Metro, the three-county regional government, would face a “challenging path” if it goes back to voters with a measure to extend its supportive housing services tax on high earners to 2050 from 2030, when it is set to expire, according to new polling results.

Metro has been debating such a measure for more than a year, aiming first for the May ballot and now for the November one. Among the features being discussed are the extension and a plan to index the tax to inflation so that middle-income payers don’t get swept up in a levy designed to hit only the wealthy.

“Voters continue to back the idea of pairing affordable housing and supportive services, and view most of the measure’s investments as important priorities,” pollsters at FM3 Research wrote. “At the same time, continued ambivalence about the performance of local government in these areas provides a headwind that limits the breadth of voter support.”

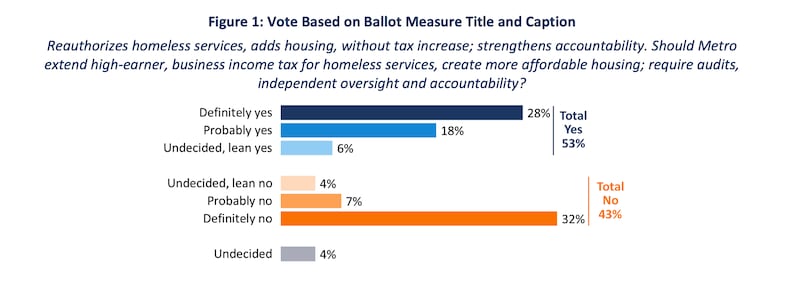

Based on a title and brief caption alone, 53% of voters said they would vote yes on the measure. That includes 28% who would would “definitely” vote yes, 18% who said they would “probably” vote yes, and 6% who were undecided but leaning yes.

As for the detractors, 32% said they would “definitely” vote no, while 7% said they would “probably” vote against it, and 4% were leaning toward no.

Holding back support is skepticism about county government, especially in Multnomah County, the pollsters said. Metro passes the proceeds along to Clackamas, Multnomah and Washington counties, which spend it as they see fit.

“Attitudes toward local government vary by county, with 29% of Multnomah County voters having a favorable view of their county government, compared to 62% in Clackamas County, and 51% in Washington County,” pollsters wrote.

The results reflect a similarly weak appetite pollsters found last month for doubling the city’s Parks Levy. In Metro’s case, the polling numbers offer as many questions as answers.

“The measure is absolutely viable,” said Christian Gaston, who has been consulting with Metro on housing for the past year. “The question is what kind of campaign you need” and whether opponents would show up to fight it.

At first, Metro considered asking voters for a property tax levy to pay for a new housing bond, Gaston said. When that idea polled poorly, Metro began considering changes to the SHS tax, including one that would allow counties to use some of the money to build or buy housing. As it stands, the money can only be used for services, such as rent assistance vouchers.

A spokeswoman said Metro is still considering whether to seek passage of a measure in November. Last week, Metro’s seven-member governing council said it will consider an ordinance that would index the tax to inflation. Metro will seek testimony on the ordinance June 17.

As it stands, single payers owe the 1% tax on income above $125,000, and married filers owe it on income above $200,000. But inflation can push incomes up without increasing buying power as costs rise along with incomes. With indexing, the thresholds would rise each year, depending on the inflation rate. In the first year, say, the new thresholds might be $127,500 and $204,000.

The best news for supporters of the SHS tax: About 50% of voters feel the Portland region is on the wrong track, while 33% see it as headed in the right direction. That’s an improvement compared with wrong-track numbers as high as 78% in 2022 and 2023, the pollsters said.