Like many eighth graders, Lola thinks a lot about high school. An avid dancer, she’s leaning toward enrolling at Jefferson High School in North Portland, a school known for its strong dance program. She has pored over the curriculum, emailed the school’s artistic director, and was so excited about a field trip to the school everybody calls “Jeff” that she could hardly sleep.

And yet.

“She’s torn,” says her mom, Kristen Jessie-Uyanik. “She wants to go to Jefferson, but she is under the impression, and she’s probably not far off or wrong, that she is the only one [who wants to go] among the people she knows best.”

Jessie-Uyanik is white and lives in the Sabin neighborhood in Northeast Portland. Lola’s friends are likely all going to Grant High School. Since its rebuild and reopening in fall 2019, Grant has become Portland Public Schools’ highest-enrolled high school. Currently, it enrolls 2,074 students, well above its intended capacity of 1,700.

That’s more than five times the enrollment of Jefferson, PPS’s least-attended high school. It currently has just 391 students across its four grades.

Part of the reason so few students currently attend Jefferson is because they, like Lola, may choose to go elsewhere. Since 2011, a dual enrollment policy has allowed students living inside Jefferson’s historical attendance boundary to opt in to one of three other high schools (see “Choose Your Own Adventure”). And those other high schools were more alluring, especially because they’d received renovations.

The result? In the 2025–26 academic year, 1,351 high school students residing in Jefferson’s dual assignment boundaries opted to attend another school in Portland Public Schools, according to the district’s enrollment summary by neighborhood. That left Jefferson, the only historically Black Portland high school, with a cratering enrollment.

Jefferson’s facilities are about to receive a $466 million update, courtesy of voters who passed 10-figure school bond measures in 2020 and 2025. But the enrollment problem remains.

Without a large influx of students, the district can’t provide comprehensive programming at Jefferson, the only major Portland high school without standard high school Advanced Placement or International Baccalaureate coursework, and with fewer electives than its counterparts. (see “School Rivalry”).

The Portland School Board charged the superintendent in 2022 with developing a plan by 2027 to fill Jefferson in preparation for its grand reopening. Given how few families have chosen to send their kids to Jefferson, school district officials have decided to stop offering them a choice.

For months, district officials have crafted new maps that divide North and Northeast Portland elementary and middle school students among Jefferson, Grant, McDaniel and Roosevelt high schools. (They plan to start filling the school with the high school class of 2031, today’s seventh graders.) Superintendent Dr. Kimberlee Armstrong released her recommended plan last week. The School Board votes in January.

In between, Portland Public Schools waits to see how parents swallow the news.

The toughest crowd the district must persuade? White parents in relatively affluent neighborhoods like Jessie-Uyanik’s, where going to Jefferson has never been part of the plan, and where private school is a real option.

The irony is not subtle: As PPS tries to fill its historically Black high school, it will largely have to woo white parents to send their kids there. The campaign to persuade them has revealed several uncomfortable truths about how race has shaped Jefferson’s trajectory. It has led to tough conversations at dinner tables and PTA meetings about what Jefferson’s success will require.

And it has illuminated the unspoken but very real power white parents wield in school districts like PPS.

Lakeitha Elliott, a longtime Jefferson advocate who was part of the class of 1994, says it’s been frustrating to watch parents fret in the redistricting conversation about what Jefferson doesn’t have.

Choose Your Own Adventure

“You question why folks are OK with those disparities in a school where our kids are, but they usually don’t challenge them until there’s a possibility that they might be on the end of the stick that doesn’t have the stuff,” Elliott says. “No one pays attention to why Jefferson students aren’t getting access to these things until it’s like, ‘Oh, wait, my kid might have to be impacted by that.’ Then suddenly there’s more outrage.”

Sondra Cozart knows all too well what happens when a high school enrolls just a fraction of the students attending the other eight. Her son’s a senior at Jefferson who just this year couldn’t enroll in a construction course because there weren’t enough students to merit paying a teacher to teach it.

“It makes me really upset because they’re drawing away from Jefferson to benefit these other schools,” she says. “Jefferson should be getting a full breadth of the same opportunities that all of these other schools are getting, and that’s not happening.”

Cozart, who attended Jefferson herself as part of the class of 1985, says she remembers a time when Jefferson had AP classes and endless electives. She says dual enrollment is a “terrible idea” that has done nothing but contribute to the “dismantling of Jefferson.”

It’s not the first time. Ethan Johnson and Felicia Williams wrote in the Oregon Historical Quarterly how the school had trouble attracting students, particularly white students, from its feeders in the 1960s and ’70s. Parents “deliberately ignored attendance boundaries,” they wrote, and sent their kids elsewhere.

A string of policies allowed Jefferson students to choose other schools starting in the 1980s, causing further harm. This all happened as the core of the historically Black neighborhood of Albina was gutted by construction of Interstate 5, Legacy Emanuel Medical Center, and Moda Center, only exacerbating the situation.

“The ability of our city to grow and thrive and develop over decades has been on the back of Albina,” says School Board member Rashelle Chase-Miller. “The roads that we travel, the arenas that we go to for entertainment, hospitals that we go to when we’re sick or to have our babies. That was built on the back of Black Portland.”

And Chase-Miller says she spent much of her childhood squaring her own understanding of Jefferson—as a vibrant place where many from her family graduated and she attended plays and Jefferson Dancer shows growing up—with the broader Portland community’s understanding of the school.

“The narrative from outside our community was that Jefferson High School and the neighborhood that I lived in was dangerous, that it wasn’t a good school, that all it had going for it was dance,” she says. “With those ideas come the ideas that the kids are also those things: that they’re not intellectual, that they’re not learners, that they’re not academics.”

The consequences of the enrollment problem are stark. There are 11 electives offered at Jefferson, compared with 29 at the three other schools that participate in dual assignment. Jefferson offers two career and technical education courses, compared with 11 at Grant, 10 at McDaniel, and nine at Roosevelt. It has no Advanced Placement courses, compared with 17 at Grant, 25 at McDaniel, and 14 at Roosevelt. (Instead, Jefferson has a partnership with Portland Community College across the street, allowing students to take some advanced college coursework.)

Sammy Pitchford, a freshman at the University of Portland who spent a large portion of her high school years at Jefferson, had a front-row seat to the school-to-school disparities. While she went to Jefferson, her twin sister attended Grant. “I would come home so angry I would literally be crying to my mom about how unfair it was,” Pitchford says.

Cozart says ending dual assignment is long overdue.

“If the school is full, all of the programs that are traditionally at Grant or at Roosevelt or at McDaniel will be available to the students at Jefferson,” she says. “You get the AP classes back. You get all of that at Jefferson if you have the enrollment to bear it out.”

Portland voters passed the 2020 and 2025 PPS school bonds with about 75% and 60% voting yes, respectively—effectively mandates to rebuild the school. But for some parents in North and Northeast Portland, the buy-in to Jefferson’s success will require more than just filling in the right bubble on a ballot. And when it comes to volunteering their children, those values become murkier, and the story gets more complicated.

In seven interviews with parents who oppose sending their kids to Jefferson, each one told WW they wholeheartedly support the school’s success. But for many of them, the redistricting conversation is a sticking point.

In the case of Denise Bilbao, it’s where her liberal values meet her children’s education. And she says she has no intention to send her kids to Jefferson.

Bilbao is a parent of an eighth grader and sixth grader who lives in the Sabin neighborhood. She understands that the district is in a tough position, and acknowledges that the school is in its current situation because of systemic racism. “That’s undoubtedly the case,” she says. “They’re trying to fix an injustice that’s 60 years old.”

Bilbao moved into Grant’s boundary after her family heard good things about the school—it’s walkable, it offers more courses. If the boundaries change, she’s a renter with the mobility to allow her children to attend Grant if they want, or perhaps another school. (Her older son is part of the presumed last class with a choice, but he’s trying to get into Benson Polytechnic High School.)

“There are lots of ways to battle racism,” says Bilbao, a single mom and full-time physician. “Is my kid’s education the way I want to do that? It isn’t. It’s the thing I value most in life that I want to leave the least to chance. Is it my job to throw my kids in there and let them flounder? I just don’t feel that obligation.”

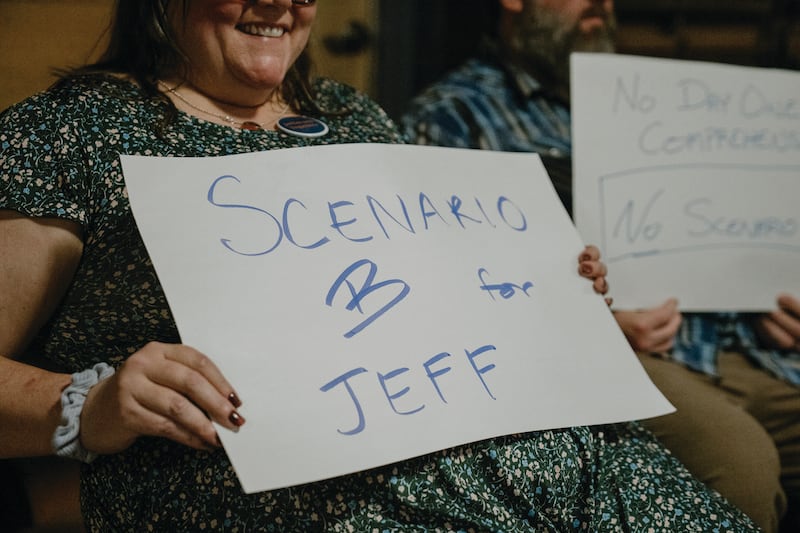

She’s not alone. For weeks, some families at Irvington and Sabin elementary schools have organized strong opposition against those two schools ending up at Jefferson.

A slice of parents has made it clear that, if the choice is ultimately Jefferson or bust, they will take their kids elsewhere—including private schools. An informal poll of about 120 families, conducted by parents organizing the Sabin and Irvington opposition, found about 69% are unwilling to consider Jefferson. (As one parent said, “If I’m going to drive my kids to school, let’s look at other options.”)

None of the parents who spoke to WW about their opposition to the plan said they had any concerns about their children attending a largely Black high school. (In fact, many of them worried that pulling Sabin and Irvington students from Grant’s boundary would effectively make that high school less diverse.) Bina Patel, a parent of color who has a seventh grader at Tubman and lives in Sabin, says calling all criticisms racist obfuscates real concerns she says she has about sending her child to Jefferson. And she says some parents she knows are scared to speak out for fear they’ll be labeled as racist.

“What I see is a lot of white people calling a lot of other white people racist. And I think there’s just a lot of white guilt in Portland,” Patel says. “Racism is a convenient excuse to silence people.”

Instead, those families say there are a host of other reasons why they’re concerned about Jefferson. Some are worried about the school’s current facility and lack of comprehensive offerings, or say the route to school isn’t walkable and would involve crossing major streets, posing safety issues. Many note that Sabin and Irvington were only added to the Jefferson dual assignment zone in 2018—when PPS turned K-8s into elementary schools and was on a quest to fill Harriet Tubman Middle School—and were not part of Jefferson’s historic boundary but Grant’s. And there’s a community aspect many of them emphasize: Many say they built their lives, including where they bought homes and where they volunteered, around their children attending Grant.

But more than a dozen people who support sunsetting dual assignment tell WW that race and class feed into the concerns they’ve heard, just in a more subtle way. After all, Jefferson was long deprived of resources in large part because of its Black student body and Title I status. And now white parents in nicer neighborhoods are reluctant to experience the same deprivations.

A parent of color at Faubion PK-8, who declined to use his name because a family member is employed by the district, said what others only whispered off the record.

“I am not the kind of person that likes to ever point out people’s racism,” he says. “I don’t think it’s just about people being afraid of Black people. Parents could be afraid of what it means to be in a place where people are treated like Black folks. They think, if I’m in this school, my kid is going to get only the resources that are available in this place.”

Addie Humbert, a mom of a seventh grader at Ockley Green Middle School who’s supportive of the transition, says there’s a flip side to that coin: Wealthier parents can help a long-neglected school get more resources.

“You will use your very powerful voices to fight for staffing and funding at a state and local and school level,” she said in her Dec. 8 School Board testimony addressing some families opposed to redistricting. “And that work will benefit not just your kid, but a community that has been desperate for resources for decades.”

Bilbao agrees that as the district tries to right its wrongs, it should look beyond catering just to “privileged people.” But she says if the district is trying to get her excited about Jefferson, it needs to get more specific to lower the anxieties of concerned parents. She wants timelines and numbers around questions like how the district will scale up teachers and course offerings.

“You can entice with a stick or a carrot,” she says. “A stick is what’s being used right now.”

Even parents who support sending their kids to Jefferson say the district could have done a better job of easing parents’ concerns. “I think some families are asking, ‘I understand how this will benefit Jefferson, but how will it be better for my student?’” says Molly Fitterer, who’s looking forward to sending her Tubman seventh grader to Jefferson.

Pitchford, the University of Portland student, says Jefferson has plenty of strengths the district should sell more aggressively. She says the partnership with PCC prepared her for college in ways AP courses would not have. And the tight-knit community is one that “doesn’t let anyone slip through the cracks,” she says, noting how supported she felt working through her mental health challenges.

And for many parents of middle schoolers, the boundary changes come as another unexpected hurdle in a rocky path for their students at PPS. Those parents have navigated everything from the COVID-19 pandemic to the teacher strike to broken promises at their elementary and middle schools.

Eloise Koehler, a parent of a sixth grader at Tubman and two younger kids at Irvington Elementary, says she heard a lot about how the district did not deliver on promised support in Tubman’s early years. “I am very worried that they are going to build the building and leave the Jefferson leadership and staff and current students on their own to figure this out,” she says. “There’s no organization that doubles its size without additional resources.”

That’s why she is one of several parents at the Tubman Parent Teacher Student Association who have spearheaded a “Tubman to Jefferson Transition Team,” meant to mobilize parents early on to hold the district accountable for its promises. If most—or all—of Tubman is headed for Jefferson, she says it’s imperative parents direct their time to ensuring that the school gets everything it needs.

Nichole Watson, the district’s senior director of family and community engagement, tells WW she agrees information and follow-through are paramount. “When we show up the way we say we’re going to show up,” Watson says, “it is another tenet of rebuilding trust with the community.”

As PPS tries to fill Jefferson, and works to draw more families to fill its halls from the broader Portland community, it also must balance what the existing Jefferson community—and the generations of people invested in the high school—want to see for the school.

Jeremiah Morris, a freshman at Oregon State University, cemented his sense of identity at Jefferson. Morris originally tried to enroll at Grant. But on a bus ride home from football practice, he ran into a Black student who told him that it took her an entire year to make a single friend at Grant. “When I quoted that for my father,” he says, “that’s when he immediately stopped trying to get me into Grant and took me to Jeff.”

Morris says it was important for him to attend a school that emphasized cultural diversity; he says forging friendships with all types of people helped him realize his ambitions. During his time at Jefferson, he took courses in biotechnology at PCC and received certifications in skills like CPR. Now he’s majoring in bioengineering in hopes of working for the World Health Organization to engineer vaccines, working toward preventing diseases internationally.

He says it’s “inevitable” under the district’s plans that Jefferson will get whiter, and that losing some of the diversity the school is known for will be “a little bit hurtful.” He says it’s important PPS does not push out families of color in the process—Jefferson’s curriculum has long emphasized Black history, alongside Hispanic, Native American and Asian history. He urges that curriculum stay put.

Elliott, the longtime Jefferson advocate, also says it’s crucial the district not lose sight of the families for whom Jefferson means the most.

“Are you building it in hopes that white families will come in and access this?” she says. “Or are you building this because you want to honor the tradition, the connection, and because you want a high-quality school in every neighborhood?”

At the Dec. 8 board meeting, Nnenna Lewis, a 1998 Jefferson graduate and mom to a senior at the school, said the Black community has endured many hardships to benefit Portland, and now it’s time parents leverage their socioeconomic power to help Jefferson win.

“Your kids will grow up to be our police officers...and when they pull over a young Black man, what is that relationship if they can’t sit in a classroom with them?” Lewis said. “You want to say you want Jefferson to win, but the only way for you to do that is for you to stand up and walk with us across the line.”

For her part, Koehler is on board.

The mom of three has done a lot of reflecting since the district announced its intentions to end dual enrollment, especially about whose voices should be heard. She says it shouldn’t take white families believing in Jefferson to ensure the school’s success; her goal with the Tubman to Jefferson Transition Team is to listen to and advocate for what the Jefferson community says it needs.

Koehler’s had to sit with the anti-Jefferson rhetoric she’s heard from parents in opposition: comments about the school being unsafe or about what it doesn’t have. She’s thought about why she didn’t think about the resource disparity before. “What about the 400 kids there right now?” she says. “What if we advocated on their behalf?”

At a recent meeting of the Portland School Board, Koehler grappled with those questions in her public comments, reading a letter she’d written to herself. In it was an acknowledgment that her Oregon history lessons had omitted the reality of segregation, that her own great, great, great grandfather had supported segregated schools. “You inherit that whether you want to or not,” she said.

When she heard that more than 100 Irvington and Sabin families had signed a petition to keep themselves in the Grant boundary, she said she “felt angry and ashamed, and yes, superior because you said you would never do that,” she continued.

“But you have to be honest, Eloise, you’re not that different. You moved to Irvington partly for the schools. You didn’t ask why Jefferson didn’t have IB or AP until it affected your own kids,” Koehler told a packed board room. “And you’re not saying this to beat yourself up. You’re saying it because you finally understand how your choices and your silence fits inside a much bigger story.”