Portland Parks & Recreation faces a maintenance backlog of as much as $800 million in no small part because the bureau built new facilities—at least twice at the behest of political leaders—but didn’t plan for how to maintain them.

That’s what the Portland city auditor concluded in a report released today.

“We found that Parks has not developed the plans necessary to fund critical services and amenities in the long term,” city auditors wrote.

The parks bureau didn’t have a “long-term fiscal sustainability plan” that would have exposed “impending funding gaps before they became a crisis,” auditors wrote.

And an “infrastructure crisis” has arrived, the audit says. In September 2024, the parks bureau reported that 86% of its property and assets were in poor or very bad condition and that it would cost between $550 million and $800 million to repair them.

The audit largely echoes reporting by WW in 2023, which described how Portland Parks & Recreation rapidly expanded despite already having more assets than it could afford to maintain.

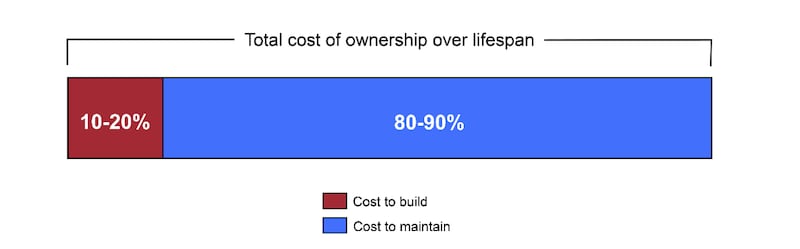

Throughout the 17-page report, auditors hammer parks leaders for poor planning and reveal seemingly obvious management mistakes, like building parks without accounting for their upkeep. A diagram included in the audit shows that construction accounts for just 10% to 20% of the total cost of owning a park during its lifespan, while maintenance accounts for 80% to 90%.

Poor planning has made the parks bureau vulnerable to political pressure, the audit says. In 2023, before the structure of Portland city government changed, the commissioner in charge of the parks bureau directed staff to invest in University Park, “even though staff had not identified it for investment consideration.”

University Park is in North Portland. Auditors didn’t name the commissioner who directed the investment. Dan Ryan oversaw the parks bureau for all of 2023.

A year earlier, Mayor Ted Wheeler allocated $500,000 from his budget to build a new skatepark and pickleball courts near Laurelhurst Park to block tents, the audit says.

“Neither of these projects had Parks director approval, which was required through Parks process for investment decisions at the time,” auditors wrote. “While construction was funded, these new assets will add maintenance costs over time.”

Some of the bureau’s woes stem from a strait-jacketed funding method, the audit says. Much of the money for parks comes from system development charges—one-time fees on construction of new houses and other structures that pay for public infrastructure.

The parks bureau is in a bind because, by law, it must spend any SDCs that it collects, but they may not be used for maintenance, the audit says.

“SDCs make it difficult for Parks to take a level of service approach, because they must build new assets even if doing so undermines long-term sustainability,” auditors wrote.

Another structural problem: City bureaus may prioritize building new amenities if they make the provision of services more equitable.

“This equity exception lacks clarity,” auditors wrote, “because it does not define any aspect of equitable provision of services or specify whether it should be based on racial demographics, community-specific engagement, spatial distances to assets, or another measure.”

In response to the audit, interim parks director Sonia Schmanski said she agreed with six recommendations aimed at improving the bureau’s performance. They include developing a fiscal sustainability plan; communicating the scope of cost-saving actions to the public; and establishing systemwide goals for levels of service.