Not long before the pandemic, Portlander Irene Taylor met a friend for drinks downtown and heard a story that blew her mind. The friend knew someone whose full-time job was to take calls from men who were sexually abused as kids in the Boy Scouts.

There were so many victims, she said, a Pearl District law firm had hired a social worker to help with the deluge of calls from broken men.

“I really thought about that—40 hours a week, all you do is field phone calls about men who were once boys, who were abused by one organization,” Taylor says. “How does that keep you busy for months and years at a time, full time?”

Taylor is an award-winning documentary filmmaker, and she had to know more about the strange and awful job. She met the woman, Michele Limpens, who works for the law firm Crew Janci, and Taylor was soon chasing her next project: a riveting documentary that premiered nationally last week at the Tribeca Film Festival and debuts June 16 on Hulu.

Leave No Trace centers on the Boy Scouts of America’s centurylong cover-up of sexual abuse and the Oregon case that blew it wide open.

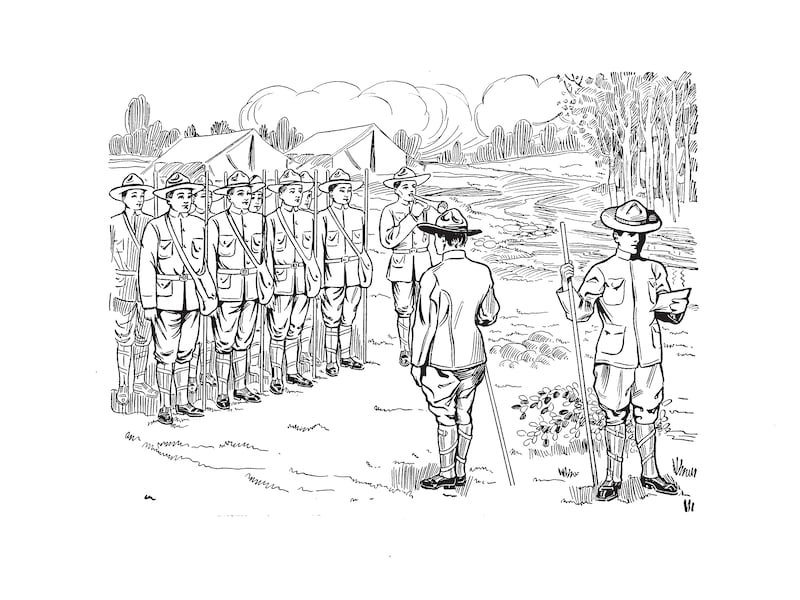

It reveals how an institution that’s as American as a Norman Rockwell painting became a playground for pedophiles, with a record of abuse that surpasses that of the Catholic Church but has received much less attention.

The film spotlights survivors’ quest for justice as they seek acknowledgment from the Scouts for shattering their lives. It prominently features WW reporter Nigel Jaquiss, who was a producer on the film and acts as the movie’s narrator from the dual perspective of a former Boy Scout and an investigative reporter.

The movie got made by a dream team of local journalists after weeks of reading disturbing documents, taking red-eye flights to tearful interviews, and receiving a dash of good luck.

“It was clear the Boy Scouts wanted the world to believe that most of the abuse happened a long time ago and the problem was taken care of,” Taylor says. “But the numbers told a different story—a darker narrative about American boyhood.”

A dry business article in The New York Times caught Jaquiss’ eye in February 2020. The Boy Scouts of America had filed for bankruptcy in anticipation of what it then expected to be a couple thousand sex abuse lawsuits.

But as headlines about a new coronavirus dominated the news cycle, the country seemed to miss the gravity of the story. It was Jaquiss’ first clue the subject might be ripe for investigation. “Nigel sort of marveled that it wasn’t a bigger story,” Taylor recalls.

The two, who met at Columbia Journalism School in the mid-’90s, discussed it as a possible project over virtual coffee in July 2020. Taylor told Jaquiss about the social worker she’d met, and they agreed to look into it together.

They both had day jobs, so the work began as an after-hours inquiry. Taylor, 52, is usually drawn to character-driven human interest pieces. Her Peabody Award-winning 2007 documentary Hear and Now, for example, follows her deaf parents as they get surgical implants.

Jaquiss, 59, meanwhile, gets a rush from holding power to account and reporting on the workings of complex institutions. His reporting that exposed former Gov. Neil Goldschmidt’s sexual abuse of a teenager, for example, won him a Pulitzer Prize in 2005.

“We realized this story was an intersection of what we both do best,” Taylor says. “We wanted to know how pedophilia had been allowed to run rampant inside this organization for so long.”

Jaquiss dug into public records and quickly discovered “a huge Oregon angle,” he says. A direct line appeared between the 2010 case of Kerry Lewis, a sexually abused former Portland Scout, and the institution’s financial downfall.

“That case was a gigantic boulder that rolled downhill and landed on the Scouts,” Jaquiss says. “It crushed them.”

As Jaquiss pored through files from the Boy Scouts’ bankruptcy filing, Taylor courted two important allies: Stephen Crew and Peter Janci. The lawyers, operating out of the Albers Mill Building, had worked the Lewis case and represented hundreds of other victims who allegedly suffered sex abuse in the Boy Scouts. She asked if they knew any survivors who wanted to tell their story.

Over the next several months, the law firm connected Taylor and Jaquiss with five survivors scattered across the country—with the caveat that interview subjects could “back out at any moment,” Crew says.

“It takes tremendous courage to come forward,” Crew says. “Surprisingly, they were comfortable with it.…They were impressed with the seriousness of the film.”

That fall, nine months after the Scouts filed for bankruptcy, The New York Times reported that far more than a few thousand men, and even some women, had come forward alleging sex abuse at the hands of the Boy Scouts, which started allowing girls to join in 2019. There were at least 82,000. They ranged in age from 8 to 93, the paper reported.

“The numbers were mounting,” Jaquiss says. “It’s such a hellacious story we knew other people were going to be on it. So the question then became, are we going to get beat?”

In November 2020, Taylor drove down Interstate 5 to the town of Lebanon for her first on-camera interview with a survivor, Kris Yoxall.

Yoxall, 18, is a slender, flannel-clad skater kid. As the camera rolled, he opened up for the first time, in front of his parents, about the sexual abuse he suffered four years prior.

Yoxall was preyed on by his scoutmaster, Douglas Young, when he was in his early teens. Young, who is now incarcerated at Ontario’s Snake River Correctional Institution near the Idaho border, was convicted of sexually abusing a total of 10 boys.

Taylor could sense they were onto something big—and deeply disturbing.

She treaded lightly. “I leaned on my instincts as a mother,” says Taylor, who has three sons, two of whom were in Boy Scouts.

“I’m used to talking to boys, and I know that if you can just hold your tongue, there’s a lot of really good information that comes out,” she says.

The film opens with a shot of Yoxall in his modest, poster-dotted bedroom. There’s a hole in the wall that he made with his fist. “I hate that I do it,” Yoxall says of his outbursts.

Yoxall is one of six sex abuse survivors the movie centers on while tracing the arc of the Boy Scouts’ scandal and financial collapse.

Over the next year and a half, Taylor and Jaquiss spoke to dozens more sources and conducted emotional, hourslong interviews with survivors in Florida, Colorado, Indiana, Texas and Arkansas.

Taylor sometimes felt spiritual and intellectual fatigue. “This sounds melodramatic,” she says, “but one of the biggest challenges was just waking up each day and needing to deal with this topic for two years.”

Repeatedly, she and Jaquiss would hear variations on what Kris Yoxall’s mother said in a heartbreaking early interview. “I feel like a fool,” she sobbed. “The Boy Scouts have known for so long that this stuff happens—and they haven’t done a damn thing.”

There’s a reason journalists like Taylor and Jaquiss know the vast scale of how many kids were preyed upon by scoutmasters: the case of Kerry Lewis.

Scouting had established deep roots in Oregon—thousands of members in councils and districts all over the state, 800-acre Camp Meriwether on the Tillamook County coast. But Oregon was also the scene of a trial that would lead the Scouts to financial ruin.

In 2010, a Portland jury found that Timur Dykes, an assistant scoutmaster from Portland, sexually abused Lewis. Dykes had previously confessed to a Boy Scouts coordinator that he had molested 17 children—yet was still allowed to work in the organization, according to Lewis’ attorneys.

In the punitive phase of the trial, the jury awarded Lewis $18.5 million, the largest single payout in a child sex abuse case in U.S. history.

That the trial happened at all was highly unusual. The Boy Scouts were regularly sued but very rarely went to trial, choosing instead to settle cases. That tactic often ensured that the Scouts’ “perversion files,” records of pedophiles within their ranks, remained secret.

During the Lewis trial, Judge John Wittmayer ordered a portion of the perversion files released. The vast dossier detailed the abuse of thousands of boys between 1965 and 1985.

“Kerry Lewis was the genesis of those files becoming public,” says Crew, who worked on the case.

The ruling was, effectively, game over for the Boy Scouts.

After the massive Portland verdict, sexual abuse attorneys across the country could point to the dollar value of damage done to a single Portland Scout, and they could introduce the files that were translated into searchable databases by newspapers that included The Oregonian and the Los Angeles Times.

Costly cases against the Scouts piled up around the country. In response to the scandals in the Catholic Church and the Boy Scouts of America, many states, including Oregon in 2015, extended the statute of limitations for civil lawsuits for sexual abuse.

Prior the Kerry Lewis case, the Boy Scouts’ annual tax returns show the organization regularly earned an operating profit. But in the decade between losing in Portland and declaring bankruptcy in 2020, the organization lost money every year, a total of more than $500 million.

Jaquiss says he tried for months to get Boy Scout executives involved in the documentary. “We really wanted to know, how are you thinking about this now?” But he ran into one dead end after another.

Some knowledgable sources would talk off the record and point him in the right direction. But they didn’t want to go on camera.

So Jaquiss was thrilled when John Stewart, a former managing director for the organization, agreed to talk.

In May 2021, after a road trip from New York to Ohio, Jaquiss and Taylor met Stewart in Indiana to interview him. Jaquiss expected the executive, who resigned in 2019, to speak from a marketing perspective, possibly about how the institution could be restructured.

But, over a pre-dinner drink, Stewart casually mentioned that he too had been abused as a Scout. “That was an amazing moment,” Jaquiss says.

Stewart appears in one of the movie’s most jaw-dropping scenes, detailing the sexual abuse he suffered at a camp in Frankton, Ind. His older brother, he says, narrowly escaped a similar attack.

“I remember him telling me a story about his scoutmaster coming into his tent one night, and he just basically said, ‘Get off me,’” Stewart says in the film. “An adult volunteer did a very similar thing to me, and unlike my brother, I didn’t have the strength or ability to push him off.”

The rise of streaming video services in the past decade gives filmmakers more opportunities to tell difficult stories. But in this case, the story was about an institution with close ties to many corporate boardrooms.

Taylor had plenty of contacts in the film world after working with HBO for years. But early in the production process—back in 2020, in fact—she encountered a problem.

Randall Stephenson, then CEO of AT&T, which owned HBO at the time, had been on the Boy Scouts’ national board since 2005, including serving as president from 2016 to 2018. “We couldn’t really pitch to HBO, the best and most likely outlet to buy it,” Jaquiss says. “It would be a big conflict.”

Enter Ron Howard. The Hollywood executive formerly known as Opie co-runs a production company called Imagine Entertainment. Sara Bernstein, Imagine’s co-president of documentaries, was intrigued by the fresh angle on the Kerry Lewis trial.

“I was like, OK, there’s something really unique here,” says Bernstein, who had previously worked with Taylor at HBO.

In early 2021, ABC News Studios and Hulu signed on to the project, hoping to compete with HBO and Netflix in the crime documentary field that had exploded while people sat on their couches during the pandemic.

By January 2022, Taylor and Jaquiss were done filming and had completed most of the editing. That month, they submitted the documentary to the Tribeca Film Festival.

Last week, they flew to New York City for the film’s world premiere. The Wall Street Journal called Leave No Trace “superbly conceived” and “not to be missed.”

On June 8, Taylor arranged a private screening for survivors and their families at ABC’s New York headquarters. Boy Scout executives heard about the screening and asked to be invited. Taylor shut that idea down in a hurry—some of the survivors would be seeing the film for the first time, and the last thing they needed was for representatives of the organization that failed them to be in the room.

The people who participated in the movie’s creation hope it serves as a warning to other powerful bodies.

“The real tragedy would be if other organizations don’t learn from this,” Janci says. “I hope other folks learn from the Boy Scouts’ mistakes.”

In the future, the Scouts may be replaced by a new outdoor group for kids, Taylor says: “It’s my hope that another organization will pop up in its place.”

The new group could teach the same values of self-reliance and honesty, along with the Scouts’ own “leave no trace” philosophy—to leave a place better than you found it.

“I don’t know if the Boy Scouts’ brand will survive,” she says. “But it’s my hope that the ideal will.”

SEE IT: Leave No Trace streams on Hulu starting June 16.