Last year, Oregon Health & Science University released a report it had commissioned to assess its handling of a sexual misconduct case. In the school’s words, the 86-page “Schneider report,” produced by the outside lawyer Scott Schneider at a cost of $165,456, reviewed “the processes, policies and actions taken or not taken by relevant leadership involved in the Dan Marks matter.”

The Dan Marks matter was the case of a longtime physician and professor whom OHSU forced out more than a year after receiving a photo that showed him holding a school-issued iPhone under the table, its camera turned on, in the direction of two female students wearing skirts.

Schneider found in April 2024 that the school had handled the Dan Marks matter quite poorly—one in a series of HR mishaps that preceded the departure of then-university president Dr. Danny Jacobs.

The institution vowed to take all of Schneider’s advice for reform, such that it would not fail in this way again. “OHSU has implemented the recommendations of the Schneider report and invested significant resources and changes to ensure that sexual harassment is appropriately reported and addressed,” a spokesperson says in an email.

That has been OHSU’s public-facing stance. Over the past year in court, however, the institution has established some notable distance between its own account of the Marks saga and that of the report it commissioned.

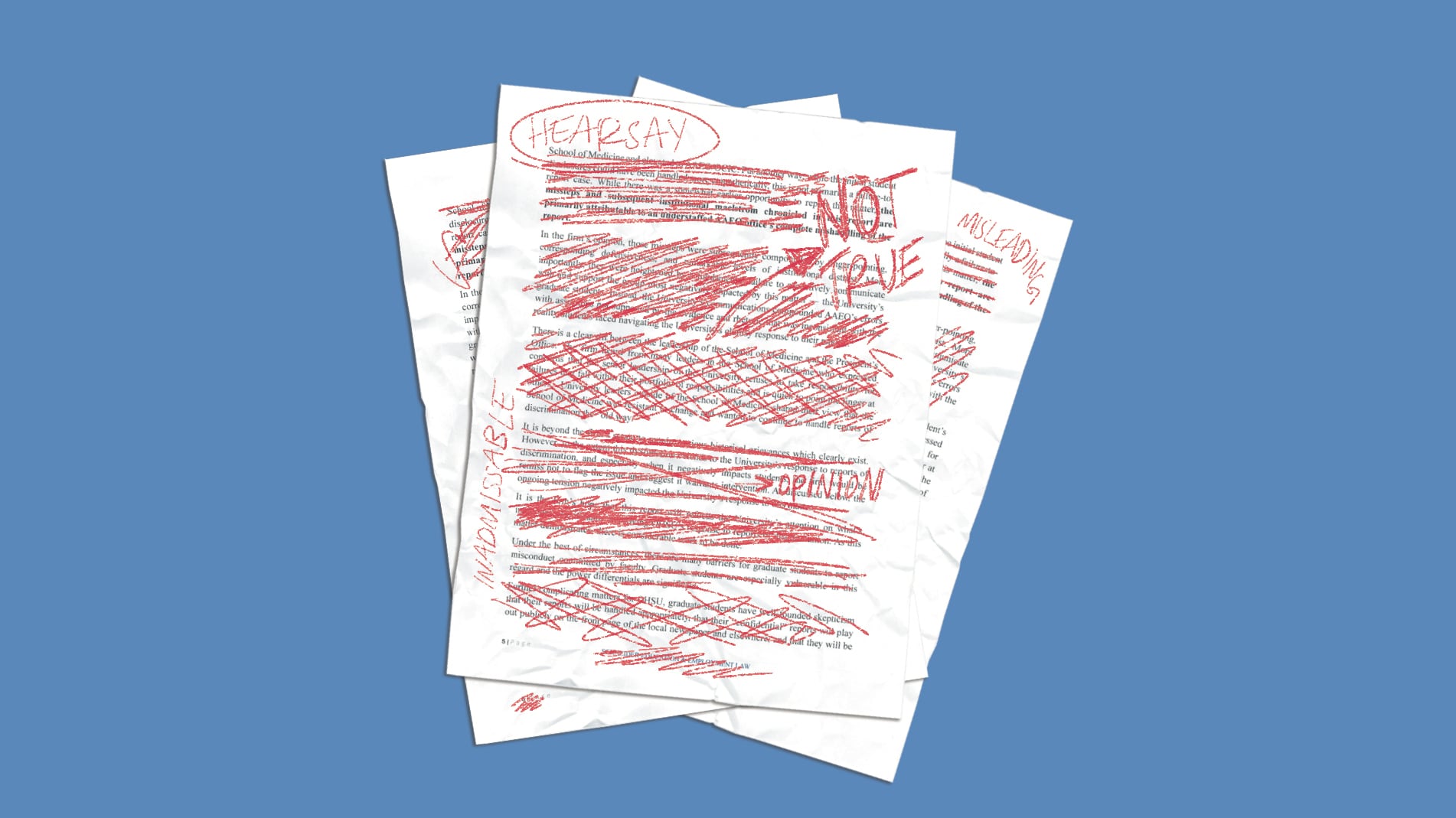

The Schneider report is “an investigative document that is rife with gratuitous facts and opinions,” said one brief filed by OHSU earlier this year. Referring to a disputed matter in which the school’s narrative diverges from that of the report, the school wrote, “Mr. Schneider’s opinion is just that—his opinion.”

The context, of course, is that the school was being sued. Seeking $6.2 million in damages, the plaintiff, former OHSU School of Medicine dean Dr. David Jacoby, alleged late last year in Multnomah County Circuit Court that the school defamed him during the Marks affair, lying to make him a scapegoat for its own institutional failings, and retaliating when he spoke out.

Jacoby’s attorney in this case, Paul Buchanan, says it’s shocking that OHSU would hire a reputable Title IX expert, have him conduct this extensive investigation, and then argue some of his conclusions were wrong.

“I think that’s really disappointing that they are continuing to double down on the lies that their own investigator called them out upon,” Buchanan tells WW. “I think it’s preposterous.”

To be sure, the legal strategy has worked well for OHSU. On April 30, Multnomah County Circuit Judge Chanpone P. Sinlapasai dismissed Jacoby’s lawsuit and ordered him to pay the university’s legal fees.

But OHSU’s approach also raises questions about what the university—Portland’s largest employer—took away from a report it commissioned in part as a demonstration to its workers and students that it was prepared to take responsibility for its failures. It’s also an example of how, for many institutions, a fact-finding impulse can be little match for the imperative to defend themselves in court.

Asked to explain to a layperson why the school would argue that a report that it itself commissioned and publicized is rife with gratuitous facts and opinions, full of hearsay, and inappropriate to be used as evidence in a court of law, the university said in a statement that Jacoby’s claims were without merit: “OHSU defended itself, and believes the court reached the right result.”

Jacoby, according to the Schneider report, could have shown more prudence during the Marks matter. But the ex-dean cited the report in his suit because it ultimately sided with him on key points—namely that the school issued “misleading statements” about his role in a maelstrom that, at base, was attributable primarily to an understaffed university investigative office’s “complete mishandling” of the matter. It was counterproductive, Schneider added, for OHSU to blame others when that office failed.

OHSU acknowledged in court filings that its initial institutional investigation of the Marks matter was “insufficient.” But, though the school says no one person is to blame, it has generally used the legal venue to attack Jacoby—a response, it says, to the plaintiff’s decision to cast himself as the victim instead of taking responsibility for his role in a crisis that occurred on his watch.

In an email to WW, the school describes Jacoby’s suit as “a public and legal attack intended to punish OHSU for being transparent with the OHSU community about the Marks controversy.” In court, it has argued that its top officials, in order to be able to freely discuss matters of public concern, have an “absolute privilege” that renders them immune from defamation claims like Jacoby’s. (Such reasoning would effectively allow top officials to lie with impunity, Buchanan says, and should be “shocking to Oregonians.”)

Downplaying the Schneider report became, in OHSU’s court filings, a kind of refrain. “Defendant objects to this request because it assumes facts not in evidence, and because it seeks an admission based on the Schneider report, which is inadmissible evidence and hearsay,” it said, again and again, in its earliest response to the suit in December last year.

The question of what evidence should be admissible in court is in some ways a subtle one. In a phone interview, Jeremy James, a Portland trial lawyer unconnected to the suit, said courts are wary of “prejudicial” forms of evidence—for example, information which, if admitted, might induce members of a jury to outsource their judgment to, say, an expert investigator who had already reviewed the case.

“Without knowing the details here, in general, it makes sense that OHSU would raise admissibility issues about every single piece of evidence that the plaintiff presents,” James says.

Still, OHSU’s legal strategy goes further. Regarding at least one sequence of events, for example, the school seems to outright contradict Schneider’s account.

The dispute is about who was responsible for the $46,000 award Dr. Marks received as he was resigning from the school. News of the bonus turned out to be a public relations debacle, and the culpability question is important to Jacoby’s defamation claim. This is because in internal communications and statements to the press, OHSU administrators suggested that the bonus was issued at his discretion. Jacoby says it was not.

Schneider, for his part, did not seem to find the matter particularly complicated. “The decision to provide Dr. Marks the Presidential Recognition Award is perhaps the most straightforward issue assessed by this review,” he wrote.

His account, based on emails and other records, is this: In a rushed manner, the school issued the award, untethered to performance, to a wide array of managers and faculty members. Though it had completed its report of Dr. Marks’ alleged wrongdoing, OHSU’s guidelines left him eligible for the bonus—an outcome top officials appeared to acknowledge and sign off on without Jacoby’s involvement. “Subsequent attempts to blame Dr. Jacoby for this are, at best, misleading,” Schneider wrote.

In court, OHSU has continued to blame Jacoby. In sworn declarations that seem designed to explain away Schneider’s conclusions to the contrary, top administrators emphasized Jacoby’s discretion in the matter. Notably, the school cited then-HR director Qiana Williams’ claim—which Jacoby denies—that she explicitly discussed the matter with him in a meeting. (Schneider, citing email and video-record evidence, found Williams’ account of events “implausible.” She left the school last year.)

Ultimately, OHSU prevailed in the case through a powerful legal maneuver that allows parties to quickly get frivolous suits tossed out when someone is trying to silence them on, say, a matter of public interest. The university argued that fending off Jacoby’s suit was a textbook application of Oregon’s anti-SLAPP statute, which governs the maneuver. Buchanan countered that the school was seeking to use the law in direct inversion of its purpose.

For the parties, stakes were high. Typically, lawsuits can be pursued on the basis of a plaintiff’s good-faith belief that a set of claims are true, since typically, defendants have most of the evidence, which a plaintiff cannot fully access until the discovery process later in litigation. If certain conditions are met, the anti-SLAPP motion shifts the burden to plaintiffs to marshal their evidence up front and show they would likely win on that basis.

It is unclear what arguments moved Sinlapasai to grant OHSU’s motion; the judge’s written decision did not offer any reasoning. Buchanan says the unexplained decision “feels arbitrary at best,” and he and his client have appealed—a process that could take somewhere between weeks and years. In the meantime, the precise amount Jacoby owes OHSU, where he continues to work as a professor, was in recent days still being litigated.

OHSU seeks from him more than $250,000 in legal fees. Buchanan describes this as “extremely excessive.” In court, he said OHSU offered to “forgive” Jacoby half of the sum after two years—if, in that time, the professor dropped his appeal and did not issue statements on the matter. He said Jacoby declined the offer.

This reporting is supported by the Heatherington Foundation for Innovation and Education in Health Care.