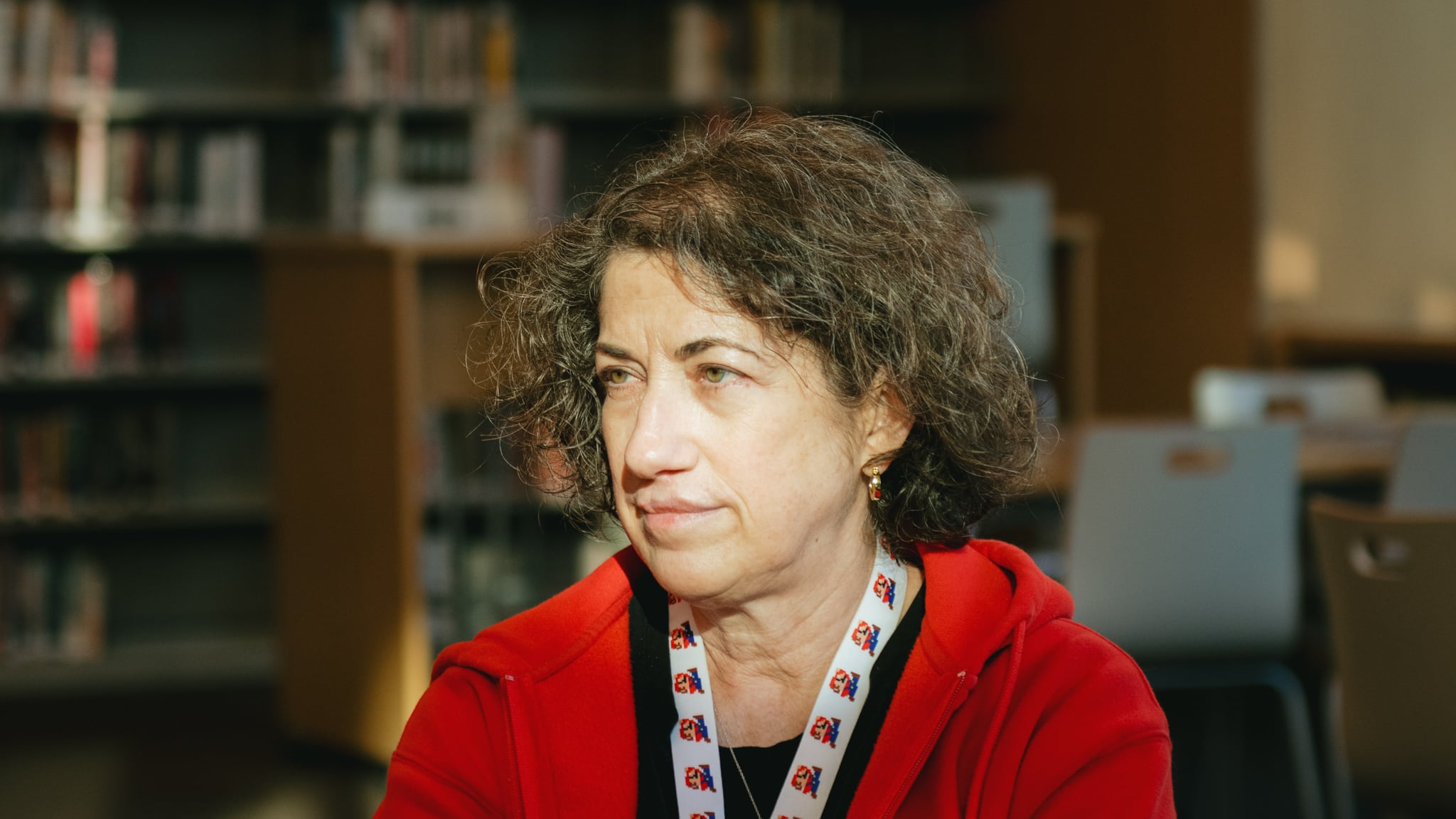

As the school librarian at Lincoln High School, Lori Lieberman has tried many tactics to make reading fun.

Lieberman created a romance book club. (It attracts dozens of students to its monthly lunch meetings.) She has an endless reading list so she can find students a book that’s their perfect match, a responsibility she says she takes “very seriously.” And she works hard to make her library a warm and inviting space—a mid-October tour included a trivia contest for a big candy jar, among other whimsical decorations.

But up until this academic year, Lieberman had big competition for her students’ attention: cellphones.

The library had a box where students were meant to slip their phones, but she says many kids didn’t do that. When Portland Public Schools issued a new policy on cellphones last January, asking students to keep them “off and away” for the duration of the school day, she heard grumblings from students who couldn’t bear the thought of parting with their screens. “I would just smile and be like, um, it’s happening,” she recalls with a chuckle.

This fall, the phones went into Yondr pouches at Lincoln. And then something unexpected happened.

“I could see that there were more kids coming in checking out books. There are always classes that come in…but this was kids just coming in on their own, and lots of kids who are not regular library patrons,” says Lieberman, who notes circulation rates at Lincoln are up 55% since the start of the school year.

It’s the first year in which students across Oregon can’t reach for their phones anymore. Faced with concerns about student mental health and disengagement from learning, states and school districts nationwide zoomed in on how to control phone usage in the past academic year. In July, Gov. Tina Kotek issued an executive order limiting student cellphone use statewide.

Soon, school librarians nationwide started noticing a compelling trend. As cellphone bans went into effect, Newsweek reported, school districts big and small reported an uptick in library circulations. That made waves at a monthly meetup of librarians that PPS teacher-librarian Julie McMillan attends. Following that meeting, she raced back to work to confirm whether the trend was happening here, too.

It was. PPS library circulations have increased by 15% so far this fall semester, from 87,540 to 100,886. (The district, on average, circulates library books about 1.07 million times a year.) “It was a welcome surprise that came about,” McMillan says.

Logan Ferrua, a senior at Lincoln, says he’s never really read for fun until this year, but now he makes an effort to read at least 30 minutes a day. He says he’s noticed the phenomenon in action. “In the past, people normally go on their phones when they’re done with work,” he says. “Now that we can’t, I have noticed a lot more people reading books in classrooms when they have free time.”

There’s not one genre that’s trumping all others across PPS schools. In the K–5 grades, McMillan says circulation data has indicated interest in Jeff Kinney’s timeless Diary of a Wimpy Kid series and Dav Pilkey’s canine cop graphic novel Dog Man. Popular categories that PPS high school librarians reported flying off the shelves included fantasy, manga, and politics and government.

Those choices reflect what McMillan says are larger trends during these times—journals and papers she’s read recently indicate kids are gravitating both toward joyous escapism and books that help them better understand the political landscape.

Reading books can also expose young students to stories that they wouldn’t see in their own communities, McMillan says, fostering social and emotional skills. “It builds empathy. It builds curiosity,” she says. “It really engages us in wanting to understand other people’s perspectives, and that hopefully leads to us working together differently.”

Dr. Ellen Stevenson, a professor of pediatrics at Oregon Health & Science University and Doernbecher Children’s Hospital, says literacy is “highly correlated” to positive health outcomes. “Reading is one of the best things you can do to help your child thrive,” she says.

That conversation has only amplified as technology has advanced, Stevenson says. A group of researchers at Seattle Children’s Hospital in April found that teens aged 13–18 spent about one and a half hours of a six-and-a-half-hour school day on their phones, and other studies have affirmed that students spend countless hours on phones outside of the school day. This can result in a phenomenon called “crowding out,” Stevenson says, in which phone use prevents kids from engaging more regularly in physical activity, recreation, and even sleep.

“If we can get kids not to be on their phones or screens, then that increases the opportunities for them to spend more time on connecting with other people and interacting meaningfully,” Stevenson says. “I think [kids checking out more books] is very exciting.”

Oregon could use any boost it can get. In the latest batch of Oregon Statewide Assessment System data, the state reported just 43% of its students as proficient in English and language arts.

Stevenson’s work concentrates primarily on the earliest readers, from birth through age 5, with the hope that engaging families early on will set kids up for success in school. It’s a hope that doesn’t always hold up to reality: Anecdotally, McMillan says kids tend to have a “voracious” reader phase through elementary school, which tends to slope down during middle school years, when many kids lose the drive to read outside of class assignments.

Lieberman, who’s worked across grade levels as a school librarian (this is her eighth year at Lincoln), says high schoolers are often overwhelmed with other commitments and with addictive social media. She says certified librarians, who are authorized to teach, often have one of the best chances to help reignite a love for reading in students. (Amid budget cuts, PPS has eliminated many full-time certified librarians out of elementary and middle schools. Recent data from an Oregon Association of School Libraries report indicates dozens of districts in the state don’t even have one.)

“Every couple of weeks, I have at least one kid who comes to me and they’re like, ‘You know, I haven’t read a book in a really long time. Can you recommend something to me?’” she says. “When that happens, I take that so seriously because I feel like I have one shot and I don’t want to screw it up. I really ask a lot of questions, and I really want to get something that’s going to hit out of the park.”

Ferrua’s current read is Graham Hancock’s Fingerprints of the Gods. He says he’s taken a big interest in books at the intersection of philosophy and history. “Lori’s helped me find a mix of those books,” he says, adding that he’s already seen the benefits of reading more for his day-to-day thinking.

“I question things a lot more now,” he says. “There are always multiple sides to a story, and it’s very important to gather those multiple sides from the story to really accumulate an honest opinion, from a historical point of view [as to] what really happened.”