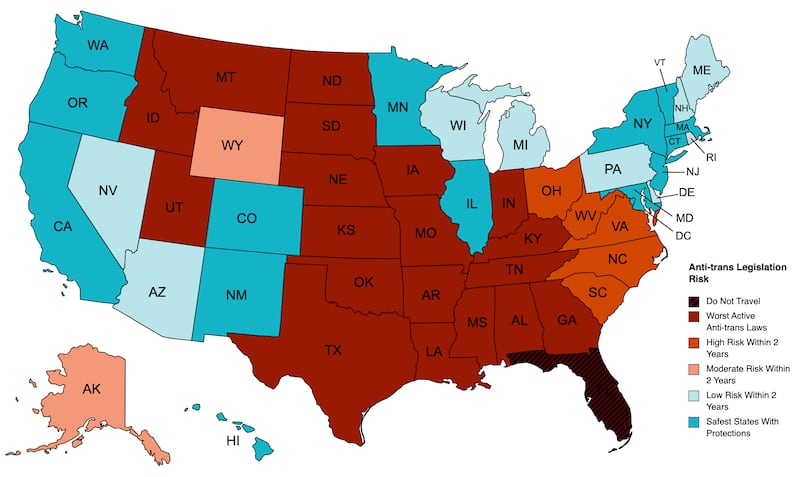

That feeling helped seal the deal. Welsh and his family joined thousands of others leaving Texas, Florida and other states that are waging a culture war on LGBTQ+ people, especially those who are transgender. Many of these gender refugees are moving to Oregon because of its tolerant laws and lifestyle.

The influx is welcome, especially in Portland, where well-documented factors (crime, taxes, remote work) have resulted in population declines for the first time in a generation. Multnomah County lost population in the three years ending in July 2022, according to Portland State University’s Population Research Center.

But tolerance—along with Mount Hood and great beer—could be the thing that keeps Portland vibrant.

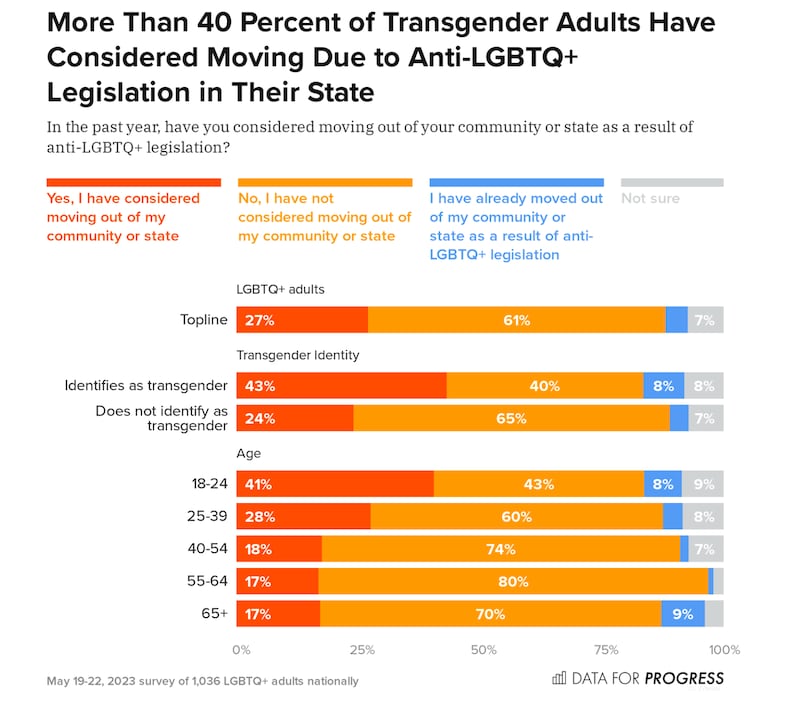

A June poll by left-wing think tank Data for Progress showed that 43% of transgender adults and 41% of young adults ages 18-24 have considered moving to escape anti-trans legislation. Some 8% of both groups have already moved, the poll says.

Transgender people account for 0.6% of the adult population, according to a recent Gallup poll. Combining the figures from Gallup and Data for Progress, Erin Reed, a queer-rights researcher who writes the influential Substack Erin in the Morning, estimates that as many as 260,000 trans people have already fled red states for blue ones and that another 1 million are considering it.

“Should this trend persist,” Reed writes on her Substack, “we may witness the largest domestic migration crisis since the Dust Bowl.”

Cue the Welsh family. They came to Stumptown from Round Rock, just outside of Austin, one of the fastest-growing cities in America. It may be Valhalla for guys like Elon Musk, but it’s hell if you’re trans, John Welsh says. When his daughter told the school she wanted to use the women’s bathroom, the anti-queer, book banning group Moms for Liberty started protesting at school board meetings.

“They didn’t call her out by name because they are not allowed to do that,” Welsh says. “But it was very clear that it was about her.”

Around the same time last year, Texas Gov. Greg Abbott ordered the Texas Department of Family and Protective Services to investigate for child abuse parents who approve gender-affirming care for their transgender children, including puberty-blocking drugs.

Welsh, his wife, Kristen, and Ess had seen enough. They packed up their car and left for Portland, leaving family and friends behind.

During the past month, WW spoke with families and individuals who made the same journey. If Portland is seeing an exodus of wealthy residents who are tired of high taxes that don’t seem to fix anything, it may soon become a haven for people who have seen what else government can do to its citizens: oppress them.

Here are their stories.

The Rodriguez Family - Fort Worth, Texas

Tiffany Rodriguez, 41, grew up in Texas and moved back to Fort Worth with her wife, Dana Ferrara Rodriguez, to be close to her extended family when she added a new member: Penelope, now age 6.

But after six years in San Diego, her home state felt dangerous for a lesbian couple. “In Texas, we couldn’t hold hands because you didn’t know what would happen,” Rodriguez says.

When her daughter was born, she and her wife worried that the clerk would go rogue and refuse to put them both on her birth certificate, even though it’s been required by law since 2015. Being surrounded by Trump flags didn’t exactly put her family at ease, either. “You knew that a majority of your neighbors voted against the safety of your family,” Rodriguez says.

Anti-trans legislation, combined with book bans (Texas topped the nation in the second half of 2022 with 438) and laws that allow most adults to carry guns without a permit, convinced Rodriguez it was time to shop for a new home.

She was working remotely for the American College of Healthcare Sciences in Portland, so Stumptown made sense. They visited, fell in love with Sellwood, and bought a house in May.

She and her family couldn’t be happier, Rodriquez says. Most stores in Sellwood have Pride signs, making them feel safe on walks. Another plus: the Portland Thorns.

“In my 40 years of life, I had never seen both men and women root for a women’s sports team,” Rodriguez says. “We went from feeling tolerated in Texas to feeling welcomed.”

Even a move to paradise has downsides, though. Rodriguez misses her parents, her brother, and her four nephews. Penelope films a YouTube diary for them every day to stay in touch.

The Krajcer Family - Austin, Texas

Before Karen Krajcer left Texas, she raised a little hell for trans rights and for her daughter Jessie, 11. She chanted at rallies. She testified before the Texas Legislature in Austin, where she lived.

It’s not hyperbolic to describe Texas as a dystopia for trans people, Krajcer, 44, says. Gov. Greg Abbott’s executive order to investigate parents for approving gender-affirming care meant she and her husband could be charged with child abuse for getting Jessie hormone treatments that, according to scientific studies, alleviate suicidal ideation in trans adolescents.

“Child Protective Services could throw me and my husband in jail,” Krajcer says. “Every time I say it, I hear how ludicrous it sounds. But this is the reality that is happening in our time. What would you do if your state was depriving your children of best-practice, lifesaving health care, and the penalty is that the state can put you in jail?”

The hypocrisy was unbearable for Krajcer. Hormones have been used for decades to block precocious puberty in cisgendered people, including a member of her own extended family.

In an article for The Nation, Krajcer described creating a “safe folder” for CPS investigators that contained, among other things, a letter from Jessie’s pediatrician confirming her gender identity and proof of annual wellness checks, and another letter from her pediatric neurologist describing how gender dysphoria had harmed her mental health.

Abbott went further in June, signing a bill to ban hormone treatments and surgeries for transgender minors, but the Krajcer family was already gone—to Portland.

“We’re gender refugees,” Krajcer says.

The move was hard and costly, she adds, but it was worth it. Krajcer even got to testify before the Oregon Legislature in favor of House Bill 2002, which, among other good things, requires Medicaid and private insurers to cover some gender-affirming surgeries.

“I knew we would feel safer in Portland,” Krajcer says, “but I didn’t know we would be this happy.”

Carolyn Ward - Lexington, Kentucky

For trans people, there are many cities in Kentucky worse than Lexington. It’s a college town, home to the University of Kentucky, so folks there are more tolerant.

But state laws apply to all cities, and Carolyn Ward didn’t want to wait around to see what would come once Democratic Gov. Andy Beshear was no longer in office in an overwhelmingly Republican state.

Ward, 28, had a lot to lose. She came out as trans in December 2019 and started hormone replacement therapy the following April. The treatment rescued her from debilitating depression. She and a friend (like a sister to her) heard good things about health care for trans people in Oregon, and they began plotting a move.

Ward got a job at Krispy Kreme and saved $5,000 by living with her parents—a privilege, she says, many trans people don’t have. They wanted to move to Portland, but it was too expensive, so they opted for another college town: Eugene. They arrived in November 2021, stayed in a Motel 6 for a month, then hopped from an RV rental to a studio apartment to a one-bedroom.

Despite all the moves, the odyssey has been worth it, Ward says. A doctor here doubled her dosage of estrogen and progesterone, and she feels much safer, to boot.

“In Kentucky, there was a risk that I would be clocked,” Ward says, meaning she’d be identified as trans when she didn’t want to be. “In Eugene, trans people are much more normalized.”

Ward’s move was prescient. In March, the Kentucky Legislature overrode a veto by Gov. Beshear to pass one of the most punitive anti-trans bills in the country. It prohibits conversations about gender identity in schools, forbids trans students from using the bathroom that matches their gender, and bans all gender-affirming medical care for trans youth.

“I left a bit preemptively,” Ward says. “Rather than leave when the flames were consuming the room, I left when I smelled smoke.”

Some good news: Late last month, a federal judge in Kentucky temporarily blocked the law from taking effect while other courts hear challenges.

Jesse C. - Neosho, Missouri

As a trans person, Jesse C. had a lot to leave behind in Neosho (pop. 12,700).

The state is among the most conservative in the nation, and his divorced mother belonged to an evangelical sect founded by Harold Camping, a Christian radio broadcaster who proclaimed the world would end in fire and brimstone in 1994 (later amended to 2011).

Jesse, 27, lived under the specter of Apocalypse for years and thought Camping might be right when a milewide tornado ripped through nearby Joplin—in 2011, no less—and killed 158 people. After 2011 came and went (and Camping died in 2013 with the world still turning), Jesse had decisions to make.

“I grew up believing I wouldn’t make it to adulthood because the world was going to end,” says Jesse, who goes by he/she and her/him pronouns interchangeably.

He had always felt some gender dysphoria, and it became acute when he began menstruating. He wiggled his way into some “not quite trans-specific care” in Missouri and got birth control that eliminated his period. But that wasn’t enough. He finished college, and when he didn’t get into graduate schools that he wanted, he began eyeing Portland.

“I grew up viscerally aware that my existence would’ve been illegal if I had been born a decade earlier,” Jesse says. “In communities like that, the Portland area is one of the places you go.”

The economy was better here, too, he says. In Missouri, he made $8.16 an hour working in a youth shelter, a little more than half of Portland’s $13.25 minimum wage at the time.

Budget conscious, Jesse got his name changed in Missouri, where it was cheaper. Then, in August 2020, Jesse and his partner at the time loaded up a U-Haul, hitched his Volvo sedan to the back, and headed west for a “long and harrowing” trip across the country. Their rig drank gas in the Rockies. They ran out of money in the Cascades and had to call a friend.

COVID was raging when they arrived, but Jesse managed to get a job at a youth shelter in Vancouver, Wash. He got transferred to a queer-specific shelter in Portland and now lives in unincorporated Clackamas County.

“I’m still way more comfortable with country life than city life,” Jesse says.

The Portland area is the refuge he expected, he says. He’s got a gender therapist and health insurance, things he lacked back in Missouri.

“All the cool things I had been reading about in Portland for forever are just things that my friends and I can do,” Jesse says. “The feeling is, holy shit, this is real.”

See more of Willamette Week’s Pride 2023 coverage here!

Correction: The original version of this story said that Karen Krajcer’s sister had taken blockers for precocious puberty. It was a member of her extended family who had. WW regets the error.