This story was produced by the Oregon Journalism Project, a nonprofit newsroom covering the state.

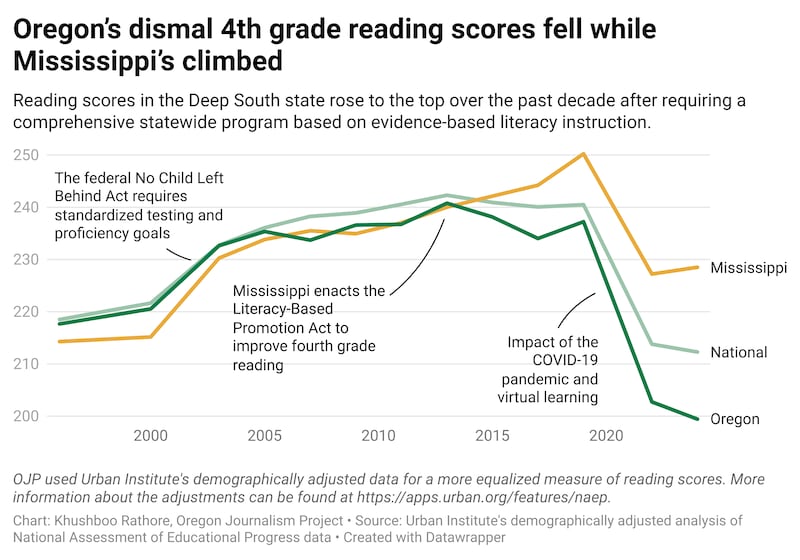

Earlier this year, the National Assessment of Educational Progress released its annual report card, including reading scores for fourth graders across the country.

Reading scores at fourth grade are considered a vital bellwether for a student’s educational progress.

Adjusted for demographics, Oregon landed 50th—at the very bottom. Mississippi, a state some Oregonians like to deride as backward, scored at the very top.

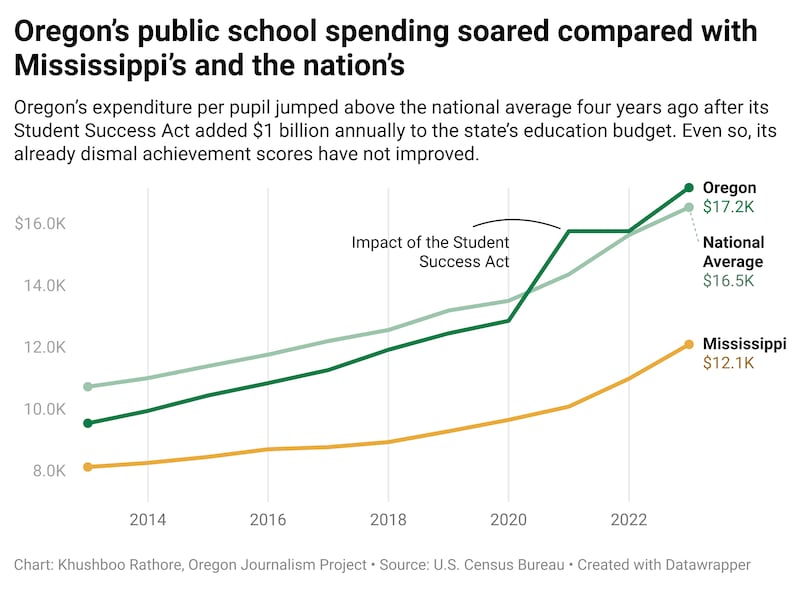

Mississippi is a state burdened by deep poverty, tightfisted public spending, and a punishing legacy of segregation. It spends $13,461 per student a year, $6,000 less than Oregon. And yet, test scores show, students across the board in Mississippi are learning to read in ways that Oregon could only hope for.

The details are dismal: 48% of Oregon fourth graders are below basic proficiency in reading—a deficit that experts associate with failure to graduate, poverty, and increased likelihood of going to prison.

Oregon is in an education crisis, one that parents and students may not recognize because they have positive feelings about their local teachers and classmates. The crisis is also one that leaders in Oregon seem incapable of addressing, despite raising taxes in 2019 that added more than $1 billion a year to the state’s education budget.

This matters because Oregon is failing far too many of the 545,000 K–12 students whose success in life will depend heavily on getting a sound education. K–12 education is the single largest line item in the state’s general fund budget, and it also receives $5.6 billion in local property taxes. But achievement scores demonstrate taxpayer dollars are not being well spent.

The failure threatens Oregon’s shaky economy as well. Schools train tomorrow’s workforce and serve as a decision point for people and employers considering relocating or staying here.

“Every child’s success matters more than ever—it isn’t optional,” says John Tapogna, senior policy adviser at ECOnorthwest. “We owe them the skills and support to build a fulfilling life because their potential is worth it, and our future depends on it.”

Lisa Lyon, co-founder and interim president of the nonprofit Decoding Dyslexia Oregon, calls for urgency. “Oregonians need to care about this crisis today because improving reading proficiency scores and other outputs requires systemic changes that need to happen now if we are to see improvement in a decade.” Meanwhile, she adds, “there needs to be more accountability tied to the distribution of funds.”

There are many reasons Oregon schools are failing, and the Oregon Journalism Project will examine them in the coming months. But first, it’s useful to take a good look at Mississippi’s reading turnaround—built on what’s now called “the science of reading,” strong leadership, and a consistent approach across all districts—to see if it holds lessons for Oregon.

A Billionaire With A Plan

Mississippi’s reading recovery had its genesis in the early 1950s, when Jim Barksdale, the son of a Jackson banker, was falling behind in second grade.

“I couldn’t read,” he would later explain. So his parents hired a reading tutor who taught him how to sound out words, mastering the rules of phonics. Soon enough, Barksdale got back on track and thrived in school, and earned a business degree from the University of Mississippi in 1965.

Barksdale went on to co-found the pioneering internet browser company Netscape, and in 1999 cashed out his Netscape stock for $700 million. He and his wife decided to give away most of their fortune. They allocated $100 million to improving the way Mississippi children learned to read—and to change their home state’s chronically abysmal test results.

“You know what it’s like to be dead last in every race for something like 40 years?” Barksdale would tell reporters. He was sick of hearing Arkansas, ranked 49th, say, “Well, thank God for Mississippi.”

So Barksdale set up a nonprofit in 2000, the Barksdale Reading Institute, and hired some of the best educators and experts to come up with a plan.

By then, there had been a sea change in thinking about reading instruction after advances in brain imaging and neuroscience showed how the brain functioned as children learned to read. The seminal National Reading Panel concluded in 2020 after synthesizing 40 years of research that “teaching phonemic awareness to children significantly improves their reading more than instruction that lacks any attention to” phonemic awareness. The research supported explicit, direct instruction in phonemic awareness and phonics, advancing to vocabulary building, fluency and comprehension. This and other research-backed methods are commonly called the science of reading.

Kelly Butler, a former Connecticut high school teacher with a degree in special ed, joined the Barksdale Reading Institute in 2003 and rose to be its CEO.

In college, she hadn’t been trained how to use phonics to teach early readers. At the time, colleges taught a reading philosophy known as whole language or “balanced literacy”—methods now thoroughly discredited but still used in some Oregon schools today.

The Barksdale team adopted science-validated reading methods, Butler said, creating instructional materials and hiring reading tutors and coaches who could train other teachers in phonics-based instruction. They tested and perfected their methods at 15 of the worst-performing grade schools in Mississippi.

The state’s reading turnaround was later dubbed “the Mississippi Miracle,” but Butler and others downplay the hype, saying it wasn’t a miracle at all because they knew the science of reading worked—it just had to be applied, tracked and sustained by trained teachers and coaches who used an approved curriculum.

“Which is why I call it the Mississippi Marathon,” she tells OJP. “Between 2000 and 2013, the Reading Institute was really at work in the trenches trying to design a structured literacy model.”

In 2013, Mississippi lawmakers passed sweeping legislation, the Literacy-Based Promotion Act, that funded the Barksdale model statewide, from early screening to training thousands of teachers and literacy coaches who fanned out across the state’s 1,040 public schools.

The controversial part of the 2013 law was the requirement that students be held back if they did not meet reading standards by the end of third grade.

“Our emphasis in implementing this reading law was to retrain teachers rather than focus on retaining kids,” Butler says. “Because this is really an adult problem, it’s not a kid problem.”

Some critics have questioned the validity of Mississippi’s fourth grade reading gains by noting that when that cohort reaches eighth grade, their scores have regressed, or that holding back struggling third grade readers boosts the fourth grade NAEP scores.

Andrew Ho, a testing expert at Harvard University and previously a member of the board that oversees NAEP, said he reflexively questions big test score gains. But in Mississippi’s case, he told Chalkbeat, “I don’t see any smoking guns or red flags that make me say that they’re gaming NAEP.”

Still, the changes weren’t always welcomed, certainly by teachers used to years of local control and taught that phonics instruction was “drill and kill” that took the joy out of reading.

“We had one school picket us one day and said, ‘Go home, Barksdale,’” Butler remembers.

Flawed Training, Tight Local Control

For many years, Oregon parents and K–12 advocates focused their energy on increasing school funding, not accountability. They’d descend on Salem in swarms, pleading with lawmakers to increase the budget.

Many states fund schools primarily with local property taxes. Oregon did, too, but voters changed that in 1990 with Measure 5, and in 1997 with Measure 50, which capped the growth of property taxes. Today, two-thirds of Oregon K–12 funding comes from the Legislature.

In 2019, lawmakers brought Oregon’s public education spending above the national average with the Student Success Act, which added $1 billion a year through a corporate activities tax. But more money didn’t lift reading scores. In fact, the scores continued to decline.

Some experts raised concerns about the flaws in Oregon’s teaching methods. University of Oregon education professor emeritus Doug Carnine, who helped build the science of reading movement, and others had done research in the 1990s that established that the best way to teach children to read was through phonics and by measuring progress.

But to Carnine’s frustration, many of his colleagues at UO and other Oregon teaching programs refused to follow the science, citing academic freedom as an explanation.

“Do you think a doctor could do lobotomies for mental health under the name of academic freedom? No. Academic freedom does not trump your code of ethics for your professional behavior,” Carnine says. “It’s ridiculous, just absolutely preposterous.”

Local Control, Flawed Curriculum

Could the Mississippi model—firm department leadership; state-selected, science-based curriculum; performance tracking and quality control—work in Oregon?

It crashes up against a basic tenet of public education, especially in Oregon: local control. Oregon has 197 school districts governed by boards made up essentially of volunteers elected by their communities but often with little knowledge of the best curriculum for their schools or the latest research.

Sarah Pope, executive director of the education nonprofit Stand for Children Oregon, hopes the state can benefit from Mississippi’s example. But Pope also knows that the Oregon Department of Education dictating changes to local school districts would require a fundamental change in the state’s political landscape.

For instance, while ODE recommends that districts use early reading materials from an approved list based on the science of reading, local districts are not mandated to do so, and they can use any materials their school board approves.

Pope, Lyon and others maintain that some districts still use subpar materials. ODE itself is not certain whether instruction based on the science of reading is taking place in all districts’ classrooms.

Pope, for example, says that her children’s school district, Beaverton, “up until last year was using a reading curriculum that was proven not to work.”

As chief of staff for the Oregon Department of Education from 2012 to 2015, Pope said she learned ODE had authority that it did not use.

“ODE could have said [to my district], ‘You can’t adopt something that is proven not to work.’ But instead they say, ‘OK, you don’t want to adopt what we recommended, but as long as you go through a local process, you can adopt whatever you want.’”

Over the weekend, OJP sent questions to Gov. Tina Kotek through her office to ask what she felt about the state’s bottom ranking in reading. Unlike in most states, Oregon’s governor is the state’s top education official. As of deadline, Kotek did not reply to questions.

Why are Oregon’s schools failing? Who is responsible for the failures? And, most importantly, how do we dig ourselves out of this? If you are a student, parent, taxpayer, teacher or former teacher, school administrator or policymaker with ideas on how to answer these questions, we want to hear from you. Please share your thoughts and how to reach you by going here.