Engedaw Berhanu says he will always remember the night his nephew, Mulugeta Seraw, was murdered.

It was just before dawn on Nov. 13, 1988. The phone rang in San Francisco—and Berhanu learned Seraw had been hurt in a fight in Portland.

"I knew immediately something had gone terribly wrong, because Mulugeta was never a fighter," Berhanu says. "Also I knew that someone wouldn't call me at 5 am if he was just injured."

Berhanu got on a plane to Portland. He arrived at Emanuel Hospital hours later, and learned of his nephew's death when a doctor spoke to him as if Berhanu already knew.

Eight years earlier, Berhanu had helped Seraw, a fellow refugee, travel from war-torn Ethiopia to the lush haven of Portland. With the swing of a baseball bat, Seraw's journey was over—and Berhanu was left with anguish.

"That," Berhanu says, "was the worst news I ever got in my life."

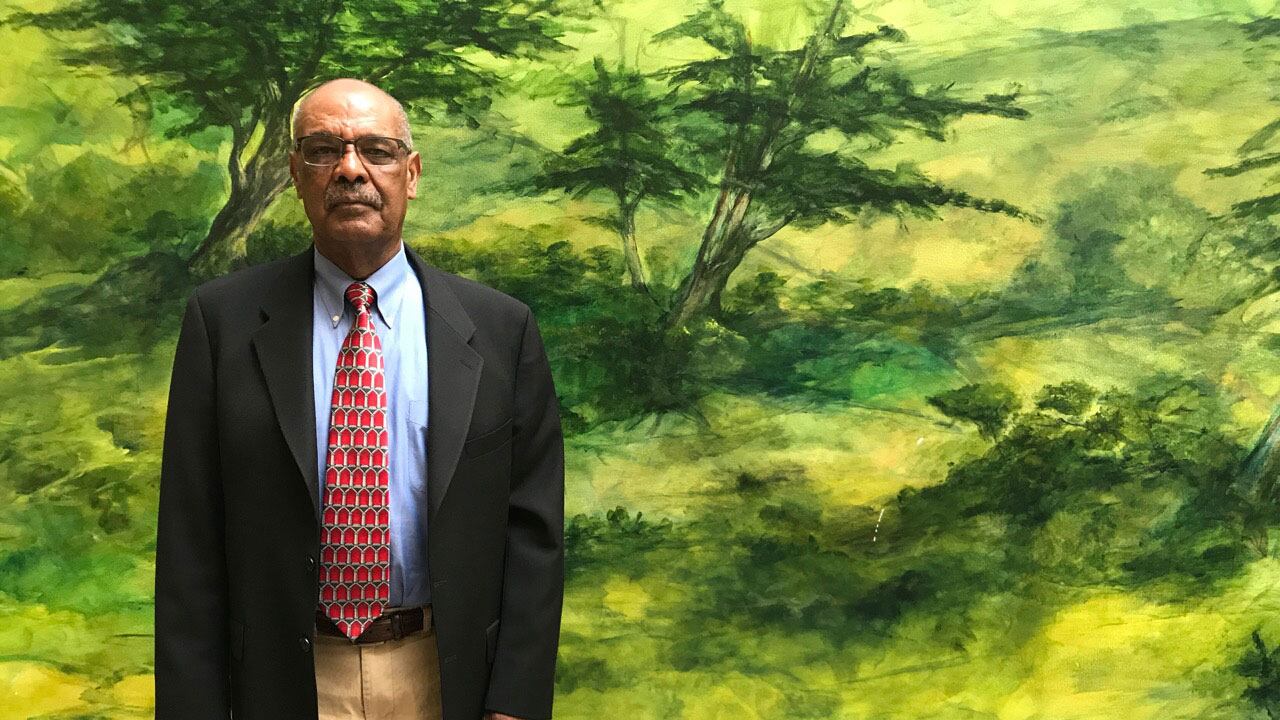

Still living in the Bay Area, Berhanu, 71, says he thinks about Seraw and his death every day. And as he looks around at the United States in the Trump era, he wonders whether any lessons were learned.

"I think we are in a bad place, worse than ever before," Berhanu says. "I don't want to be political, but the political environment we are in today, our president, the way he carries himself, the racist remarks he has made, his gestures…" He trails off.

"When Mulugeta died, I was ignorant about this stuff," he says. "Ignorance is bliss."

On Nov. 13, Berhanu will speak at the Urban League of Portland's commemoration of Seraw's death, held at a hotel near Portland State University. He has never before attended such a ceremony for his nephew.

"Every time I talk about him, I know I am going to be emotional," Berhanu says. "But I want as many people as possible to know about him, and to know who he was."

Berhanu came to the United States from Ethiopia in 1972 as a student. He moved to Portland in 1979, and then Mulugeta came in December 1980, also on a student visa. The two men lived together for two years—first in Beaverton and then in Portland's Buckman neighborhood.

"When I decided to move to California, I asked him if he wanted to move with me," he recalls. "He said, 'No, I am happy here. I have my circle of friends. I love it here. I can look after myself.'"

Endayehu Kendie, who came to Portland in 1979, was one of those friends. She remembers that in 1980, "when [Seraw] arrived, [Berhanu] had a welcome party for him. He was very well-liked."

Then Seraw was murdered, by members of the East Side White Pride skinhead gang. The death was horrifying to Portland's Ethiopian community, then relatively small and mostly students.

Kendie recalls Portland suddenly seeming like a dangerous place. "Other Ethiopians around the country were talking about Oregon as a hateful state," Kendie says.

For the next two years, Berhanu worked not only to hold the murderers responsible, but those who had stoked their hateful ideology.

He called a lawyer he knew—who put him in touch with Alabama-based civil rights watchdogs at the Southern Poverty Law Center. Together they launched legal actions that would constitute one of the most resounding blows ever dealt to the white supremacist movement.

After killers Kenneth Mieske, Kyle Brewster and Steve Strasser pleaded guilty, the SPLC's legal team launched a civil suit against White Aryan Resistance leader Tom Metzger—arguing Metzger was vicariously liable for the killing because he sent an agent to Portland to encourage skinheads to assault immigrants.

"Metzger's agents encouraged them to be violent, and my nephew was killed in the process," Berhanu says. "We thought he should be held accountable."

During the trial, he says, "no one [in] the Ethiopian community showed up for the hearing—I think they were scared."

Seraw's family was awarded $12.5 million. The Southern Poverty Law Center collected more than $100,000—including Metzger's house. Most of that went to Seraw's son, Henock, who is now a commercial airline pilot.

"I didn't get a red penny," says Berhanu. "I did it for my nephew's honor."

Over the years, he's had second thoughts about the course of action he and the SPLC pursued.

"I tend to agree with Elinor Langer's conclusion in her book, A Hundred Little Hitlers," Berhanu says. "She says we should have gone to trial [for the skinheads] and not allowed them to plead guilty, because a lot more would have come out in the trial. Things were swept under the rug."

His greater awareness of American racism is just a small part of the impact that Seraw's death had on Berhanu.

"His death is the most bitter event in my life," he says.

The Urban League's commemoration, however, gives him a chance to reflect on the "positive story" of Seraw's life before his murder.

"I am proud of him, and I will always be proud of him. I still miss him to this day. I will miss him for the rest of my life."

GO: The Urban League of Portland hosts the Mulugeta Seraw Commemoration Conference at University Place Conference Center on Tuesday, Nov. 13. 9 am. Register at ulpdx.org.

The nonprofit WW Fund for Investigative Journalism provided support for this story.

Engedaw Berhanu Remembers His Nephew—Brought to Portland, Then Forever Lost

Here's What Happened the Night Mulugeta Seraw Was Murdered—and Afterward

WW's Reporting on How Hate Spread Across Portland In 1988

The Reporter Who Investigated Mulugeta Seraw's Murder Says the Hate Was Homegrown