On the afternoon of Sept. 28, Talmage Ellis became the latest victim of the years of violence plaguing Dawson Park. Portland police say Ellis, 57, died after a man chased him down with a knife and repeatedly stabbed him.

A killing is not unheard of in the North Portland park that’s been ravaged by gunfire in recent years. But Ellis’ death was unusually troubling to the Eliot neighborhood, for two reasons.

First, he was well known in the Black community as a mentor to young men involved in gangs or at risk of joining them. As a young man himself, Ellis was in a gang and brawled with members of rival gangs. He’d spent nearly 20 years in prison because of it, receiving a 10-year sentence for attempted murder in 2002. After he got out of prison for the second time in 2011, his work with young people signaled a redemption.

Second, Ellis was killed in a park where he’d spent 40 hours a week in recent years on a city contract, mediating disputes between parkgoers that may have otherwise escalated into fights. By the count of the nonprofit he worked for, Ellis deescalated over 50 such disputes.

To Lionel Irving, a close friend of Ellis’ and the executive director of Love Is Stronger, the gun violence prevention nonprofit Ellis worked for between 2021 and 2023, his death is made more painful by its location. Ellis’ death was a stark reminder that Dawson Park is still in the throes of violence.

“It’s a sad day for the city and for the Eliot neighborhood. He built bridges between neighbors and the park,” Irving says. “Talmadge should not have died in that park.”

For decades, the Eliot neighborhood felt as if city officials had abandoned Dawson Park. It had become a hotbed of drug dealing, gun violence and prostitution, but little was being done to fix it. That was in part because officials feared the perception that they were overpolicing a park with historic significance to Portland’s Black community.

After significant media attention on the park, including a WW cover story (“The Trouble With Dawson Park,” Sept. 14, 2022), city officials took notice.

The city increased the number of events held at Dawson, hosting job and resource fairs. It also hosted kid-friendly events meant to bridge the gap between parkgoers and neighbors, like the “Dawson Park Play Dates.”

City outreach workers began visiting Dawson and the area around it on a daily basis. The city installed bollards on the streets surrounding the park to prevent cars from parking there—a means to discourage drug deals. The Portland Police Bureau held targeted missions to “concentrate on individuals known to frequent the Dawson Park area and are connected to ongoing investigations,” city spokeswoman Mila Mimica says.

In 2022 and 2023, Ellis and Irving were part of the city’s solution. The Office of Violence Prevention paid Irving’s nonprofit, Love Is Stronger, to spend time at Dawson Park mediating disputes. (The city says it paid $377,029 for six months of that contract.)

“He was instrumental. He was at Dawson Park for eight hours a day,” Irving says. “You could put him in the hottest area. He is our No. 1 gang veteran as far as escalation of gun violence.”

KGW-TV quoted Ellis in a June 2023 story about Dawson Park.

“I’ve sat down with a lot of different gang members and rivals who didn’t get along with each other and I’ve mended it. I have gotten them to come together and become as one,” Ellis told the television station at the time. “Dawson Park is really the only park that deals with African Americans and at-risk youth. So one of my angles is to try to change some of the thinking of our youth.”

By Irving’s telling, the park was slowly becoming safer in the year Love Is Stronger worked there. (Irving says he and Ellis did the same work in their free time before the city paid them to; Ellis used to grill for parkgoers on the park’s public grills after his 2011 release from prison.) “Man, we had Dawson peaceful,” he says. Data from the city is ambiguous. In 2021, there were two shooting incidents in Dawson Park. The following year, in 2022, there were five. In 2023, that dropped to two; in 2024, it increased to six incidents.

Despite the city’s increased efforts, the violence was stubborn. Eighty shots were fired at Dawson Park in the summer of 2024, in an incident that left one seriously injured and another, Ronald Davis, dead. Davis, 66, had been a regular at the park, often playing dominoes with other older men around the picnic tables. Parents of children attending the nearby Montessori school, Arc-en-Ciel, penned a letter to city officials at the time, begging them to do more.

“The city’s total abandonment of Dawson Park and the surrounding blocks,” parents wrote, “is a tragedy for the entire community, not just our children.”

On Sept. 25, just three days before Ellis’ death, police say a drive-by shooter fired into the park. The Portland Police Bureau said in a release it didn’t know the intended target, nor was anyone injured in the shooting.

Jeremy Duke, who lives in the neighborhood and whose 4-year old son attends Arc-en-Ciel, wrote in a Sept. 26 letter to area elected officials about hearing the shooting while picking up his son.

“We dodge ambling, intoxicated individuals walking directly down the middle of the street. We pull around the haphazardly parked cars with their doors open, full of people buying, selling, and consuming drugs,” Duke wrote. “And sometimes, like yesterday and in July of 2024, we duck and cover.”

Meanwhile, the city had switched contractors for violence deescalation at Dawson Park. In 2023, the city concluded its contract with Love Is Stronger and hired a violence prevention nonprofit called Nurture, which has a three-year, $3.1 million contract with the city to perform similar work.

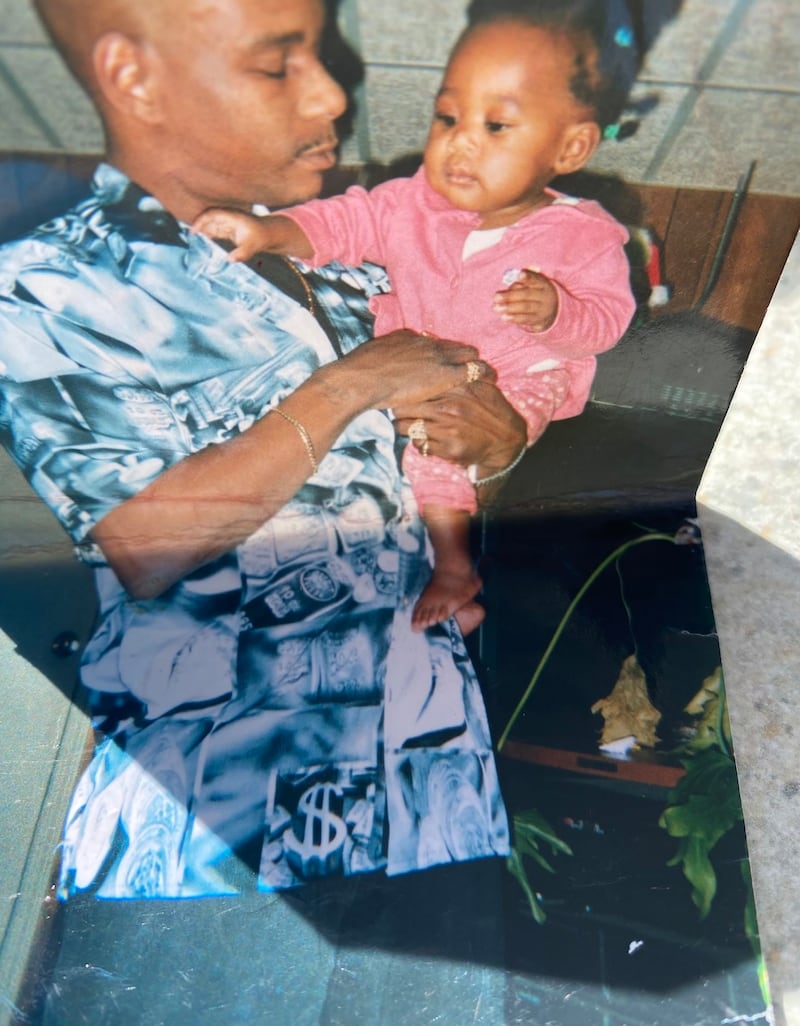

Even after Love Is Stronger was no longer on the city dime, Irving says, Ellis would visit the park to deescalate violence anyway. Tashauna Ellis, Ellis’ 24-year old daughter, says the same. But in recent months, Tashauna says, her dad stopped visiting Dawson Park because the violence had gotten so bad.

“We’ve all been wondering why he was there that day,” she says.

What happened Sept. 28 is laid out in a probable cause affidavit written by Multnomah County deputy district attorney Brian Davidson.

A witness reported he and a group of friends had been approached by a man, later identified as Jermaine McKenzie, who “was acting oddly and eventually was ushered away from the group by an unknown person who had also been in the park.” The witness “heard disturbance in another part of the park and turned to look. He observed McKenzie chasing an unknown individual around a parked car. McKenzie had a knife in his hand. McKenzie eventually caught up with the unknown individual and stabbed him repeatedly,” the affidavit explains.

It’s not clear if the unknown person who tried to guide McKenzie away from the group was Ellis, but it’s implied in the affidavit. A woman drove him to nearby Emanuel Hospital, where he died shortly thereafter.

A Multnomah County grand jury indicted McKenzie on Oct. 6 on charges of second-degree murder and unlawful use of a weapon.

According to Mimica, Nurture “has a staff member assigned to Dawson Park Monday through Friday.” But Ellis was killed on a Sunday—and no one from Nurture was at the park. “An outreach worker from Nurture, who was off the clock but had already planned to be in the park for a community grilling event, arrived before other organizations, shortly after the stabbing occurred,” Mimica said.

Irving has hard feelings about Love Is Stronger losing the contract to work in Dawson Park (the nonprofit recently received a contract to do similar work in another part of the city), but he’d still frequent it. That changed when Ellis was killed. “I grew up in Dawson Park,” he says. “I took my son there to play about a month ago. I can’t imagine myself going to Dawson Park again.”

Ellis spent years behind bars for two separate convictions, the latter of which was attempted murder in 2002. Tashauna visited him regularly in prison as a kid during his second stint, but her fondest memories of her dad are when he was first released when she was 11 years old. At the time, she says, Ellis knew how to cook only one thing for her: fried fish sticks in the oven.

Ellis moved back to Portland and in 2019 opened up a food cart with his brother called Ellis’ Style Louisiana Burgers. That would later turn into Papa’s Soul Food Kitchen, a cart at the east end of Northeast Alberta Street best known for its fried fish sticks. He also opened up the Sideline Social Lounge, a low-key bar at the same location.

“Nobody had that type of influence like Ellis,” Irving says, “where you could have rival gang members inside the same club and have no conflict.”

He spoke openly about his time spent in a gang, his daughter says. “He told me that he really regretted it,” she says. That, as much as anything, may explain why he kept going back to Dawson Park.

Nearly every weekend up until Ellis’ death, Tashauna and her half-brother, 9-year-old Kyngston, would spend the weekend with Ellis. He’d cook whatever they asked, or they’d go to Qdoba for dinner. They’d rent a movie to watch. He’d make them omelets in the morning.

“He was very nice and very courageous,” she says. “He was always willing to help anyone.”