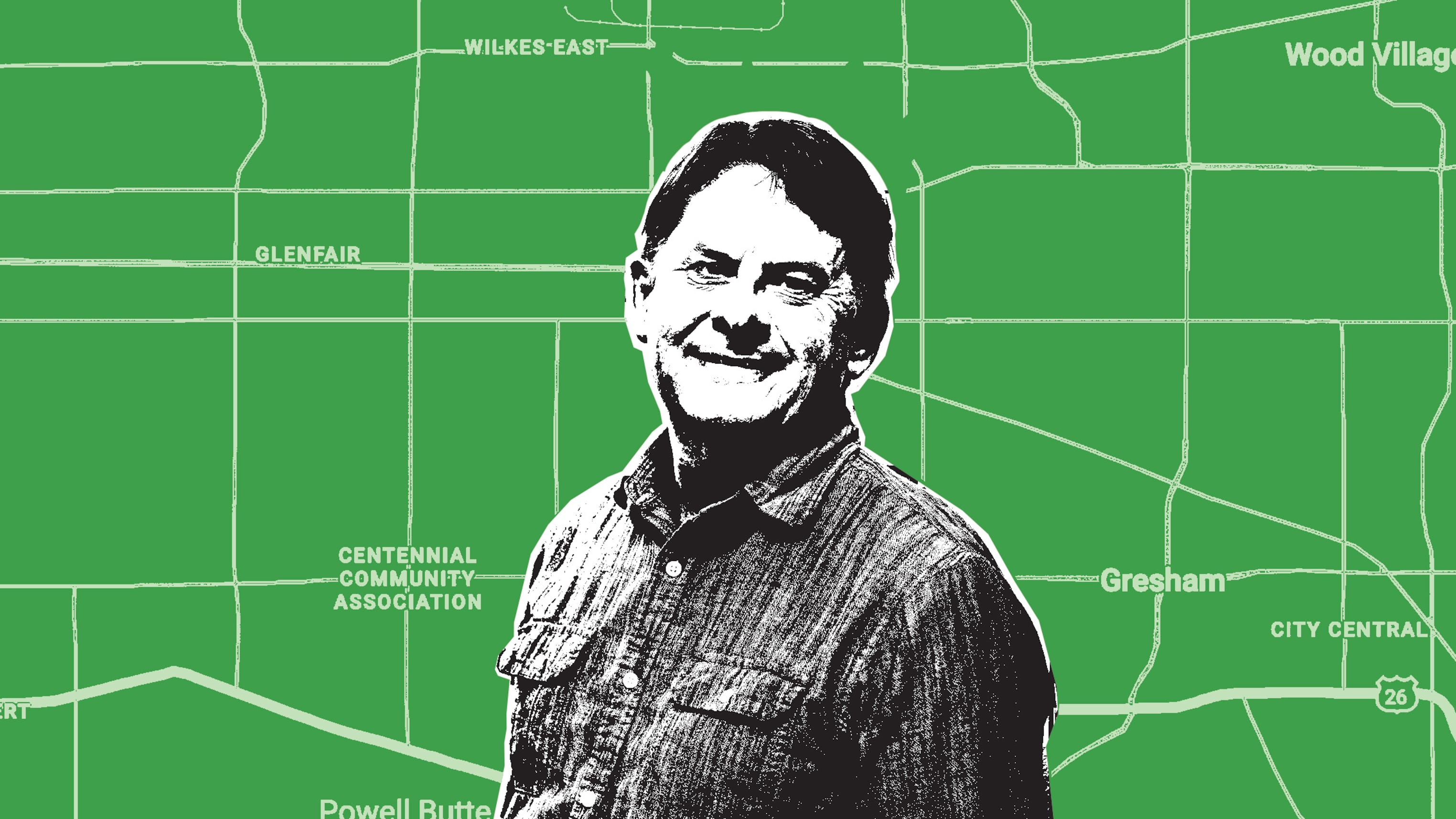

ROCKWOOD DEVELOPMENT SCRAPPED: Brad Ketch, the former tech executive turned nonprofit director who once ran Multnomah County’s largest family shelter, has halted plans to build 56 units of affordable housing in the Rockwood section of Gresham, one of the poorest neighborhoods in the metro area. After submitting 66 planning documents and spending $73,425.76 on fees, East County Housing LLC, an entity controlled by Ketch, emailed the city of Gresham on Jan. 7 to withdraw its application during design review of the $7.9 million project, called Ash & Pine Multifamily, according to city records. East County withdrew from the process after the owners of a property next door appealed the project’s approval, arguing that it required a traffic analysis, which East County Housing hadn’t done. Nor did East County submit a statement showing how it would conform to affordable housing rules, the appellants wrote. The matter was scheduled to go before the Gresham City Council on Jan. 20, but East County withdrew its application, mooting the appeal. The withdrawal comes as Ketch suffers setbacks in other ventures. Last June, Multnomah County halted rent payments and pulled homeless families from East County Housing’s Rockwood Tower, a former Best Western hotel that Ketch purchased in May 2021 with a $6.8 million grant of state funds. The county alleged that East County had billed it for empty rooms and charged inflated prices for maintenance, allegations that Ketch denied. Ketch didn’t return an email seeking comment on why East County Housing abandoned the project. To restart it, Ketch would have to resubmit all the documents, Gresham spokesman Nate Jones says, because the old one is “now nullified with the withdrawal.”

DEMOTION OF PRIMARY CARE CHAMPION RAISES CONCERNS AT OHSU: Internal emails show that Oregon Health & Science University is removing the chair of the Department of Family Medicine, an abrupt shakeup at one of the medical center’s largest and most public-facing programs. Dr. Jennifer DeVoe has served as its chair for a decade, overseeing primary care services, education and research of more than 200 faculty members and numerous residents at the school’s main Portland campus and many clinics beyond. After holding a hastily arranged meeting with leaders in the department, Dr. Nathan Selden, the dean of the OHSU School of Medicine, told staff in a Jan. 9 email that DeVoe would “complete her service as chair” effective Feb. 1, and that he would appoint an interim replacement soon. In her own email to the department two days later, DeVoe said it was Selden’s decision to end her tenure as chair, but noted that her other work at OHSU, including as the director of its Center for Primary Care Research and Innovation, would continue. Still, the news—and lack of explanation or immediate succession plan—left many faculty members concerned. Four, who spoke with WW on condition of anonymity, describe DeVoe as a popular leader and a force for primary care and population health research in an institution that tends to prize the financial returns and cachet associated with specialized tertiary and quaternary care. Selden has been a neurosurgeon at OHSU since 2000, but he’s relatively new to the dean job, to which then-president Dr. Danny Jacobs appointed him in 2024. DeVoe and Selden both offered no comment to WW; an OHSU spokesperson said the university continues to strongly support primary care.

PPS MANDATES CHRONIC ABSENTEEISM REFORMS: Portland Public Schools officials are making a concerted effort to improve the district’s attendance rate. Last winter, PPS officials sourced student-level data to better understand what brings students to school, and weighed those responses against national data to build recommendations to improve attendance. Results showed students were more motivated to attend school often if they had access to engaging education and felt a sense of belonging. The district is tackling engagement in the classroom as part of literacy and math goals, so its central attendance team has focused on teaching students about emotional regulation, improving teacher-student relationships, and boosting school safety. (This year’s student survey saw a spike in students saying they don’t go to school because they’re worried about safety.) District officials have mandated staff across its schools to form data teams to examine the specific reasons their students feel compelled to attend class. Those teams also intervene in cases of chronic or severe absenteeism (missing between 50% and 79% of school) and monitor the progress of new help for those students. Naomi Orem, the district’s lead on attendance work, told School Board members at a Jan. 8 meeting that the district is already seeing some payoff. As of Dec. 19, PPS reported 74.24% of students were regular attenders, up 2.3% districtwide. The district has also seen improvements among all of its five focal groups: Black students, Native students, students in poverty, special education students, and multilingual learners.

MONKEY TOO BIG TO FAIL? Closing the Oregon National Primate Research Center, as Gov. Tina Kotek and some legislators would like, would cost at least $118 million, according to Oregon Health & Science University, which runs the Hillsboro facility. To meet that low-end estimate, OHSU would complete current research grants and shrink the center over a period of eight years, according to a study the university commissioned in response to legislators’ calls for closure. Shutting the facility immediately and sending 4,793 nonhuman primates to other sites would cost $241 million, according to the study. The most expensive option, converting the ONPRC into a monkey sanctuary, would cost between $220 million and $291 million in the first eight years, with expenses continuing beyond that. The cheapest alternative, according to Huron Consulting Group, the primate experts hired by OHSU, would be to keep the center open at a smaller scale. That option would cost between $50 million and $70 million over eight years. The ONPRC is under dual threat from the Trump administration, which is curtailing funding for research that uses animals for medical testing, and animal rights advocates who last year captured the ears of lawmakers with a radio and television campaign showing grim conditions at the the center. ONPRC, which runs a deficit because of high labor costs and insufficient funding, gets about $56 million a year from the National Institutes of Health, one of the agencies under threat by Trump. Kathy Guillermo, senior vice president at People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals, one of the center’s loudest critics, savaged the report, calling it a “piece of nonsense apparently written by experimenters hoping to keep the violation-ridden primate center in business” and a “financial fantasy plan in which closing the fiscally unsound primate center would cost more than building a new hospital for Oregonians.”

GIVE!GUIDE RECAP COMING SOON: A team of third-party CPAs are conducting a meticulous review of the $9.26 million raised by Give!Guide to ensure the generosity is properly accounted for. Look for a detailed breakdown of your donations in next week’s edition.