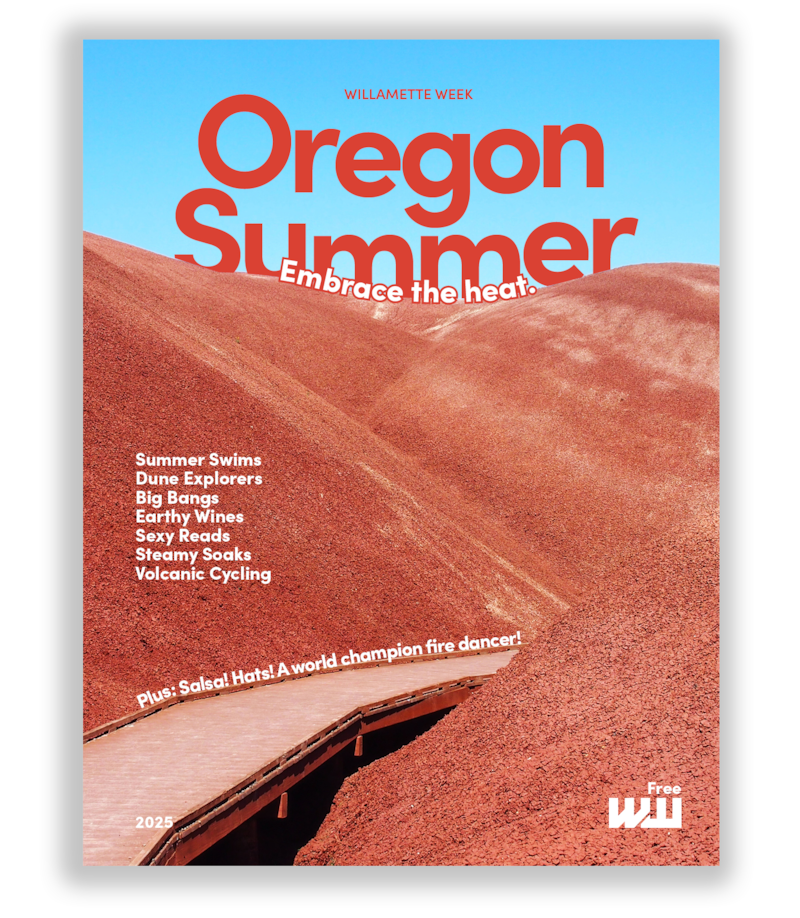

The Pacific Northwest: The name implies that the ocean defines this region. And we’re not here to argue that a gazillion tons of seawater is irrelevant. But—no disrespect to Poseidon—when it comes to appreciating the elemental forces sculpting our geography, forget the ocean. All hail Vulcan; seek the fire.

To understand the rocks and the rivers, the forests and the deserts and the rain, look to those gargantuan peaks that dominate the skyline. They’re not mere mountains, they’re volcanoes, where fiery forces seethe deep beneath the surface.

Over the course of millions of years, they have unleashed gushing rivers of heat that have shaped our landscape and our destiny.

“Basically all of Oregon is volcanic in one form or another,” says Oregon State University volcanologist Bill Chadwick.

This is a summer guide, so we won’t get too wonky, but a little science helps to explain these explosive marvels. The earth’s crust is anywhere from 3 to 44 miles thick. That sounds like a lot, but when you compare it to the diameter of the planet, it’s roughly proportional to an eggshell. Sometimes the crust fractures and the boundary between the overworld and the underworld grows thin. Magma from the mantle finds its way to the surface, where it erupts as lava or ash and gas—sometimes in spectacular spurts, sometimes like a rusty dribble from a backyard hose. Either way, these torrents of molten rock or pulverized dirt make mountains and push islands up out of the sea.

The Cascade Range is home to several active volcanoes—Rainier, St. Helens, and Hood all recorded earthquakes last month alone—and scores of dormant ones. Battle Ground Lake is actually a submerged volcano whose crater is now full of water and lovely for a summer swim. Portland sits atop a geological formation known as the Boring Lava Field (see “Cruising Portland’s Lava Flows,” page 72).

If you want to get a handle on the significance of this intense heat, take a trip to a volcano. From a distance, they look serene and proud. Up close, you can find the clues to their immense power—the power to destroy everything that stands in their way, but also the power to create new rivers and lakes, and sustain new forms of life.

Axial Seamount

The beast awakens

Axial Seamount is waking up.

It could blow at any moment. Seriously. It may have already happened by the time you read this. It might be happening today.

Axial is the most active volcano in the Pacific Northwest, but you’ve probably never heard of it because it’s underwater. Located roughly 300 miles west of Newport, Axial sits at the junction of two tectonic plates, the Juan de Fuca and Pacific plates. Continental drift is slowly tugging these two plates apart like slices of pizza oozing with cheese. The result? A long, fiery chain of volcanoes, also known as seamounts, running along the axis between them.

Axial is the mightiest of these submerged giants, standing about 3,600 feet above the seafloor, and the most temperamental. It erupted in 1998, 2011, and 2015—and scientists are predicting another explosion any day now.

Unless you own a submersible, the best way to experience Axial is by visiting Oregon State University’s Hatfield Marine Science Center (2030 SE Marine Science Drive, Newport, hmsc.oregonstate.edu), which features several interactive exhibits about the volcano and the sophisticated equipment researchers use to monitor it. Situated in the shadow of the better-known Oregon Coast Aquarium (2820 SE Ferry Slip Road, Newport, tickets.aquarium.org), the Science Center explores humanity’s symbiotic relationship with the earth.

One of its researchers is the volcanologist Bill Chadwick, who has been tracking Axial for more than 20 years. Working together with scientists from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Chadwick and the team at OSU correctly predicted the 2011 eruption and the 2015 eruption that flooded the seafloor with a layer of lava taller than PacWest Center. Thanks to an advanced system of sensors that researchers installed on the ocean floor, he can check the volcano’s heartbeat on his cellphone.

Chadwick is betting the next eruption will take place sometime this year. The telltale signs are mounting. Axial has been slowly puffing out its chest (“inflation” is the technical term) at the rate of 22 centimeters a year. It’s now at or above the levels that triggered the eruptions of 2011 and 2015. It’s registering more pressure and more earthquakes—about a hundred a day. “We think we’re in the final stages of the buildup,” he says, hopefully. “Every day, I look at the pressure data and wonder if today’s gonna be the day.”

Submarine volcanoes (no, that’s not a band name) are far more numerous than their earthbound counterparts, which makes sense when you consider that roughly two-thirds of the planet’s surface is covered in water. Many of them, including Axial, generate hydrothermal vents, which are long cracks or fissures where seawater gets superheated to temperatures of 500 degrees. (The water can get hotter than its normal boiling point because of the enormous pressure at this depth.) This water dissolves elements from the volcanic rock, forming thick plumes known as “black smokers.”

Dwelling in perpetual gloom, these black smokers support colonies of incredible microorganisms by chemosynthesis rather than photosynthesis. These colonies nourish bizarre life forms such as tube worms, sea spiders, blind crabs, and inkless octopuses.

Visiting the Science Center and the Oregon Coast Aquarium are only two of many reasons to visit the central Oregon Coast (see “Let It Melt,” page 59). Watching the Axial blow won’t be one of them. The volcano lies almost a mile beneath the ocean’s surface, far too deep to trigger a tsunami. The lava will emit a cheery red glow, but a billion tons of seawater will soon cool its jets. Each new eruption spreads a fresh layer of lava; Axial is getting taller and taller. The volcano lies so deep that geologists can’t be certain how long it might take to reach the surface and give birth to a new island. It may take millions of years, but it’s coming.

Mount St. Helens

The Big Bang

Most Portlanders know some basic facts about Mount St. Helens. It blew its top on May 18, 1980. The eruption knocked down a lot of trees. It dumped a thick coat of ash across a giant swathe of Washington and Idaho. Portland schools were closed for “ash days.”

But there’s a lot you may have forgotten or never known about this cataclysmic event.

For one, it didn’t blow its top. The force of the eruption blasted apart the side of the mountain, which is partly why it was the most destructive eruption in the recorded history of the United States. Rather than going up, where some of the force could dissipate before hitting land, the explosion directed the fury of a 24-megaton bomb down the north side of the mountain, covering an area the size of Chicago. It unleashed titanic lahars (tidal waves of mud) that drowned the Toutle River and gunked up the Columbia for miles. It killed 57 people.

Reaching back into the quaint times before the internet, I have childhood memories of a colorful old codger named Harry R. Truman who became a local celebrity for refusing to abandon his Mount St. Helens cabin. Schoolkids wrote him letters begging him to leave, but he died in the blast. More recently, I’ve been surprised to learn that he was one of only five people who lost their lives inside the so-called red zone. Nearly everyone else who died—parents, children, honeymooners, loggers, photographers—were in places they had been told were out of harm’s way. A good reminder that we still have a long way to go in our understanding of the earth’s rumblings.

Also, St. Helens (Lawetlat’la in the Cowlitz language, and Loowit in Klickitat) isn’t named for a saint. British explorer Captain George Vancouver gave it this moniker in 1792 to honor a buddy of his, a certain Alleyne Fitzherbert, the 1st Baron St. Helens, who ruled over a village on the Isle of Wight.

Today, you can approach Mount St. Helens from three directions: east, south, and northwest. If you choose northwest, the Mount St. Helens Visitor Center (3029 Spirit Lake Highway, parks.wa.gov/mount-st-helens-visitor-center) just up the hill from Castle Rock, is an excellent place to start your adventure. Fresh from a brand-new remodel reopened May 31, the center offers interactive, accessible exhibits such as a quake lab, a functioning seismograph, a walk-through volcano model, a volcano blasters pinball machine, a 3D relief map, and 80 historic artifacts, many belonging to the Cowlitz people. Park ranger Alysa Adams says the exhibits are designed to appeal to three types of visitors: “streakers (with clothes on), strollers, and studiers.” The museum also includes places for reflection since it interprets death, loss, and destruction.

Adams hopes the new center encourages visitors to “pause and watch nature do its thing” and come away with the understanding that “volcanoes are capable of creating new life.”

As the crow flies, the visitor center is 30 miles from the crater, but the mudflow from the 1980 eruption was so gigantic that it swallowed everything in its path, including the spot where the visitor center now stands.

Something to think about when you camp at nearby Seaquest State Park, one of many stops you can make heading up Highway 504, otherwise known as Spirit Lake Highway.

You’ll pass the Cascades Sasquatch Research Organization, which features an immense Bigfoot statue, the skeleton of an A-frame house buried by ash flows, a rustic campground, and a gift shop. There’s also a poignant display of several destroyed vehicles, with descriptions of the people who died in them.

The temperature drops and the excitement builds as you wind your way farther up the highway, which was built above the North Fork of the Toutle River to replace the old road that was demolished in 1980.

The Forest Learning Center (a free summer-only museum operated by Weyerhaeuser) and the Castle Lake Viewpoint offer spectacular views. Inside the Learning Center, located just within the volcanic blast zone, you learn about the remarkably fast recovery of forests, fish, and wildlife following the eruption. Outside, you can see the volcano’s monumental crescent, clenched like a giant hand around the remains of the crater. Far below, the Toutle River meanders through a valley that was blasted into moonscape by the eruption but has since made a comeback.

Since 2023, you can no longer drive to the Johnston Ridge Observatory (it’s situated near the site of volcanologist David A. Johnston’s camp where he was killed on the morning of the blast). A mudslide washed out the road and plans are still being developed to rebuild it; 2027 is the optimistic estimate.

The Science and Learning Center, located 7 miles from the crater at milepost 43, offers amazing views, hands-on exhibits and a vast array of interactive and educational programs, including the chance to stay overnight in the center. Coldwater Lake is a great place for a hike or a paddle or to cake. The lake was formed by a mudslide from the 1980 eruption that stoppered up the North Fork of the Toutle River, forming a ribbon of lake 5 miles long. Geologists warned that this barrier was unstable, however, raising the possibility of a catastrophic failure and creating an existential dilemma about whether to intervene. (Dammed if you do, damned if you don’t.) In the end, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers constructed a spillway to give the water an easy out.

There are many opportunities for hiking and climbing. The 2.5-mile Hummocks Trail leads past Hobbit-green mounds.

Up close, St. Helens resembles a savage sphinx, its jagged claws curled around the lava dome. It is humbling to realize that the mountain has thrown several tantrums that were even more destructive than the 1980 blast, and still experiences frequent earthquakes and landslides. In fact, St. Helens is the Cascades volcano that scientists reckon is the most likely to erupt in our lifetime.

You can also enter the St. Helens zone from the south. Taking Highway 503 from Woodland leads explorers to the popular Ape Cave, a fantastic place for novice spelunkers to escape the summer heat. It’s the third-longest lava tube in North America at 2.5 miles long. Make a reservation at recreation.gov. Nearby June Lake is a popular day hike of less than 3 miles round trip.

The eastern side of the mountain has been the slowest to recover, with fields of blown-down trees, piles of ash, and arid landscapes. Forty-five years after the explosion, take the Norway Pass hike (4.5 miles round trip) to witness up close St. Helens’ might.

Mount Mazama

The wizard and the phantom

On your quest for the heat, you must sometimes endure the cold.

Once upon a time, Mount Mazama stood tall and proud, the undisputed ruler of its icy domain. But roughly 7,700 years ago, the volcano erupted with cataclysmic force, hurling lava and ash into the air in a great plume that darkened the sky and drifted as far as Greenland. The explosion was so titanic that the entire mountain collapsed into the magma chamber beneath it, leaving behind a monumental hole now known as Crater Lake.

Approaching from Highway 62, Crater Lake Highway, take the scenic Munson Valley Road that winds its way up the flank of the giant. Finally, about 7,000 feet above sea level, find your way to Rim Village, park the van, and get ready for the thrill of a lifetime: the incandescent blue immensity of one of the deepest lakes in the world.

There are many ways to explore this ghostly goliath. You can circumnavigate it on Rim Drive, which runs 33 miles and features 30 overlooks. In theory you can drive this in two hours, but give yourself more time than that—this is something you don’t want to hurry!

Crater Lake also offers glorious hiking. Starting from Rim Village on the south side, you can basically hike clockwise around the rim 6 miles to North Junction.

If you’re short on time (or just feeling lazy) try the Sun Notch Trail. Barely a mile out and back, it offers a spectacular view of the Phantom Ship.

For the more adventurous, consider hiking the Cleetwood Cove Trail from the north side of the rim down to the shore of the lake. Described as “steep and strenuous” on the National Park Service website, this is the only way to access the lake. The trail is 2.1 miles down and back up, with an elevation change of 700 feet, equivalent to climbing 65 flights of stairs. (Remember you’re at a high elevation and give yourself plenty of extra time for this.)

The trail leads to a small dock. From here, you can book a boat to one of the lake’s most bewitching attractions: Wizard Island, the remnants of the volcano’s cinder cone. Or seize the day and go for a dip. In the summertime, the surface temperature of the lake hovers around 57 degrees, about the same as the Oregon Coast. To preserve the clarity of the lake and prevent invasive species, you can’t bring wet suits, boats, kayaks, rafts, or any other playthings. The water may be chilly, but that long hike back will warm you right up.

Starting in 2026, the park service plans to close the Cleetwood trail for repairs. It won’t reopen till 2029, so go this year if you can.

No matter how you plan to enjoy Crater Lake, bring a jacket. The temperature on the rim swings wildly, especially in summer months, when days can top 90 degrees but nights plunge to freezing. You’ll experience the marvel of fire and ice.

To gain a deeper and more intimate understanding of the enduring fascination with volcanoes, check out the 2022 documentary Fire of Love. Narrated by Miranda July, of all people, the film pieces together decades of footage to reveal the passions of scientists Katia and Maurice Krafft, who came together to discover and show the world the mysteries of volcanoes and tragically died in the effort.

This story is part of Oregon Summer Magazine, Willamette Week’s annual guide to the summer months, this year focused on making the most of and beating the heat. It is free and can be found all over Portland beginning Sunday, June 29, 2025. Find a copy at one of the locations noted on this map before they all get picked up! Read more from Oregon Summer magazine online here.

Opens in new window

Opens in new window