How do you dress a man with no name? That’s the question Ruth E. Carter faced nearly 20 years ago as she crafted a suitably lethal-looking outfit for the Operative (Chiwetel Ejiofor), the relentless lawman who pursues Capt. Malcolm Reynolds (Nathan Fillion) across the cosmos in Joss Whedon’s Serenity (2005).

“Chiwetel’s jacket I remembered being inspired by an avant-garde Japanese designer who had the stitching lines totally going against the body form,” Carter says. “I thought, how can I create something like that for [the character] that would say so much about what is unique to him?”

While Carter is best known as the first African American woman to win the Best Costume Design Oscar—for Black Panther (2018)—her triumphs are beyond trophies. Whether she’s working with Spike Lee or Steven Spielberg, she creates costumes that convey character through exquisite detail, like the height of a shirt’s collar or the width of a jacket’s shoulders.

On March 8, Carter will visit the Tomorrow Theater for a Q&A with PAM CUT director Amy Dotson (the theater will also present a free screening of Black Panther on March 7). Carter spoke to WW about her career and her new book, The Art of Ruth Carter: Costuming Black History and the Afrofuture, from Do the Right Thing to Black Panther.

WW: Your costumes reveal so much about character. In Serenity, for instance, you see Chiwetel Ejiofor’s body armor and you instantly know his character will get the job no matter what, with minimal fuss.

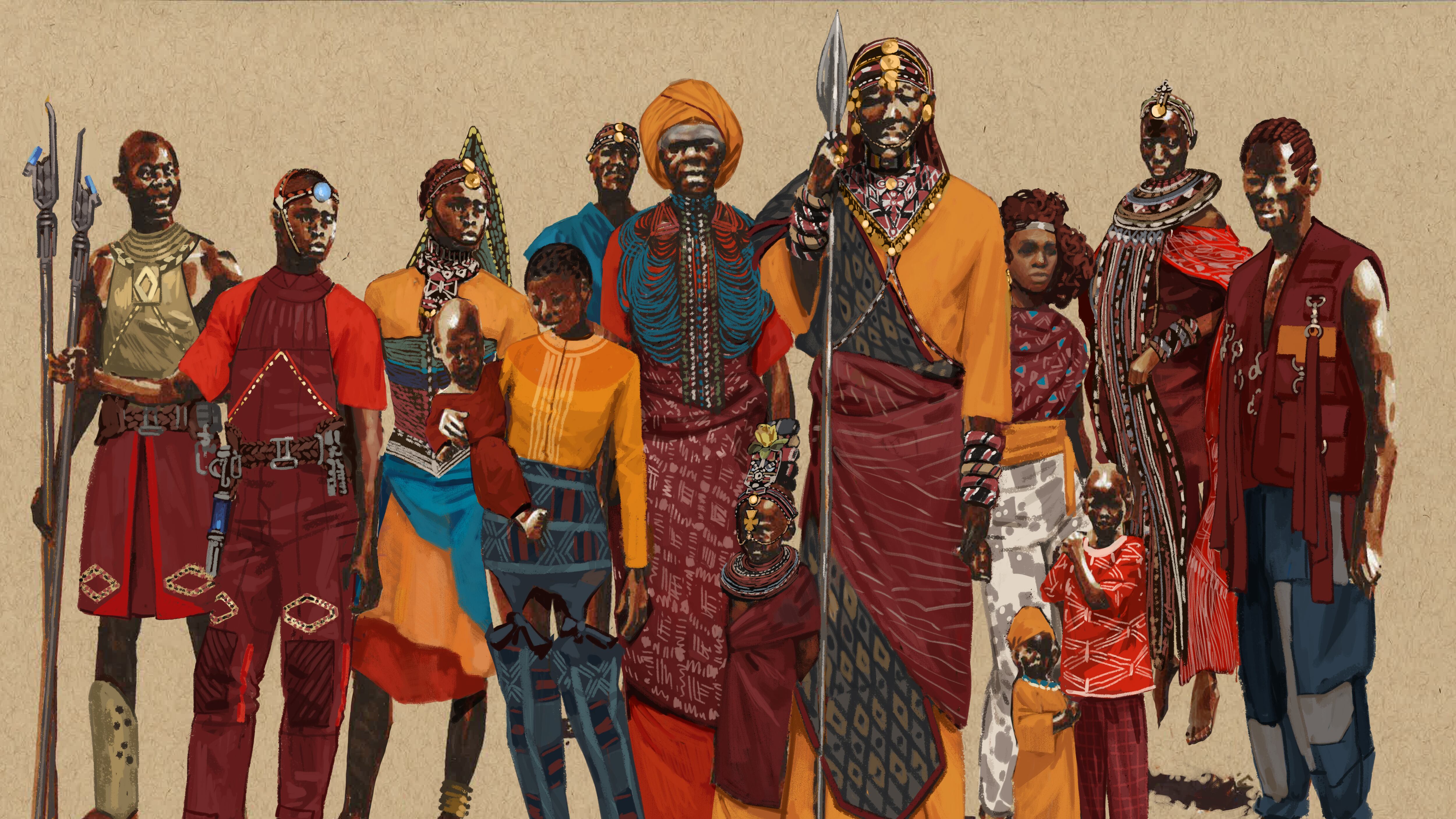

Ruth E. Carter: You tapped some of my early work in Afrofuture. Serenity was an Afro-Western—a future Western. It’s not like, oh, that was the ‘80s when they wore shoulder pads. I’m not trying to follow trends or fads that are dated. I want to really dive into storytelling so that the characters live forever in our minds.

How do you decide how closely to stick to the historical record when you’re doing a period piece?

You have to be perfectly imperfect: Today he has an apple in his pocket and it’s bulging to one side. Or today the shirt [the character is wearing] is one that he loves, but it’s been washed so many times it’s faded. There are those storytelling elements you have to use.

A lot of times, when people are photographed, they’re styled or they’re dressed by someone else. We don’t see them when they’re walking their kids to school or when they come in and unwind for the evening. We don’t know if they have favorite bunny slippers they put on. But we can take that artistic license as long as it falls within the storytelling.

In Selma (2014), it’s interesting how you put David Oyelowo, playing Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., in either two- or three-button suits, depending on the scene.

These people were wearing suits like we wear tracksuits. That was the mode of dress for the average guy in the civil rights movement. Also, they were garments of protest. They were trying to portray an image of nonviolence.

When I buttoned David’s shirt at its neck, I wanted to make sure it felt like the robust body that Martin Luther King had, where you saw a little flesh roll over the top of the collar. Some men like [the collar] a little loose because of the Adam’s apple, but his were always very tailored to his neck. There’s always this massaging going on…where you take what you’ve learned and take it into the story.

What did it feel like putting together The Art of Ruth E. Carter and seeing the story of your career?

I’m blown away! I’m like, how long have I been doing this? And this ain’t all of it! You mentioned Serenity, and I had totally forgotten about Serenity—and that’s one of my favorite projects.

It’s reaffirming that I was doing the right thing, way back then when nobody cared about costumes, and I was this young costume designer—Black, making my way through Hollywood. I was excited about the art and what I could do more than, oh, I’m going to be working with Denzel, I’m going to be around movie stars. So when I look back at the work, I see the dedicated artist.

SEE IT: Ruth E. Carter will appear in conversation with Amy Dotson at the Tomorrow Theater, 3530 SE Division St., 503-221-1156, tomorrowtheater.org. 7 pm Friday, March 8. $75.