The sand is hard at the water’s edge. South of Florence, on the Oregon Coast, you can walk the beach for miles and barely leave an imprint. Dig holes, build castles, turn somersaults, your meager indentations are soon scrubbed flat by tide and time. If you ever suffered an existential freak-out in philosophy class and started to doubt whether anything is real, this sand is a place to plant your flag. It’s massive, gritty, and solid. It sure ain’t going anywhere.

Do not be deceived, outlander. The sand is lying to you.

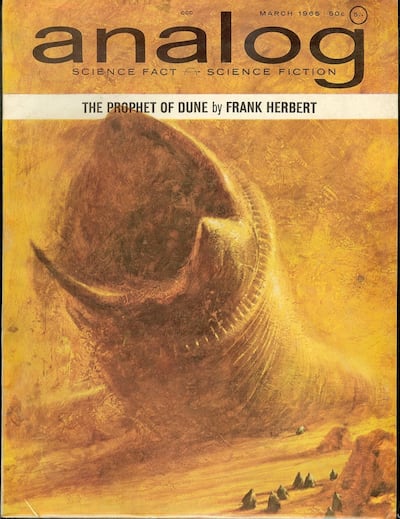

Back in 1957, an obscure freelance writer got an assignment from a San Francisco magazine to write about the Oregon Dunes, which for decades had been slowly drifting north and threatening to bury the town of Florence. To stop the drift, the federal government introduced beach grass and other species. The writer drove to Florence to document the community’s desperate struggle against the moving mountains.

He chartered a two-seater airplane to get a better look at the situation. At eye level, dunes appear solid, but high in the air, the writer saw ripples, curls and waves. Zoom out far enough, and dunes look fluid. They swell, they roll, they surge. But they do it all on a geological time scale.

The dunes are an ocean of sand, frozen in time.

This idea blew this writer’s mind. His healthy curiosity about sand morphed into a fanatical obsession. People edged away from him at parties. He delved so deeply into desert ecology, folklore, and the spiritual significance that he never finished the magazine article. Instead, the writer, Frank Herbert, spent the next seven years writing the epic novel Dune.

Today the fantastic landscape around the Oregon Dunes National Recreation Area offers hiking, horseback riding, bird-watching, sandboarding, dune buggies, paddling, swimming, and sundry sandy activities. You may also find what Herbert found—an otherworldly domain where the wind sculpts infinitesimal grains of quartz into monumental shapes, the laws of gravity are suspended, and time is bent into a pretzel.

Helter-skelter

Heading south on Highway 101, you will spy a veritable pyramid of sand towering over the mouth of the Siuslaw River at Florence, which marks the northern edge of the dunes. A good place to begin your odyssey is at the Oregon Dunes Loop Trail (Highway 101 near milepost 201), a couple of miles south of Dunes City. A short trail opens up to an exhilarating slope of sand tempting grown adults to dash down helter-skelter, screaming at the top of their lungs. The ocean’s mumble grows more insistent as the path wends through pond and stream until you reach the shore, where Pacific breakers crash in endless succession. Here the sand is studded with shells and pecked-over sand dollars. A pelican glides along the foredunes, its neck coiled like a whip, its feathers grazing the beach grass.

The going gets harder on the way back. The trail twists through scarps and turrets, and you may sink to the ankles in sand. Dune connoisseurs suggest wearing “active sandals” (sneakers will fill with sand) and taking turns going single file—it’s easier to follow in someone else’s footsteps. (Not a metaphor—a hiking tip.) You may spot a bald eagle taking a bird bath in a lazy ribbon of stream. The creatures are impressive, but if you want to see monsters, keep going.

Stalking the dunes

The Oregon Dunes are the biggest coastal dunes in North America, stretching more than 40 miles from the Coos River to the Siuslaw River. They comprise about 30,000 acres and reach as high as 500 feet. But the small sign for the John Dellenback Trail, a few miles south of Reedsport, gives little hint of the marvel to come.

The trail starts full of bracken and mud. The air is clear, cool, and strangely still. The piccolo of distant birdsong is answered by the meandering bassoon of a bumblebee drowsing through the wildflowers. As you hike west, toward the theoretical ocean, the trail climbs and the dirt gives way to sand run through with sharp blades of beach grass. The path is strewn with clumps of red fescue. Then the trees thin out and, with a few more steps—kull wahad!—you cross the threshold into another world.

Goliath dunes stretch to the sky, unencumbered by grass or tree. Haughty moguls rise in a dizzying carousel of crests and curls, etched in a thousand strokes of gold: slices of melon, wedges of lemon, swirls of honey, streaks of cinnamon, and crowns of bronze. You have entered Oregon’s Planet Arrakis, Herbert’s empire of sand.

Imperious titans

Sand doesn’t come from the ocean—not this sand, anyway. The gritty particles that make up the Oregon Dunes originated from sedimentary rock high in the Coast Range, according to a 2007 research article by a distinguished panel of geologists. Rivers like the Umpqua and the Siuslaw tumble these relatively soft rocks relentlessly downstream, grinding them ever finer. Over millions of years, the rivers have carved epic canyons out of the mountains and dumped uncountable millions of tons of sand into the Pacific.

A complex interplay of current and wave washes the sand ashore. Then the wind takes over. In a process known as aeolian motion, wind heaps the sand into ridges. Along the water’s edge run the foredunes, smaller dunes that formed about 7,000 years ago. Behind them runs an imposing wall of older, grander dunes. And behind them, up to 3 miles from the shore, run the oldest, most majestic dunes, some built 100,000 years ago.

Up close, the face of the sand is tattooed with intricate ripples. Some parts are firm as concrete; in others, feet sink ankle-deep. The wind blows stronger the higher you climb, howling in ears, stinging eyes. The spiny ridges of the dune glow with a furious haze as the tempest drives the sand over the edge.

At the summit, behind a scalloped ledge on the slip face, the wind can’t find you. The gale drops to a whisper and you gaze spellbound upon this panorama of grit.

Amber waves of sand roll toward the horizon. The ocean is a vague memory, an insignificant strip of gray on the periphery. This is the domain of the wind. Up here, you can see how it has driven the sand into fantastic shapes and impossible geometries. Up here, the flow of time has slowed to a trickle, just as it did for Frank Herbert. Far below, a hawk hovers motionless, its wings tilted like a lazy seesaw. A creek winks from a distant stand of pines. You are one with the mountain

The sands of time

Herbert was haunted by the specter of unstoppable dunes. In Dune, he imagined a desert that swallowed an entire planet—an eerily prescient vision. The Gobi Desert creeps southward every year. Lake Chad has shrunk to a fraction of its former size. The Aral Sea has become a dust bowl.

In the Oregon Dunes, however, the problem is reversed.

The beach grass planted last century succeeded in halting the sand’s northward march. But that victory has come at a terrible price. Where the grass takes hold, roots burrow deep into the dune and weave themselves into a thick mat that traps sand and prevents it from blowing away. This allows shrubs like knotweed and Scotch broom to move in, followed by pine and spruce. These plants have smothered vast tracts of the dunes, reducing them to mere hills. The empire of sand is crumbling.

Groups such as the Oregon Dunes Restoration Collaborative now work to remove beach grass and invasive species and safeguard this unique landscape for future generations. Herbert would doubtless approve. Some of the most lyrical passages in Dune are, in fact, descriptions of dunes.

Sliding back down to the timberline, you’ll soon be hiking through a dense, shady stand of trees with branches festooned with Spanish moss. The forest floor feels reassuringly solid. But is it? Just a few feet below lies an ocean of sand, awaiting the turn of the tide.

Dune Voyages

John Dellenback Dunes Trail

If you want to hike big dunes up close, the Dellenback Trail is an excellent bet. A 15-minute walk through the forest leads to a stunning vista of gargantuan mounds of sand. Expect wind. You can hike to the ocean from here, but it’s a lot farther than you think. Hiking through sand is exhausting. We recommend coming here for the dunes and making a separate trip for the beach. The Eel Creek Campground is a convenient base of operations.

Oregon Dunes Loop Trail

This 4-mile hike offers an exhilarating tour of dunes and a spectacular walk on the beach. Wend your way through the dunes and stroll along the endless shore. The hike back is more challenging. Keep to the path. Long stretches of the foredunes are off-limits to protect the nesting habitat of the snowy plover, an endangered bird whose entire life cycle is spent along the shore.

Umpqua Lighthouse

Great spot to get your bearings. From here, you can see the dunes (but not access them). Follow the road down to find camping sites and ATV rentals. This is also a decent spot for whale watching—telescopes thoughtfully provided.

Siuslaw Public Library

Located in scenic downtown Florence, this library boasts a unique collection of Dune arcana, thanks to Frank Herbert’s daughter, Penny Herbert Merritt. A longtime resident of Florence, she donated her father’s personal collection of books to the library shortly after it opened in 1990. Today, the catalog of Frank Herbert items is 14 pages long and includes such gems as a Korean version of Dune and books on botany, Tolstoy, and Stalingrad.

Touring the Dunes

If you don’t want to hike, Ocean Breeze (florenceoregonatvrentals.com) and Sandland Adventures (sandland.com) in Florence rent dune buggies. (Sandland also offers guided tours.) For a quieter option, C&M Stables (oregonhorsebackriding.com) has led horseback rides through the coastal forests and dunes just north of Florence since 1981. You can also paddle along the dunes. Rent a kayak, canoe or other watercraft from Oregon Paddle Sports (oregonpaddlesports.com/rentals/rental-boats).

Learn more

Save the Oregon Dunes (saveoregondunes.org) organizes regular beach restoration events to protect this natural wonder. It can always use help.

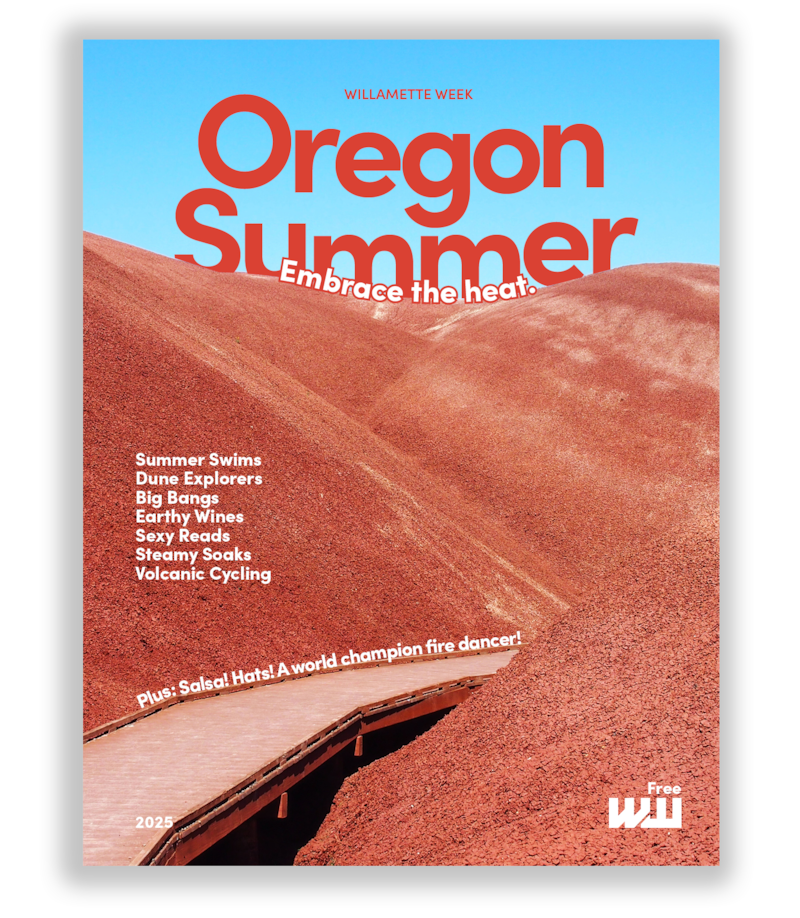

This story is part of Oregon Summer Magazine, Willamette Week’s annual guide to the summer months, this year focused on making the most of and beating the heat. It is free and can be found all over Portland beginning Sunday, June 29, 2025. Find a copy at one of the locations noted on this map before they all get picked up! Read more from Oregon Summer magazine online here.

Opens in new window

Opens in new window