This story was a project of WW’s summer news interns: Seychelle Marks-Bienen, Senya Scott and Asa Gartrell. WW staff writer Sophie Peel supervised the team, contributed policy reporting, and wrote the story that follows.

Jamie Dunphy holds public office because Portland voters decided to give a damn about places like Gateway.

Nearly three years ago, voters tore city government down to the studs, partly in response to the argument that the city’s easternmost neighborhoods, long neglected, deserved a louder voice at City Hall. Dunphy was one of three councilors elected last November to represent District 1, which runs from 82nd Avenue to Gresham, and includes Gateway, a cluster of low-income neighborhoods that hug the east side of Interstate 205.

This month, he and his two colleagues in the district must confront a crisis that will test whether the new government can deliver for Gateway.

That crisis? A grocery store is closing.

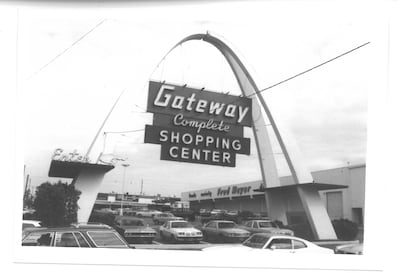

Not just any grocery, but the Gateway Fred Meyer, the cornerstone of a neighborhood defined by its asphalt parking lots and shopping plazas that increasingly stand vacant.

The 181,000-square-foot store has stood on the site since 1954, when Fred G. Meyer made it one of his first supermarkets in Portland. It is scheduled to shutter in September.

Many observers fear the area won’t recover from the gut punch. “The signal of what the disinvestment is going to look like is really bad,” Dunphy says.

To Dunphy, the closure is a damning reflection on the 25 years the city of Portland has operated an urban renewal area in the neighborhood.

In that time, the city’s economic development agency, Prosper Portland, has spent a total of $88 million trying to bring the neighborhood to life. Many living there say it’s now worse off than before.

The streets are lined with tents and tarps. The Gateway MAX station is frequented by people sleeping rough and others smoking fentanyl. Big box stores that once brought shoppers to the neighborhood have shuttered.

Dunphy, a frequent critic of Prosper Portland, says Gateway is an indictment.

“Everything that they promised in the beginning, almost none of it has been done,” he says. “Gateway is the biggest failure of the organization. The economic improvements are just simply nonexistent.”

Prosper tried to deliver those improvements through the same method it had used to resurrect the Pearl District and North Williams and Vancouver avenues, back when the agency was known as the Portland Development Commission. That method is called tax increment financing, and it’s most simply explained as a corralling of property tax dollars within a given boundary so they never leave the neighborhood. Prosper Portland borrows money against the expected tax receipts to fund local projects—everything from sidewalks to skyscrapers.

Gateway was the second place east of I-205 where Prosper tried to work its economic magic. (The first was Lents, 3 miles south.) By 2001, when it founded the Gateway TIF district, it was already under a microscope looking for signs of the unintended consequence of Prosper’s previous success stories: gentrification that pushed low-income residents and people of color to the fringes of the city by hiking property taxes. Prosper pledged to do things differently and try its best to keep current residents in the neighborhoods it was improving.

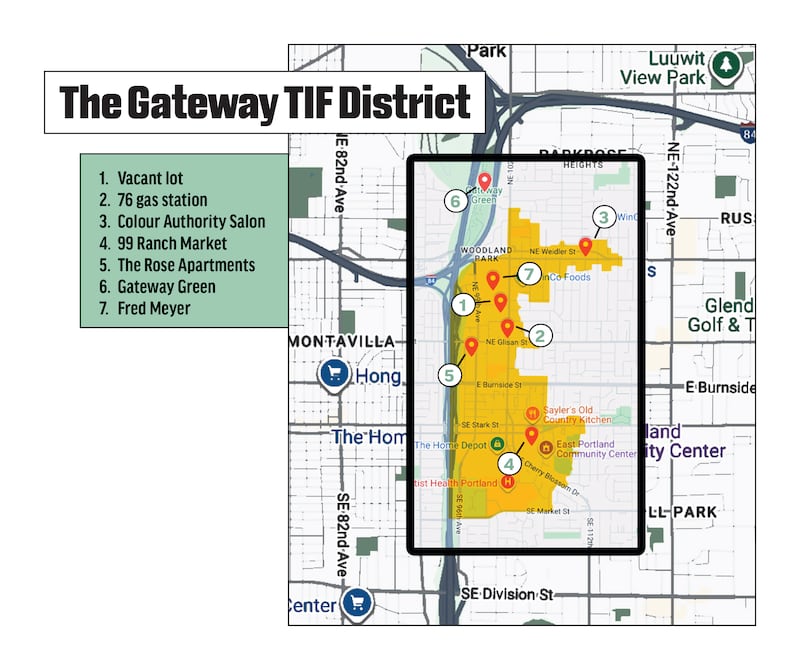

The place it chose, Gateway, comprised pieces of four neighborhoods east of I-205, including Hazelwood, whose western border runs along the highway (see map, below). Most of the selected area is dominated by shopping centers and medical offices. It’s where Portlanders from other neighborhoods visited to buy lumber, eat at Olive Garden, or get a colonoscopy.

In two decades, Prosper raised only $96 million in property taxes in Gateway—far less than in the other two TIF districts launched around the same time (Lents collected $262 million; North Macadam collected $311 million). So, in 2022, the Prosper board extended the life of the TIF district, this time pledging to spend $65 million over the next five years.

Prosper says it will continue collecting TIF revenues until it can pay back the maximum amount it has been seeking to borrow, which is $164 million.

“To achieve this, the expectation was the tax increment revenue would be sufficient to support this debt—meaning the base would grow at least 3% per year over the life of the district,” says Prosper spokesman Shawn Uhlman. “Since the projected revenue did not reach targets and the Board continues to support achieving district goals, the last date to issue debt was removed.”

City Councilor Candace Avalos says Prosper executives shared statistics showing that the percentage of residents that lived at or below the poverty line in Gateway was 19%, compared to 13% citywide.

By Avalos’ telling, Prosper saw a silver lining in that number. “It showed they were able to slow displacement,” Avalos says. “While on its face it looks like these communities are lagging behind, in actuality it shows that we were able to keep people.”

That’s one way to look at it. But it raises the question why the economic development agency would spend $88 million to not lift the economic status of Gateway’s residents.

Tim Zollbrecht is associate director of Portland Adventist Community Services, a church-run thrift store, low-income dental clinic, and food bank on Northeast Halsey Street. “It’s not like Gateway has completely dropped off the edge of the cliff,” he says, “but it’s stagnant. We’re just kind of here.”

To Zollbrecht, the closure of Fred Meyer feels like a bad omen. “If you don’t have the anchor, then what?” he says. “I’m not saying that all [the small businesses] are going to dry up and go away necessarily. But that’s a possibility.”

The decline of a neighborhood can be measured in many ways: by crime statistics, property tax receipts, or median income. We decided to measure the shrinking of Gateway by visiting seven of its places. Our reporters spent much of the past month speaking to people who have tried to maintain or revive specific properties. Their struggles speak volumes about how Prosper Portland failed to bring prosperity to East Portland.

To understand why the Fred Meyer is closing, you only have to look at the properties that surround it—starting right across the street.

Vacant Lot

837 NE 102nd Ave.

The grassy, fenced 5-acre lot that lies across from Fred Meyer has lain fallow for close to three decades. Many Gateway residents view it as the scourge of the neighborhood.

The man who owned it for most of that time says that wasn’t for lack of effort.

Ted Gilbert began assembling plots of land in 1998 that would eventually meld to become the 5-acre lot (“I had no plan; I just knew there was opportunity here”). Two years later, the Portland Development Commission drew a boundary around the Gateway area and pledged to turn it into a center of commerce for East Portland.

Gilbert was integral to the work group that Prosper formed early on to decide how to pour its resources into Gateway. “Holy cow, I came to be a believer,” Gilbert says from his office in a Victorian home in Goose Hollow.

Gilbert says he pitched Prosper on plans for his land for more than a decade. Nothing stuck.

One of Gilbert’s first pitches: a four-story building anchored by retail, including a bank and an ice cream parlor. Prosper had little money to offer. (It had recently used much of its first round of borrowing to help fund the development of the nearby Oregon Clinic, with its gastroenterology lab and cardiovascular center.)

So Gilbert pitched to private investors. He always heard the same sentiment: “But that’s East Portland.” Gilbert’s take is that “perception was holding back a willingness to take a risk and holding back private dollars.”

In 2018, Gilbert proposed combining his lot with an adjacent, vacant Elks lodge for a 10.5-acre project that would include an elementary school, a higher-education center, and a senior living community.

The David Douglas School District, which had purchased the Elks lodge in 2015, was sold on the idea. Prosper tentatively pledged $13 million. At a public meeting in Gateway in August 2018, then-Portland Mayor Ted Wheeler said: “I will not feel like my administration has been a successful administration for East Portland if we have not got this project off the ground. It’s very important to me.”

Nothing came of it. Prosper wrote in 2025 that Gilbert’s “project as envisioned was deemed infeasible.” The Elks lodge burned down in 2023.

Wheeler did not respond to a request for comment.

“Is anything on the books? I don’t see it,” Gilbert says, his face tightening to hold back tears. “Gosh, I get emotional about this.”

In 2023, Gilbert sold the land to developer Tom Cody for $11 million. Cody’s plans cratered, too. This spring, Prosper purchased the property for $10.6 million, with the clause that Cody has three years to buy back the property from Prosper and make progress building housing on it. If he doesn’t, Prosper will keep it.

In other TIF districts, Prosper often purchased vacant properties to ensure it had control over what happened on the land. It hasn’t regularly done so in Gateway. “Land banking on its own is very expensive and may not lead to development in TIF districts without significant investment from private entities,” Uhlman says.

For now, Gilbert’s scourge remains a scourge—just under a different owner.

76 Gas Station

515 NE 102nd Ave.

Muhammad Bhatti, Taser at the ready by his side, manages the 76 station as a part-time gig.

The store, Bhatti says, is often targeted for petty theft. A shrine to an employee of the store who was shot and killed in the parking lot in January 2023, Amado “Nacho” Santos, is adorned with flowers and prayer candles outside the front door.

“You call the police around here, they don’t show up,” Bhatti says. “They don’t seem that concerned about this area because they know so much shit already happens.”

Prosper recently paid for the Oregon Clinic—one of its proudest accomplishments in the district—to build a fence, hoping to deter vagrancy that seemed to migrate from the Gateway Transit Center onto the clinic’s property.

Hazelwood, the neighborhood that constitutes much of the Gateway district, was strafed by fatal shootings that ripped through East Portland during the COVID-19 pandemic. “I was looking at the homicide map just the other day, and I don’t think we’re No. 1 anymore,” a resident proudly reported at a recent Hazelwood Neighborhood Association meeting.

In fact, Hazelwood does remain in first place for shooting incidents, according to city data. Between July 2023 and July 2025, Hazelwood saw 135 shootings. (The second-highest neighborhood, Powelhurst-Gilbert, saw 119.) Hazelwood ranked first in car theft; second in robbery, burglary and assaults; and third in vandalism.

One deadly shooting occurred in January in the Fred Meyer parking lot. Jonathan Trent, 47, was trying to stop an armed robbery when he was shot. A teenage boy faces murder and robbery charges.

While Bhatti worries about Fred Meyer turning into yet another vacant lot that attracts drug use and tents, he can’t but admit that the closure might help his bottom line. “People might come here for more groceries.”

Colour Authority Salon

11121 NE Halsey St.

A quarterback’s throw over the Winco from Bhatti’s gas station is a mom-and-pop hair salon called Colour Authority.

Co-owner Tom Mahoney sips coffee on the back patio of the salon. “I think that the city has good intentions,” Mahoney says, “but they don’t follow through with what they say they’re going to do.”

Colour Authority sits along a stretch of small businesses sandwiched between Halsey and Weidler Streets. The two busy thoroughfares diverge at 102nd Avenue and join at 112th, forming an island of misfit shops between them.

Mahoney says he and other business owners watch out for one another. When the Jiffy Lube behind the salon abruptly closed three years ago, Mahoney persuaded the property owner to put up a fence, and Mahoney agreed to weed the property and keep it tidy to deter vandalism and camping. Valvoline moved into the space a year later.

“People do care about each other a lot,” Mahoney says. “But when something goes vacant, that’s when it really gets bad.”

King’s Omelets shuttered in 2022. Loving’s Salon, where longtime Gateway resident Linda Robinson says she got her hair cut for “years and years and years,” closed last year. (Her husband cuts her hair now.) The Gateway Area Business Association itself dissolved during the pandemic. The business association and King’s had received financial support from Prosper.

According to an ECOnorthwest study in April 2024, the number of small businesses in Gateway dropped between 2003 and 2019 from 376 to 324. It was the only active TIF district that had lost small businesses instead of gained them.

“Along with major structural shifts in the retail economy since the pandemic, safety and livability impacted major retail chains, small business, and residential communities,” Uhlman says.

In the absence of larger projects in Gateway, Prosper touts the grants and loans it’s made to small business owners and nonprofits. Over the past decade, Uhlman says, Prosper distributed $8 million in Gateway.

Prosper touts a recent streetscape project along Halsey and Weidler streets between Northeast 102nd and 112th avenues as an example of its work to bolster foot and bike traffic and slow cars. City bureaus spent a combined $7.3 million constructing bike lanes, adding crosswalks, and repaving. Business owners WW interviewed said the changes seemed to do little to slow cars, but did take away some parking spots, which affected some stores negatively. In response, Uhlman points to another ECOnorthwest study from 2022 that shows businesses along the couplet “in fact saw an increase in annualized sales volume from 2019 to 2022,” Uhlman says.

In 2021, Prosper gave Portland Adventist Community Services a grant to build a fence around the property. It bummed out associate director Zollbrecht, but the camping and trespassing had become disruptive.

“It seems like there are some smaller investments in the small businesses that are already here,” Zollbrecht says, “but not like, what are we going to do with that great big bottle of land that’s been sitting there vacant the whole time I’ve been here?” By that, he means the 5 acres Gilbert once owned.

99 Ranch Market

10544 SE Washington St.

The most excitement Gateway has seen in some time came with the advent of a new supermarket. The Asian grocery chain 99 Ranch Market opened an outlet last week at Plaza 205.

Plaza 205 sits next to the former Mall 205, now called Marketplace 205. It’s the other big retail anchor of Gateway’s TIF district. Marketplace 205 is no longer a mall; its tiled indoor corridors were closed to the public in 2022. It has hemorrhaged tenants: Pizza Schmizza, Bed Bath & Beyond, GNC, 24 Hour Fitness and, just this year, an office of the Oregon DMV.

Given the changes in American shopping habits, having Marketplace 205 as a neighborhood anchor presents a challenge. Gateway more closely resembles a suburb like Tigard than it does Portland’s inner neighborhoods. One block in Gateway is the size of multiple blocks downtown. The grid is built for transit by car, not on foot. All of these factors—plus a lack of basic underground infrastructure like water and electric hookups—made it harder for Prosper to remodel Gateway. Construction costs were sky high.

Shopping centers offer few trees and acres of asphalt, which means few “heat islands” are as broiling during a heat wave as the vast parking lots at and around Marketplace 205. But shopping centers also present the opportunity to buy dragonfruit, jujube and durians—or at least they do once 99 Ranch arrives.

The seafood and meat section near the back of the store, with huge glass tanks filled with crab and fish, already had a line forming to place orders. Produce signs had translations in Mandarin. A man loaded a Thai jackfruit, about 18 inches long, into his cart.

Pao Pharn, whose cart contained flour, apples and fish, says he would only occasionally visit the 99 Ranch in Beaverton. Now, he has one much closer.

“There is a lot of fresh seafood and veggies and fruit,” Pharn says. “There is a nice variety.”

The Rose Apartments

9700 NE Everett Court

At the corner of Northeast 97th Avenue and Everett Street stands the Rose Apartments, a four-story, 90-unit apartment building that offers half market-rate and half affordable housing.

Outside, 97th Avenue is lined with tents and RVs.

Gordon Jones built the apartments in 2015, receiving a 10-year tax abatement from the city. Seven years later, he was begging for an extension.

“The homeless situation on Northeast 97th and 99th avenues has been consistently horrendous. We’ve lost many tenants due to the horrible situation around the area and turnover has been high,” Jones wrote to a Portland Housing Bureau manager in September 2022. He wrote a similar email in October 2023, citing “burned-out cars, camping everywhere, garbage strewn all over, camp fires burning in many places.” (WW observed similar conditions this month.)

But what upsets Jones most isn’t the condition around his apartments. It’s that the city refused to help him build more of them.

In 2019, Jones and two other major landowners in Gateway—Andy Baltz and Joe Westerman—presented a sweeping plan to Prosper called “Livable Gateway.”

The three met with Mayor Wheeler and his Housing Bureau director in February 2019 to pitch 2,000 units of new housing between East Burnside and Northeast Glisan streets and 97th and 100th avenues. The developers pitched a 10-year property tax abatement for the units. They would then pay tax on all units—affordable ones included—“thereby generating additional fiscal revenue that would not occur for an entirely affordable project,” the group’s pitch deck read.

The group asked for $150,000 per affordable unit from the city—for 800 units, that comes to $120 million. The remaining 1,200 market-rate units, the developers pitched, they’d pay for privately. The plan was dead in the water by the following year. “I lost all interest in working in Portland after all this,” Jones says.

In Jones’ eyes, the biggest problem is that few of the large investments Prosper made—The Nick Fish, a 75-unit mixed-income housing building, for instance, and the expansion of the MAX Green Line to Clackamas—generated any significant tax revenue.

“Tax increment financing districts fail when you only build buildings and projects that are not on the tax rolls,” Jones says. “And that’s the road the city went down, in my opinion.”

Indeed, recognizing a need for more-affordable housing, the City Council passed a policy in 2006 requiring that 30% of TIF dollars be set aside for the creation of deeply affordable housing with a focus on tenants making 0-60% of area median income, or AMI. In 2015, the council increased the set-aside to 45%.

As with Gilbert’s lot, Prosper replies that investors lacked “access to capital sufficient to develop large sites.” Prosper Portland says the criticism by Jones and other developers puzzles them “given the amount of energy and resources spent working with local developers and landowners.”

Westerman, who owns six adjacent blocks, says Prosper shut down every attempt the Livable Gateway team made to partner on ambitious developments.

“This is a public-private endeavor, and if it becomes 100% public, then it becomes the projects. You need both,” Westerman says. “Talk is cheap. And Prosper Portland is full of it. Gordon spent a lot of time and a lot of money to have Prosper look him in the eye and say no.”

Jones moved to Sisters in 2023. Westerman, now 72, put all of his Gateway blocks—totaling 27 tax parcels—up for sale last year. Still, he drove from his sprawling farm in Gresham to his properties on 99th and Davis to speak with WW, even though it was a phone interview. He just wanted to look at them.

“I feel hope sitting here,” Westerman says. “There is darkness before the dawn. I think the sun is going to rise over Gateway. You’ve got to think that way.”

Gateway Green

Along I-205 bike and pedestrian path

Another ribbon of hope is the 25-acre bike park called Gateway Green that unspools along the rolling hills between freeway interchanges. It was the brainchild of an unlikely duo: Linda Robinson, a Gateway resident who sat on Prosper’s Gateway advisory committee for many years, and Gilbert. The two secured funding from Portland Parks & Recreation and the regional government Metro to build the sprawling park in 2017. They used no tax increment financing; the bike park lies outside the urban renewal district.

On a recent July afternoon, hard rock blared out of a speaker at the top of the pump track, where a group of seven BMX bikers waited their turn to hit the string of steep jumps below. Riders shot 6 feet into the air, some doing tailwhips. KC Badger is a former pro BMX biker and comes to the Gateway skatepark four days a week. He says Gateway is “now a destination of sorts” for BMX bikers. “The best thing that this place has was made by volunteers,” he says.

Fred Meyer

1111 NE 102nd Ave.

For many of the refugees who arrived in Portland over the past two decades, the Gateway Fred Meyer was their introduction to America.

Employees of the Immigrant and Refugee Community Organization would escort their clients to the supermarket to buy necessities with government vouchers, says IRCO manager Maryoris Pedroso-Reyes. “The first store they would go to to shop for clothing was Fred Meyer.”

Although IRCO’s office lies only two blocks south of Fred Meyer, Pedroso-Reyes started walking her clients the long way around in recent years. She wanted to avoid tents and erratic behavior.

“For my refugees, their main concern is safety,” Pedroso-Reyes says. “Most of them have fled from countries in war, so when they hear about shootings, trauma comes to life.”

The killing of Jonathan Trent was the most alarming incident in a wider trend of crime around the grocery. Fred Meyer responded to frequent shoplifting by closing off exits and creating barriers around sections of the store.

That’s a turnoff for shopper Ambrose Austin. “It’s weird to shop somewhere where it feels like a police state, where you have to show your receipt on the way out,” he says.

Still, news of its closure hit residents hard. “It’s absolutely devastating,” said one man loading groceries into his pickup truck on a recent weekday. “I woke up in a cold sweat. This is the worst.”

District 1 City Councilor Candace Avalos is adamant that the sale is an opportunity.

“Let’s be real: people in Gateway have already been shopping at Winco, because it’s way more affordable than Fred Meyer,” she wrote on Bluesky in July. “But this is not the time to just let the area slip further!”

She was criticized for sounding cavalier. At a recent meeting of the Hazelwood Neighborhood Association, board member Jackie Putnam said: “I’m extremely frustrated with our councilwoman and her comment regarding the closure of Fred Meyer. She’s completely naive about what goes on in our district.”

Avalos acknowledges that what she said upset some people, but sees it differently.

“They thought I was being flippant. I was like, some people might see this as a loss, I see this as an opportunity,” Avalos tells WW. “Freddy’s doesn’t care if they leave behind lost jobs and empty buildings. This is why we need to talk about how we have community ownership of these assets.”

The Gateway Shopping Center, which includes the Freddy’s, a now-vacant Kohl’s storefront, Ross Dress for Less and Office Depot, is on the market for $50.8 million.

Prosper says purchasing Fred Meyer isn’t on the table. “Investment in additional land acquisition would limit the amount of TIF funds (both housing set-aside and non-set-aside) available to invest in the district for actual build-out of temporary uses, housing, and mixed-use development,” Uhlman says.

Mayor Keith Wilson’s office met with PacTrust representatives this summer, after the closure announcement. It’s not clear what—if anything—came of that conversation.

“The city is committed to working collaboratively with District 1 city councilors, Prosper Portland, TriMet, private property owners, and community members to shape the area’s future,” a spokesman for the mayor, Cody Bowman, says. “As an immediate step, the mayor’s office is bringing together key partners to explore strategic investments, support current tenants like the Oregon Clinic, and unlock new opportunities for public and private sector development.”

At a July meeting of the Hazelwood Neighborhood Association, 12 attendees sat around Methodist church dining tables and wrung their hands. They, too, mused whether the city could buy the Fred Meyer building. A Prosper Portland employee chimed in.

“I would like to continue this conversation,” said Joel Devalcourt, a project manager, “but tonight I’m not in a position to have answers.”

To association board member Bob Earnest, that’s what Prosper Portland has been telling the Gateway neighborhood for the past 25 years.

“We’ve been ignored for so long,” he said.

Clarification: A previous version of this story stated that 99 Ranch was located at Marketplace 205. In fact, it’s located at Plaza 205, a shopping center adjacent to Marketplace 205.