Back in the day, Portland was the economic growth engine of the greater metro area. Now, it lags compared with its suburbs, especially Clark County, Wash.

That’s the latest word from Multnomah County economist Jeff Renfro, who briefed the County Board of Commissioners on budget matters today. That doughnut shape, with slumping Multnomah County as the hole in the middle, is strange, Renfro said.

“Metro areas tend to go up and down together,” Renfro said. “To have one county in a metro area that’s performing pretty well and then one that’s really lagging is unusual.”

Federal figures show that the Portland-Vancouver-Hillsboro metropolitan area suffered the biggest employment losses of any large metro in August. Unemployment rose to 5.3% from 4.3%, according to the U.S. Department of Labor. Clark County, meantime, added 2,200 nonfarm jobs in August compared with the same month in 2024.

Asked by Commissioner Julia Brim-Edwards about Portland’s slump, Renfro cited a lack of confidence among investors as one factor. For a second year, Portland placed 80th out of 81 cities among investors and developers considering real estate investments, according to an annual study by the Urban Land Institute, as reported by The Oregonian this week. Only Hartford, Conn., placed lower in overall real estate prospects.

“At some point, you just get below a level on that list and it’s just that institutional investors aren’t interested,” Renfro said. “I’m not sure there’s a substantive difference between 80 and 70 in some cases, but it just means we’re below the level where institutional investors are really interested.”

Because of Portland’s slump, Multnomah County will likely start the 2027 fiscal year, which begins July 1, 2026, with a $10.5 million deficit in its general fund, Renfro said. Revenue is projected to be $789.1 million, while expenses will total $799.6 million.

The general fund is the pot of money that isn’t earmarked by law for specific uses, like Preschool for All, so commissioners have discretion over how to spend it.

Renfro had expected the county to start 2027 without a deficit or surplus, but three factors conspired to whittle revenue: lower assessed property values; tax compression caused by Measures 5 and 50; and slower growth in the county’s business income tax.

Inflation will drive up expenses, meantime. Renfro had expected cost of living adjustments of 2.75% for county employees. Now, COLA is likely to be 3.3%, in large part because President Donald Trump’s tariffs have driven up prices for goods.

“The impact of tariffs is starting to show up in the data,” Renfro said.

Property taxes provide about $64% of general fund revenue in Multhomah County. The business income tax provides about 26%, and car rental taxes bring in 6%.

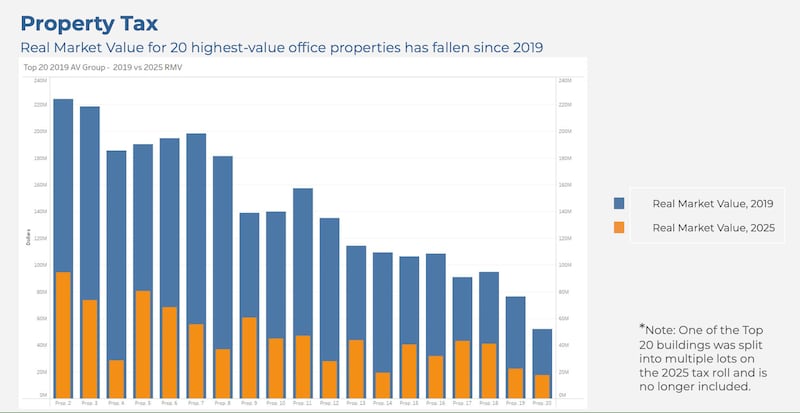

The real market value for the 20 most valuable office buildings in Portland have all fallen since 2019, the year before COVID-19 struck Oregon and protests over the murder of George Floyd turned into riots that prompted downtown landlords to board up windows. The declines are leading to lower tax collections on commercial real estate.

Business income tax collections are running ahead of estimates in the current fiscal year “almost exclusively due to extremely large payment by one company,” Renfro said.

The tax is levied on all businesses that operate in Multnomah County, not just the ones based here. In a typical year, about 45,000 businesses pay it, Renfro said. Usually, about half of all BIT revenue comes from just 300 companies.