In most American cities, property taxes are less complicated than particle physics, or string theory. The same is true in Portland, but just barely.

But the current City Council may be the first one ever to ask administrators to come explain it, according to Multnomah County Assessor Mike Vaughn. He and John Botaitis, the county’s head of appraisals, answered an invitation by City Councilor Olivia Clark to do so on Oct. 16.

In an interview, Clark said she arranged the session to bring “greater sensitivity” to downtown businesses. “It’s really important,” she said, “that people understand how local government is funded if we’re going to pay for the programs that people want throughout the city.”

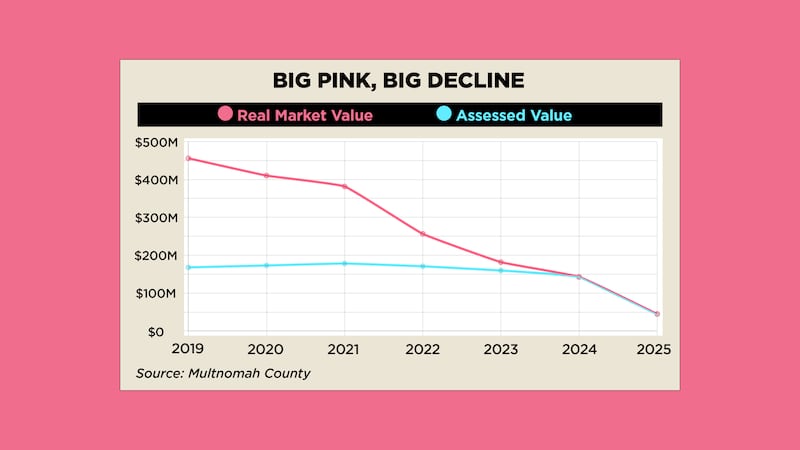

Property generates about half the tax revenue collected by the city every year. Councilors—many of them socialists who want to expand the city’s safety net—got a rude awakening last July, when the U.S. Bancorp Tower, nicknamed Big Pink, sold for just $45 million, down from the $373 million that Swiss bank UBS Group AG and Seattle-based Unico Properties paid in 2015.

That sale reduced the amount of tax the city can collect on the 42-story building by a whopping 68% from $2.7 million in 2024 to $860,297 this year. Gone in an instant was almost $2 million that could have been spent on public safety or to bolster Portland Street Response.

That part of property tax calculation is simple. It gets more complicated when you consider that the sale of a marquee property like Big Pink becomes a data point for the county assessor’s attempt to determine the value of property held by 300,000 accounts. With a staff of just 160 assessors and appraisers, Vaughn can’t send someone to inspect every property, so he relies on math.

Atop all that work, Vaughn’s staff must deal with commercial property owners who see Big Pink’s decline and appeal their own valuations. In 2018, when Portland was still Portlandia, Vaughn’s office fielded 277 petitions from owners of industrial, commercial and multifamily properties. Last year, they got 722.

When petitioners win, they get refunds. Including residential appeals, those totaled $3.2 million in 2018. They jumped to $18.3 million in 2023. For 2024, refunds could reach $30 million when they’re all resolved, Vaughn’s staff says.

All that, even, is easy to understand compared with the concept of “compression,” a term of art that describes how declining property values shrink tax collections in a system like Oregon’s.

The Beaver State’s taxes were pretty straightforward until 1990, when a Gresham health club owner named Don McIntire won passage of Measure 5, capping the amount of tax paid on any Oregon property at $15 per $1,000 of real market value—the amount that an informed buyer would pay for a property. House prices were soaring then, and people were pissed at their tax bills.

Seeds of the hard math haunting us today were planted seven years later by Bill Sizemore, an anti-taxer who fostered Measure 47, later modified by Measure 50. Both took aim at assessed values, the dollar value of properties subject to tax. Measure 50 lowered assessed values on Oregon properties to 90% of the 1995–96 real market value and made it law that the assessed value could rise just 3% a year. Taxes, Measure 50 said, would be paid on either the real market value or a new “maximum assessed value,” whichever was lower.

Everything was pretty straightforward as long as Oregon property values kept rising. During the boom years, real market values soared, dragging assessed values up by 3% a year. People generally paid taxes on the assessed value, which was lower. Then, the COVID-19 pandemic hit and market values for downtown office buildings tumbled.

Taxwise, it didn’t matter, at least at first. Real market values, which had run up like hares, stayed above assessed values, which had followed like tortoises. As long as that was the case, the basis for property tax bills didn’t change.

Now, though, real market values for office buildings are plunging below assessed values, making them the driver of tax collections and “compressing” them.

Unless you’re a tax expert, understanding compression can seem like trying to hear the sound of one hand clapping. Really, it’s the clatter of Measures 5 and 50 crashing into each other like drunken bicyclists after a beer festival in Waterfront Park. The best way to understand it is probably by example, and there is no better example than Big Pink.

The real market value of Big Pink peaked in 2019 at $456 million, according to county records. That year, though, its maximum assessed value was just $168 million because that value could only rise 3% a year, per Measure 50, while real market value could go through the roof. That meant Big Pink’s owners only paid tax on the assessed value of $168 million. Their bill was $4.3 million.

Big Pink’s real market value plunged during the pandemic, then collapsed this year, when a car dealer named Jeff Swickard bought the place at the low, low price of $45 million.

The sales price of a building doesn’t automatically become its real market value. The assessor could determine that the buyer got a crazy deal because the seller had a gambling debt to pay off, or that the buyer overpaid because there is black mold everywhere.

In this case, Vaughn the county assessor agreed that the building was worth $45 million, far below the $143 million maximum assessed value just a year earlier, in 2024. Vaughn had been lowering the assessed value since 2022, when it became clear that work from home was going to be a thing and that Portland’s downtown would keep struggling, but $45 million was a shock.

“That’s pretty close to the land value,” Vaughn told the City Council.

Here’s where Measure 5 went to work (and bear with us). Recall that Measure 5’s caps apply to real market value. But because properties are taxed on their assessed value, which was kept low by Measure 50, real market values rarely mattered downtown. Taxes on assessed value were still low, relatively speaking, based on market value.

Big Pink stands in a part of Multnomah County with lots of overlapping tax levies, including three that pay for Portland Public Schools, one that funds the Oregon Historical Society, and another for the Port of Portland. Bond levies, which are exempt from Measure 5’s $15-per-$1,000 cap, also add to Big Pink’s bill.

Based on assessed value, Big Pink’s owners have paid about $27 per $1,000 of value over the years. But based on the much higher real market value, all those taxes didn’t hit Measure 5’s $15-per-thousand limit. Now that real market value is below those old assessed values, Big Pink’s tax load must be compressed to $15 per $1,000. PPS, the city, the port, Metro and others must give up some of what they would have collected.

Without Measure 5, Swickard would have to pay $1.2 million, based on the new assessed value. The Measure 5 cap reduces his tax bill to $860,297. Together, Measures 5 and 50 worked in tandem to lop about $350,000 off of Big Pink’s tax bill.

And that’s just one property. Attorneys for property owners (there are two who handle almost all the cases) are piling into tax court to win relief for their clients. Unless downtown Portland recovers soon, they are likely to chalk up some big victories.

For his part, Swickard says Big Pink could spark a downtown revival. “Property tax basis might be lower for now,” he tells WW, “but the real opportunity lies in rebuilding value—in our buildings, our communities, and our confidence. With the right leadership and economic approach, Portland can once again be one of the most dynamic urban centers in the country.”

Fortunately for Portland, taxes on residential real estate account for about 60% of property tax collections, and valuations there have been “resilient,” Vaughn told councilors. If those begin to fall, refunds to the owners of office towers will sting all the more.