Spend a morning with Brad Ketch at Rockwood Community Development Corp. and it’s difficult to imagine him bilking Multnomah County by charging unapproved expenses and double-counting costs at the family shelter he runs in the Rockwood section of Gresham, one of the most disadvantaged neighborhoods in Oregon.

But that’s what the county accuses Ketch of doing. The county also alleges he billed for rooms that were closed for repairs, charged too much for maintenance, and hired a contracting firm owned by one of his employees. Earlier this month, the county’s Homeless Services Department halted payments for 50 rooms in Rockwood Tower, a repurposed Best Western that Rockwood CDC bought with a $7 million grant from the Oregon Community Foundation in 2021.

Ketch, 63, denies all the allegations. He says the county changed the terms of its deal with Rockwood and then came after him for reasons he doesn’t understand. And contrary to the county’s narrative, Ketch says it was Rockwood CDC that severed ties because the county owed it $1.1 million in overdue payments for housing families in need of emergency shelter.

“We know what it takes to run a safe and sustainable program,” Ketch says, sitting in the shelter’s cafeteria. “They are not willing to pay for a safe and sustainable program.”

The finger-pointing comes as the county seeks to improve oversight of the myriad contractors it taps to house the homeless, train unskilled workers, treat people who abuse substances, and perform every other human service in its purview.

County leaders have been under fire since 2024, when county auditor Jennifer McGuirk reported glaring flaws in contracting. Policies hadn’t been updated since 2011, and many county employees didn’t know what they were, McGuirk wrote. Worse yet, it had been five years since county workers had visited some of the nonprofits getting county money.

But in the case of Rockwood CDC, the county is coming on strong. The matter became public when county staff sent the list of allegations to reporters with a statement that the county had a responsibility to be good fiscal stewards of taxpayer dollars. According to the statement, the staff’s due diligence had revealed that Rockwood CDC was using those dollars improperly.

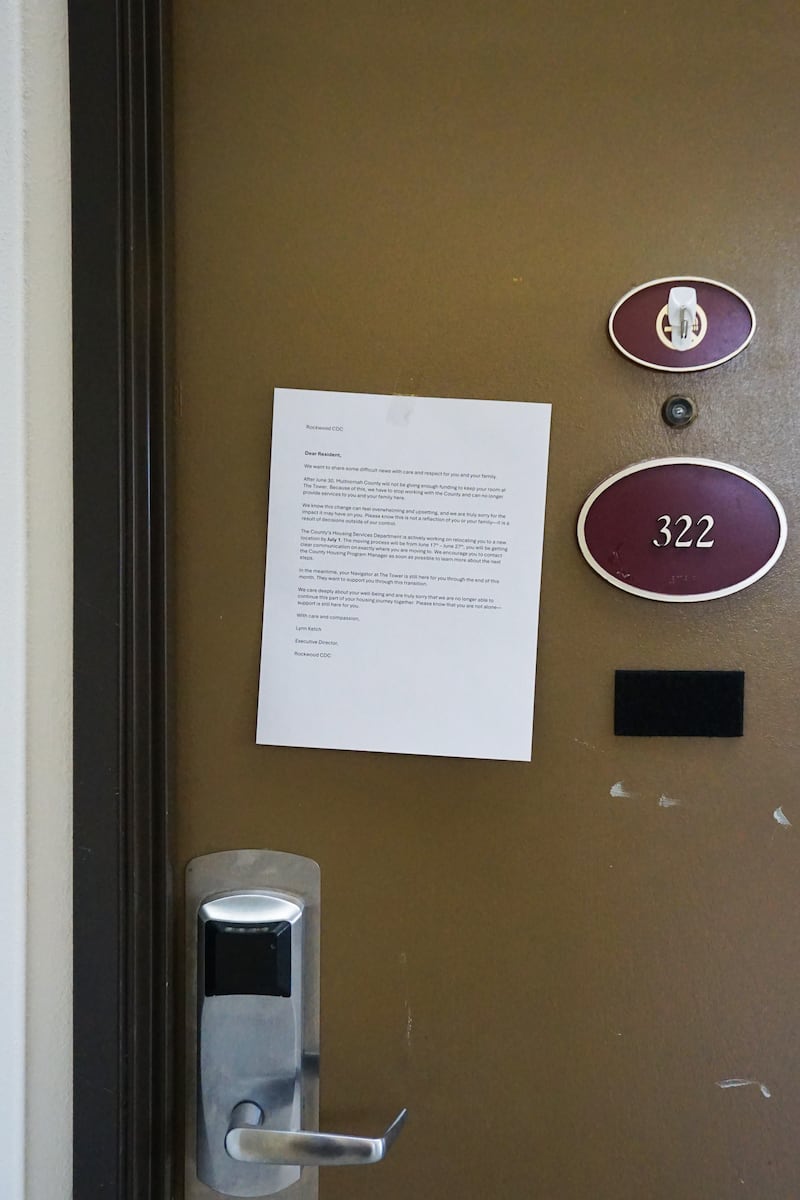

The fight has already claimed victims. Rockwood Tower staff taped notices to doors telling 40 families they had to move out by July 1. There are likely to be longer-term consequences, too. The county says Rockwood Tower accounts for almost half of family-shelter rooms countywide. The rooms are larger than most, and Rockwood uses bunk beds to fit a whole family into one.

Rockwood CDC has sheltered 449 families with a total 1,194 members since Rockwood Tower opened in 2021, Ketch says. It has served 634,014 meals and put 178 families into permanent supportive housing.

“We’re one of the largest service providers they’ve got,” he says.

Ketch has an unusual background for someone running a family shelter. Born and raised in East Portland, he graduated from Wheaton College, an evangelical Christian school in Illinois, with a bachelor’s in economics and business in 1984, and then added a master’s from the Kellogg School of Management at Northwestern University ten years later.

After working at larger companies, he became CEO of a tiny one called Rim Semiconductor in 2002. Rim was working on a computer chip that would speed data across copper wires, giving phone companies a way to sell faster internet connections over existing networks. Rim was odd, even among long-shot firms that trade for pennies a share, as Rim did. To raise cash for research, Rim (then called New Visual) produced a surf documentary, Step Into Liquid, that featured diehards riding waves in the Great Lakes, among other oddities. New Visual earned $287,570 from the film in its 2004 fiscal year and just $39,866 in fiscal 2005.

Shareholders in Rim, including Ketch, did something even more brazen in 2006: They filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission to sell 358 million shares of stock, even though Rim had lost $4.7 million in fiscal 2005 and a whopping $11 million in the first half of fiscal 2006. Worse yet, Rim said in the filing, “To date, we have not recorded any revenues from the sale of products based on our technology and have not secured any contracts to sell our products.”

Ketch says Step Into Liquid was in production when he joined the company. The stock sale succeeded and the technology worked, he says, but the company couldn’t survive the mortgage-market crash in 2008 and Great Recession that followed.

“I was cratered,” Ketch says. “I took a couple years off and gardened and got mad at God.”

His pivot into public service began with a call from a Morgan Stanley executive in Asia who asked him to take the helm of International Care Ministries, a nonprofit in Manila that uses private-sector business methods to help the “ultra-poor,” according to its website.

That stint was brief—just 11 months—and Ketch returned to the U.S. and started the Community Development Corporation of Oregon, Rockwood CDC’s parent, in 2013. ICM used a wraparound approach to poverty. Ketch hoped to do the same thing in Rockwood. Community Development has units that deal with nutrition, home ownership and language instruction.

It’s a family affair. Ketch’s wife, Lynn, is Rockwood CDC’s executive director. Their son Stephen is development manager.

Rockwood Tower is Ketch’s marquee offering. It sits next to a freight warehouse and has an Astroturf backyard where children play. The Best Western’s old pool is full and heated. Multnomah County began renting its rooms for homeless families in July 2022, taking 35 of the 65 available. After a successful run, the county took 15 more rooms in December 2023.

But last fall the partnership frayed. The HSD, then called the Joint Office of Homeless Services, reviewed Rockwood CDC’s finances in October 2024, according to a letter Rockwood sent to the county in March.

“From that review came troubling new requirements from JOHS which has compelled Rockwood CDC to seek counsel on how to make this relationship work for both parties as originally intended,” an attorney for Rockwood wrote to JOHS director Dan Field, who has since retired. “Without considerable progress on the concerns raised by this letter, Rockwood CDC is prepared to withdraw from its relationship with JOHS effective July 1 2025.”

Also, JOHS owed them $1.1 million on outstanding invoices, Rockwood said.

Rockwood lawyers wrote to Field and JOHS finance director Antoinette Payne two more times. Then the nonprofit called it quits in a letter on June 6. Attorney Kimberley Hanks McGair wrote that Rockwood had instructed her to commence litigation against the county for breach of contract, among other claims. “That lawsuit will be filed shortly,” McGair wrote. (A suit has yet to be filed.)

Jonathan Strauhull, an assistant county attorney, responded to McGair three days later, passing along the county’s regrets about the split. But, alas, the county didn’t owe Rockwood any money, Strauhull wrote. Rockwood sought $600,000 for a “room block agreement,” but they had no such agreement in the current fiscal year, so there was no debt.

As for the rest of the $1.1 million, the county owed none of that because Rockwood was “significantly noncompliant with the terms of the contract.” A bulleted list of “significant errors and inconsistencies” followed, including claims about overbilling and faulty accounting.

In an email to WW, a county spokesperson said the county had agreed to pay Rockwood $1.58 million “for the shelter” in fiscal 2025, which ends on June 30. The county allocated another $654,845 for “shelter diversion” services, including emergency financial assistance and case management to help families leave the shelter and return to housing.

In short, the county says it’s providing long-overdue scrutiny to a contractor that was overbilling for shelter. Ketch says the county got squirrelly when it saw how much sheltering homeless families really costs.

Whoever’s right, the upshot for 40 families is an unwelcome move. But Ketch sees value in the fight if it leads to better outcomes for his corner of Gresham.

“What if standing here with Oregon’s most dysfunctional government and having a train wreck is a necessary step to this community being transformed?” he asks. “If this journey with the county ultimately leads them to becoming more responsive to the needs of their citizens, I’ll do it.”