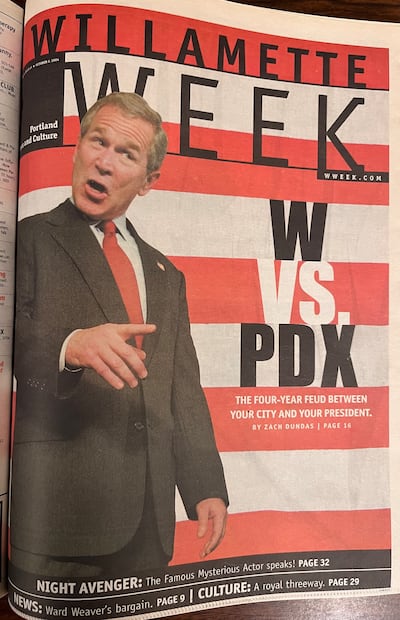

This story first appeared in the Oct. 6, 2004 edition of WW.

Let’s face it. This was never going to work.

Portland voted for Al Gore by a margin Vladimir Putin would envy. It was never going to warm to the man who beat him. (Or whatever.) This is, after all, the city George W. Bush’s dad branded “Little Beirut.”

But sweet Mary—who knew it would be this bad?

Today, to drive, walk, drink or dine in Portland is to learn just how badly most of the Rose City wants John Kerry to become Leader of the Free World. Stickers. Graffiti. Invective. The sharpest political division in Portland separates those who think W is a lousy president from those who believe aliens sent him to destroy Earth.

Yeah, it’s mostly about Iraq. And about Osama, North Korea, Iran, Muqtada and Karl Rove.

But what even the most vigilant Bush-loathers often overlook is how federal policy decisions on more mundane matters come home to roost. So this week, we look beyond Iraq—though we get there, too—to examine ways this administration has affected our fair metropolis.

Yes, this city may love to hate W. But look at what’s happened on his watch, and you get the idea the feeling’s mutual.

Put down the Visa card, Mr. President. Back away slowly.

“The budget deficit! Goddamn it, it’s the most important story there is!”

It’s not often that economists launch into breathless tirades. But that’s what happened when WW asked Portland econ Joe Cortright about the Bush administration’s effect on Portland pocketbooks.

Cortright says almost nobody’s paying attention to the massive swing—from a $236 billion budget surplus four years ago to the $444 billion deficit—on Bush’ s watch. In practical terms, that swing has put an invisible monkey on our backs. The federal gub’mint ran up $1,289 in debt for every person in the city in 2003. In 2004, W’s killer combo of falling revenues (thanks to a lousy economy and massive tax cuts) and rising costs (Iraq) will put $1,513 on each Portlander’s unseen Visa bill.

And Cortright says the most insidious effect is that the pain won’t come until long after November.

“It’s as if somebody gave you $500 in cash today, ” Cortright says of Bush’s tax rollback, “and then ran up thousands in debt on your credit card, and then arranged so you won’t get a bill until after the election.”

When there’s a deficit, the government borrows money to pay for it. That money must be paid back someday—unless we plan to pull an Argentina by defaulting and ruining our national credit forever. The local implications? Cortright says—and other economists agree—that as the bills pile up, services vanish.

So when we talk about Head Start, transportation, crime-fighting and the unfunded gorilla that is No Child Left Behind, remember the deficit.

“What Bush has done,” Cortright says, “is essentially mortgaged our future.”

Li’s Lost Year

Li, a 22-year-old biochem major from Suzhou, China, has just a year to go before she can wrap her hands around a sheepskin diploma from Portland State University.

First, though, she has to convince the State Department to let her finish school.

In her first three years at PSU, Li (who asked WW not to use her full name) went home to northeast China to visit her family several times. She had no idea, when she flew back for summer vacation, that she wouldn’t be allowed back in the United States.

The Justice Department deems Li’s plan to take a full load of upper-division biochemistry classes suspicious. Even after she completed a mandatory interview imposed on most foreign college students after 9/11—and even though she comes from China, not, say, Saudi Arabia—the feds won’t sign off on her student visa.

Both Li and PSU are mystified. She has to do another interview in China in early November. If it goes well, she might be back at PSU in three to six months. If not, she figures it will take a year.

“I was planning to go to graduate school after summer graduation,” Li wrote in an email. “Now, it seems impossible because I’ll miss the application period this fall.”

The would-be scientist is far from the only Portland State student grappling with daunting new federal restrictions on foreign scholars.

No one disputes the need to keep the United States safe from marauding terrorists who could pose as science geeks. (The Justice Department gives special scrutiny to science majors , as well as students from 19 “high risk” countries.) But Portland State is watching its international population dwindle. The school won’t have final enrollment numbers until the end of October, but it estimates last year’s foreign-student body of 1,218 will drop by at least 7 percent, and as much as 17 percent.

“The world did change after 9/11,” acknowledges Gil Latz, PSU’ s interim vice provost for international affairs. “But restricting access to the Oregon education system is unfortunate and counterproductive. The U.S. has been the great beacon for foreign students for 50 years, but that’s changing, all in the name of security.”

The decline hurts Oregon’s largest university in ways that have nothing to do with “multiculturalism.” Foreign kids, bluntly, are a huge cash cow. International students shell out between $12,250 and $13,250 per year to the school, three times what the average homegrown student pays. Boosting foreign enrollment is the centerpiece of Portland State’s drive to build more housing around campus.

That, in turn, is a key to the city of Portland’s hopes for the downtown district around the campus—an area as big as the Pearl District at the heart of the city.

Li had no idea she was so important (or “suspicious”). She just wants to get back to school.

Does W Stand for Road Warrior?

Every six years, Congress passes a huge bill to pay for transportation projects—highways , bridges, railroads, local road improvements , bus routes, even bike paths.

This time, the bill is stalled. Bush says he’ll veto anything that spends more than $256 billion—but that’s much less than either house of Congress, Republicans and Democrats, wants to spend. Bush has never vetoed a bill, and Republicans don’t want to see Congress override him before the election. So they’re just not passing it.

“This is all about Bush pretending to be a fiscal conservative,” says Portland U.S. Rep. Earl Blumenauer, a Democrat. “Any bill we’d pass would have a veto-proof majority. So we have no bill.”

The stall is holding up projects all around Portland. Freight haulers and commuters desperately need a new bridge to Vancouver, Wash., but the $11 million needed to start that project is stuck. So is $4.8 million for wider sidewalks and better traffic signals in Gateway, as well as $3 million for the eastside streetcar extension.

Gresham wants to give a $2 million facelift to its troubled Rockwood Town Center, but can’t. The Port of Portland can’t get $12 million it needs to improve rail traffic at North Portland’s Rivergate Industrial District. For that matter, a paltry $200,000 needed to improve Burlington Northern’s hub in Northwest Portland is also hung up.

All these delays mean something else: less work.

“In transportation, spending $1 billion generates 40,000 to 60,000 jobs,” Blurnenauer says. “Oregon would probably get $1 or $2 billion if we could pass a bill. We could put people to work in a matter of weeks on all kinds of projects.”

No One to Watch Over You

W and the Republican Congress want to keep you safe, right? Why, then, is the office that keeps watch over 1,000 crooks in Portland short of cash? Portland’s federal probation office watches over criminals released by federal pens or placed on probation by federal judges. In the past year, thanks to cuts to the federal judiciary’s overall budget, the office has lost about six full-time positions from a staff of about 40.

Local law-enforcement officials say that means criminals under federal supervision will probably commit more crimes.

“It means potentially more people in our jails,” explains Multnomah County Sheriff Bernie Giusto. Multnomah County’s jails, first stop for any federal parolee who breaks the law in Portland, are so full they often release thieves, burglars and drug criminals early.

“They won’t be slipping through the cracks,” says Giusto of reduced oversight of Portland’s federal criminals, ‘’but off a cliff."

Smarter Cops? Who Needs ‘Em?

You’d think an administration obsessed with security would love a program that churns out new, improved cops.

But Police Corps, a federally funded program that recruits better-educated cops and gives them

expanded training before they join local agencies, is taking a $15 million hit nationally from W’s budget-cutters. The 50 percent reduction means Oregon’s Corps branch, which started in 1996, is shrinking fast.

“We used to be able to fill as many slots as we could find recruits for,” says Capt. Donna Henderson, the Portland cop who oversees Oregon’s program. “Last year, it was 20. This year, we have 11.”

The program lures recruits with college scholarships of $3,750 per year if they agree to serve four years in law enforcement after school. In Oregon, Police Corps recruits then spend 1,300 hours training at a Salvation Army camp in Clackamas County-roughly three times more preparation than an average cop gets.

And local cops say it’s not just a boot camp.

“Oregon’s program is innovative in ways other states’ aren’t,” says Cmdr. Rosie Sizer, who runs the Portland Police Bureau’s Central Precinct. “The program emphasizes ethics, multiculturalism and dealing with the disadvantaged. The people they’ve brought in are good.”

The numbers show the bureau at large backs Sizer’s assessment. Of Oregon Police Corps’ 160 total grads, Portland snapped up 96. “We talk to sergeants, street officers and chiefs all over the state,” Henderson says. “Without exception, they say they want as many Police Corps grads as they can get. The cuts reduce how many of those officers we can put on the streets.”

Roadless Schmoadless

In the last days of the Clinton administration, a new rule preserving almost 60 million acres of

pristine National Forest land across the country took effect. The Roadless Rule came after 1.6 million public comments, the most in the history of federal rule-making.

Team W is gutting the rule, which protects stands of 5,000 or more roadless acres. First, earlier this year, Agriculture Undersecretary Mark Rey—a former timber-industry lobbyist exempted Alaska, home to the two largest national forests. Now , the administration wants to scrap the Clinton rule entirely.

“It had the support of environmentalists, hunters, anglers, Easterners, Westerners, Republicans and Democrats,” says Ken Rait, the Portlander who ran the national campaign that pushed for the rule. “It was probably the biggest single conservation move by any president since Teddy Roosevelt.”

Bush wants a system in which each state’s governor would have to apply to preserve roadless areas. That would strip protection from places like Roaring River, an expanse of 27,000 acres 19 miles southeast of Estacada, an hour from Portland. Other gems in the Mount Hood National Forest, like Twin Lakes and Mirror Lake, could also be opened to roads, logging and other development.

Rait and other environmentalists say that for many Western governors, requesting roadless protection would be political suicide. In any case, the Bush administration could refuse to protect land even if governors wanted it to.

Right now, the new, W-approved rule change is still in the works. The public comment period was recently extended—the original September deadline was postponed, coincidentally or not, to mid-November.

“They won’t finalize this until after the election,” Rait says. ‘They don’t want to show their true colors while they’re trying to mine votes in places like Washington County, where people understand the value of wild land."

Heading off Head Start

Mount Hood Community College’s Head Start program serves poor kids under the age of 5. They come from all over the outer east side—from Parkrose, Clackamas and Gresham. A family of four must have an income below $18,850 for their kids to qualify.

Right now, there are more than 700 kids in Mount Hood’s federally funded classes—and that’s great. The problem is, Mount Hood turns away about 800 eligible kids every year. Now, thanks to Bushie budget cuts, the program will have to boot 20 more kids next year.

W’s proposed budget for ’06 contains a $177 million chop to the national Head Start program. Portland programs like Mount Hood and the well-known Albina Head Start will cut staff and lose slots for kids. Albina cut three staff positions and said buh-bye to 20 kids after losing $250,000 in state funding last year. Director Ron Herndon, who has worked in Head Start since 1975, says he fears federal cuts will mean more of the same.

“I have never seen an administration that has wanted to, and has done, as much harm to Head Start as this administration,” Herndon says.

Why Boilermakers Are Drinking More Boilermakers

Five years ago, according to Business Manager Rick Lazott, Portland’s branch of the International Brotherhood of Boilermakers had about 500 members. They worked good jobs—on average, Lazott says, boilermakers make $19 an hour fixing broken-down ships at the Port of Portland.

Lazott says Local 72 now has about 250 members. He blames the decline on a largely obscure provision of an equally obscure treaty W signed in 2002, setting up free trade with the Asian city-state of Singapore.

The treaty exempted Singapore from an antique U.S. law that required U.S.-flagged ships to be repaired in American ports or pay a penalty. The U.S. doesn’t have a big merchant navy anymore. But there are vessels—like Alaska oil tankers—required to fly the Stars and Stripes. Lazott says the repair requirement ensured that places like Portland got work from such ships.

“It’s killing us,” he says. “It’s hurting the pipefitters, the sheet-metal guys, the machinists, everyone.” Singapore’s growing, aggressive, dirt-cheap dry docks have a huge advantage in luring ships.

Look: Without international trade, America would grind to a halt, starting at Target. The left needs a whole new approach to the issue. But it seems to us that there’s a time to apply some common sense, and the brakes. Like when unemployment in a port-dependent West Coast state is in six figures (more than 130,000 Oregonians were looking for work in August).

But W, who loves free trade as long as Halliburton isn’t involved, barreled forward with the Singapore deal.

“Bush has a much more aggressive approach to free trade than Clinton,” says Tim Nesbitt of the Oregon AFL-CIO. “lt’s beyond what fast-track means.”

Bye, Teacher! (Bus Fare, Please?)

W’s national education policy, No Child Left Behind, contains a provision that allows students to transfer to new schools when their old ones don’t meet federal standards.

A lot of people think that’s a good thing. But like much of No Child Left Behind—which imposes

new testing regimes and requires new instructional materials-this is a classic unfunded mandate.

This year, Oregon’s biggest public district will foot the bill for kids who want to skedaddle from nine Portland schools, including four of the seven eastside high schools.

Portland plans to cover that half-million-dollar cost out of the $14.8 million the district will receive in Title I funds this year. Problem is, Title I funds—federal dollars meant to help low-income students—are stretched thin.

“It’s an inefficient reallocation of resources,” says Jan Chambers of the Oregon Education Association. “We should be putting that money into what we know works: smaller class sizes, teacher training, up-to-date textbooks.”

Bum-Rushing the Guard

We could argue all day about whether W’s invasion of Iraq was right or wrong. Let’s not. Let’s just agree that the execution of this war of choice has been beyond bad.

To us, the most compelling proof that W went to Baghdad without a clue comes not from bloodbaths in Fallujah and Najaf, nor the rise of Muqtada al-Sadr. It lies in the evidence that he sent hundreds of Oregon National Guardsmen—including a Portland company—to fight without the proper equipment or training.

Oregon congressional offices say many reservists arrived in Iraq without body armor, boots or other gear. Left-handed soldiers weren’t issued the right kind of rifles. Patiol Humvees lacked armor to ward off the roadside bombs favored by militants. According to an Oregon Guard official, soldiers dubbed the vehicles “cardboard coffins.”

Families chipped in and congressmen screamed-and the equipment problems, similar to those faced by troops all over Iraq, have reportedly eased. The violence has not.

The Oregon Guard is in a rough spot, patrolling Baghdad and areas north. Nine Guardsmen have been killed. In the last weeks of September, Portlanders David Weisenberg and David Johnson died when bombs hit their Hurnvees.

The very fact they died on wheels, some say, highlights the defects in the Bush administration’s rush into Iraq.

The main Oregon outfit in Iraq is an infantry battalion, trained to fight on foot. But it’s been converted into a unit that fights in Humvees—a major shift in duty, one official says, for which the reservists trained only briefly in Texas before deploying to Iraq.

“It goes to the root of the problem,” says Col. Mike Caldwell of the state’s Military Department, which oversees Oregon Guard units in peacetime, “which is that there was no plan to get this job done. A lot of soldiers just get a quick spin-up on whatever they’re going to do, take whatever equipment is available at the time, and go.

“It’s like we went to war and forgot the bullets. It’s about that dumb.”