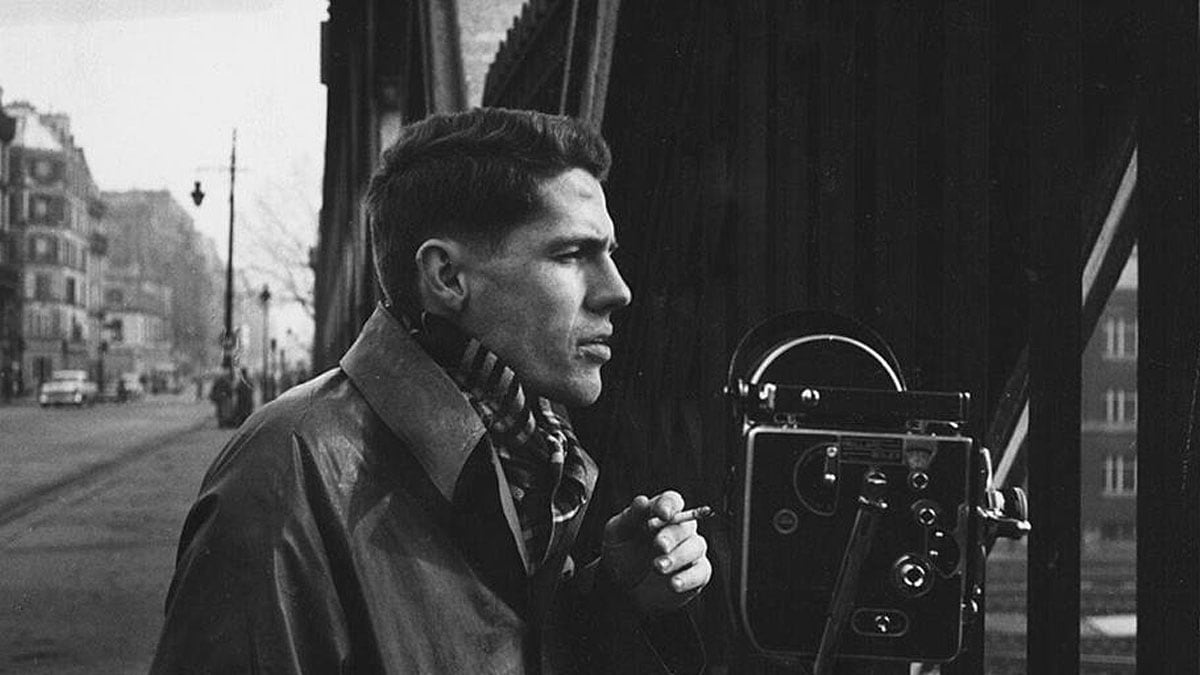

In 1962, Portland-raised and University of Oregon-educated James Blue became the first American filmmaker to win the Critics Prize at Cannes. About the fall of French colonialism in Algeria, Les Oliviers de la Justice was praised for its realism and the unusual choice of hiring local non-actors for prominent roles. Unlike most of his later works, Les Oliviers is fiction. But the film hinted at Blue's ideal of "democratized media"—films that were less concerned with the filmmaker's perspective than with voices of the voiceless and of the audience themselves.

But outside of academic circles, Blue's name and legacy aren't exactly well known. Daniel Miller is trying to change that. His new film Citizen Blue: The Life and Art of Cinema Master James Blue, seeks to illuminate the life and career of an underappreciated innovator of cinema. "I think certainly that James Blue's goals, as I have discovered them, were always about learning who we are as human beings changing and affecting the world for better or worse," says Miller.

Miller is a filmmaker and professor at University of Oregon, which houses the James Blue archives in its Special Collections. He's also the director of the Oregon Documentary Project, a program that helps student filmmakers create documentaries about issues relevant to the Pacific Northwest. In his time with ODP, Miller has advised students in the production of more than 75 short documentary films.

Miller's work with OPD is very much in line with the legacy he hopes to honor in Citizen Blue. Through archival footage and interviews, Citizen Blue tells the story of an artist and scholar who helped make independent filmmaking what it is today and who's ideas of how to communicate social issues through media were far ahead of his time.

Following his success at Cannes with Les Oliviers, Blue began working for a vaguely-named governmental appendage called the United States Information Agency, whose main function was to produce informational films only meant to be screened outside the U.S. Even the works he made for the Cold War agency were idiosyncratic, open-ended films. However, it meant that many of his movies couldn't be viewed in the US until after the fall of the USSR.

During his time with the USIA, he directed the iconic documentary about the Civil Rights movement, The March, which was added to the National Film Registry in 2008. A few years later, he also made A Few Notes On Our Food Problem, which examined food production in impoverished parts of three continents and won an Academy Award nomination for Best Documentary in 1968.

Later in his career, Blue took his idea of democratizing the media a step farther. While teaching at Houston's Rice University in the late '70s, Blue made Who Killed The 4th Ward? and The Invisible City, both of which tackled issues of poverty and housing crises in Houston. The films were made in multiple installments, and invited viewers to call or write in between each part with suggestions about where they'd like to see the film go.

But according to Miller, Blue's commitment to varied representation by media extended beyond his films. Blue served on the National Endowment for the Humanities first Public Media Panel, which determined a model for federal art funding that paved the way for independent filmmaking. Blue was instrumental in the push to spend federal money on regional centers and individual filmmakers instead of just two national centers.

"He favored democratizing media, and the NEA took up this sympathy as policy," says Miller. "Thus began the possibility of independent films and important regional institutions such as Portland's Northwest Film Center and the Pacific Film Archive in Berkeley."

In 1980, Blue passed away from cancer at the age of 49. But his legacy is still very much alive. In some ways, we have achieved a democratized media with independent filmmaking resources like Miller's own work with the Oregon Documentary Project. But it's difficult to gage how close we've come or how far we've strayed from Blue's idealistic vision. What would James Blue think about the rise of YouTube and media agencies that bend the truth around the visions of their supporters?

Miller doesn't have the answers, but he believes Blue's career at least provides crucial context. "I believe his contribution will resonate and grow stronger the more people investigate his work," he says.

SEE IT: Citizen Blue: The Life and Art of Cinema Master James Blue is at NW Film Center's Whitsell Auditorium, 1219 SW Park Ave., nwfilm.org. 7 pm Thursday, Oct. 19. $9.