“As a shop that has been almost secretive for five years in its operating, it’s a little terrifying to be in Willamette Week,” confesses artist and educator Sharita Towne, co-founder of nůn studios. “But I hope at the same time that the prints people have printed with us find good homes.”

Pronounced “noon,” nůn studios is a risograph printing collective. Towne started nůn studios in December 2019 as part of A Black Art Ecology of Portland, a multifaceted art project that has included a Portland Art Museum exhibition. Its first publication, Black Art Ecology Is Taking Place, was released the weekend before pandemic lockdowns in March 2020. While nůn studios has a rotating cast of on average eight artists at any time, including three artists in residence, the risograph printing collective celebrates five years together at the Portland Institute for Contemporary Art.

PICA’s lobby is currently hosting Grit & Grain, nůn’s retrospective featuring work by over 50 contributors, including guest collectives, visual artists and writers. Grit & Grain opened quietly by design on May 15, but closes with a bang on Saturday, June 14, amid fundraising efforts to collect over $50,000 for nůn’s ongoing costs and related community causes.

The studio’s name is a global word dating back centuries across several cultures. Towne explained nůn’s etymology in Arabic and Hebrew, while nůn co-founder Garima Thakur shared its significance in Hindi as a symbol of the sun and a half moon.

“It’s called chandrabindu in Hindi, which is the dot over the moon, which basically also means the sun, and we also found out that there’s a similar symbol in Arabic, which is basically like a vessel, and it’s also a hieroglyph for a snake, so we started looking at that as a symbol,” Thakur says over Zoom.

“The dot above [the u in nůn] is the incomprehensible, the unreachable,” Towne added.

Risograph printers were developed after the Second World War in Japan, combining elements of silkscreen and inkjet printing to be faster, more detailed, and more affordable in high volume than either of its predecessors. Riso, meaning “ideal” in Japanese, was a low-cost printer for businesses, schools and churches, but became popular in the 2010s among political activists for its ability to quickly produce a mass of vividly hued, richly detailed prints. Contemporary riso culture dips into the anarchist principles of glitch art and zine culture: using materials in ways they weren’t designed for to quickly inspire and inform the people.

Towne’s experience with risographs started by reading about the medium in online forums. Though risographs are commonly printed with soy-based ink, nůn’s ink comes from a waste byproduct of industrially processed rice, which is ultimately less ecologically taxing from an agricultural and recycling standpoint. Towne made a rhododendron pink by mixing orchid-tone ink with fluorescent pink, and a custom brown for a comic book by Melanie Stevens that Towne calls Donna Summer.

“That’s an example of nerding out way too hard on these dinosaur machines that shouldn’t do what we make them do,” she says.

Grit & Grain features three primary components. Accented by remotely placed kudzu vine installations in lobby and ceiling corners, Grit & Grain can quickly be broken down into categories of detailed “art” prints, thoughtfully designed text-based political activism signs, and a corner room hosting a risograph and digital projection piece by ilish bath. Digitized Hi8 home tapes play, looking back on bath’s parents in their youth. Watching the videos with her family proved unexpectedly depressive, bath says, as her parents reflected on the ways their lives did and did not pan out as expected.

“It was a way of observing how these moving images—still frames brought together—what that ended up doing to my parents and how it evoked an emotional response,” bath says.

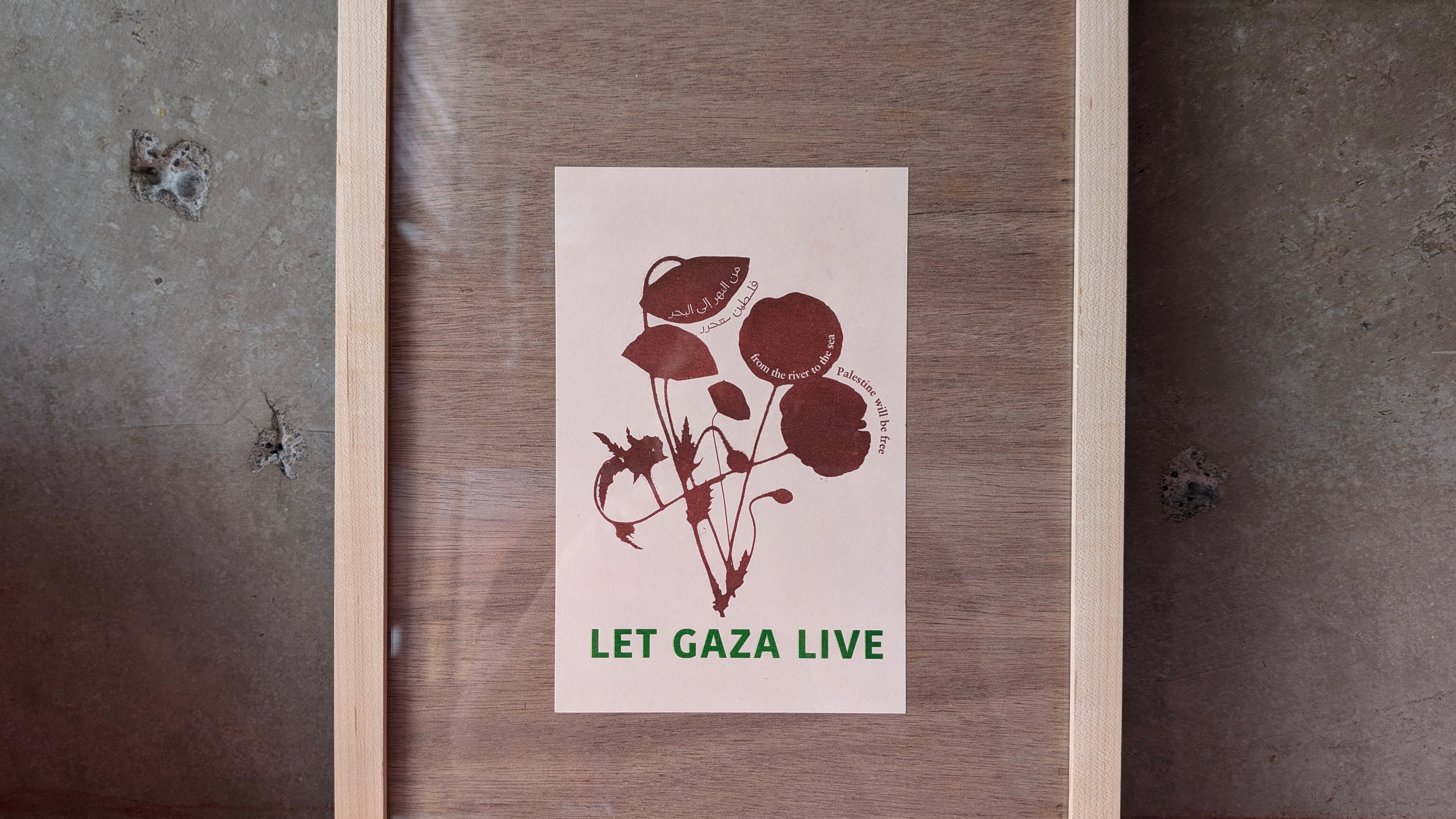

Pieces from Grit & Grain, including several in support of Palestine, showed last fall at the Northeast Portland bar and music venue Turn! Turn! Turn! on invitation from its then-curator. Around the first anniversary of the Oct. 7 attacks on Israeli civilians by Hamas fighters, TTT owner Mark Davies quietly took down a few prints by nůn members. When members of the studio learned from the curator about the predicament, nůn members arrived at TTT during a concert and took down the art show at intermission.

Though Davies met with Towne and other nůn members to discuss the situation in person, the show did not go on. But instead of calling for a boycott, Towne and nůn members continued ahead with their work.

“It’s really special to get to put up this show now,” Towne says. “We keep making things, so we didn’t want to have a ‘cancel move’ on the internet, we just wanted to keep doing what we do and just kind of celebrate the people we print with and for, so it’s nice to have this show up and not have that censorship.”

“Removing something is a political act unto itself,” bath added. “You can’t have political neutrality like that.”

For his part, Davies tells WW he regrets how he handled nůn’s art. A musician before buying the bar in 2024, Davies says he felt he and his now-former curator did not see eye to eye in their goals for the bar’s visual art wall, and the venue has since pivoted to showing work by TTT employees. Though he has hosted benefit shows for Gaza, Davies says he fielded complaints from Jewish neighbors ahead of the Oct. 7 anniversary about the pro-Palestinian artwork, which has a more lasting effect than a one-night concert.

“I hate what’s happening in Gaza and have no support for what Netanyahu is doing, [and] I understand to some extent why some people were upset with me just taking pieces down,” Davies says. “I still struggle with what I should have or not have done. In retrospect, I feel like I should have just let it be, but I was feeling uncomfortable with triggering anyone and, in the process, upset a lot of people.”

Towne clarified that PICA is hosting Grit & Grain as a Black Art Ecology of Portland project partner, not as a response to censorship, and that the show is funded by a Regional Arts & Culture Council grant. Grit & Grain’s closing reception on June 14 will feature Palestinian food, a DJ playing Palestinian music, and zines with prayers available to fold. Towne reflected on the ritualistic nature of riso for its intended and unintended purposes and how they still relate.

“There’s the funness of riso, but there’s also something more important to us. There’s a poetic to it,” Towne says. “When we print funeral materials, for example, there’s something so special about how this ink, which comes from waste from grain, we get to create the visual language for people’s grief.”

Correction: We have updated one of Thakur’s quotes to more accurately convey her intent, and clarified the communication between nůn studios and Turn! Turn! Turn!.

SEE IT: Grit & Grain by nůn studios at the Portland Institute for Contemporary Art, 15 NE Hancock St., 503–242-1419, pica.org. 2 pm Saturday, June 14. Free.