Five years after her father’s death, Agathe arrives at her childhood home in Périgueux, France, for the first time in 15 years. It is time to confront a household of items, and both her relationship with her sister and to the place she once called home. There is the bunk bed, looking too rickety to hold the bodies of two adult women; there are the crystal vases, too formal for the sisters’ reunion. And then there is the unfamiliar, which evokes a sadness in Agathe that she cannot express aloud: the birdcage in the living room full of aging cheese; the bamboo plates; a fireplace full of books. And Véra herself.

Early in the process of sorting through dishes and bric-a-brac and the clothing, Agathe relives snapshots of her childhood: the tension of their parents’ relationship; the pain of their mother’s departure; and her own departure for New York at age 15, leaving behind 12-year-old Véra.

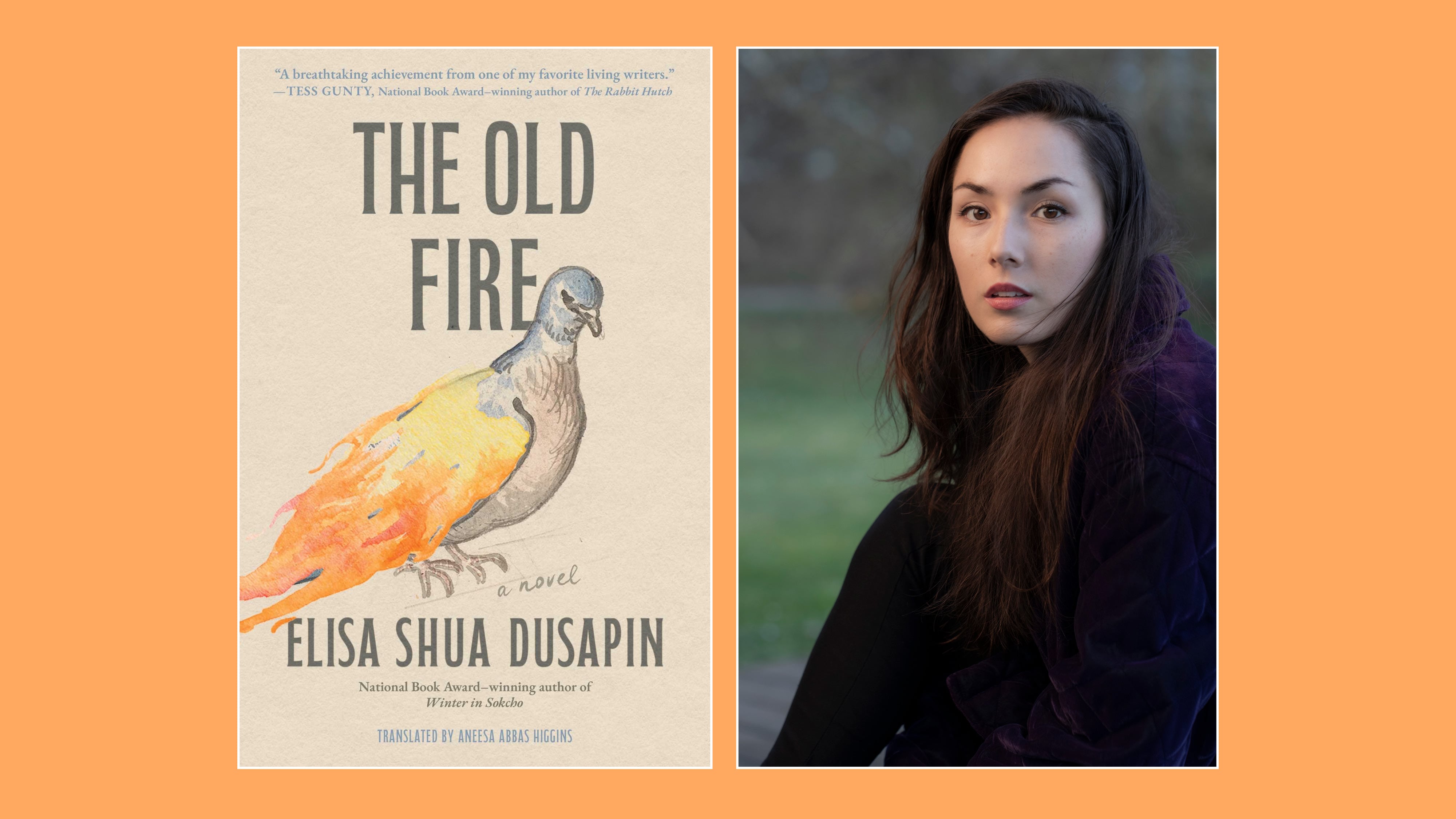

The fourth book by 33-year-old writer Elisa Shua Dusapin, The Old Fire (Simon & Schuster/Summit Books, 192 pages, $27) is a short novel that packs more into its pages than seems possible. Dusapin’s storytelling and exploration of complicated female relationships evokes Elena Ferrante’s Neapolitan novels and Michael Ondaatje’s Divisadero.

I was immediately drawn to the narrator’s voice; to what she says aloud and what she keeps secret. The sisters’ unfamiliarity with each other is at times painful to watch.

Communication is a key theme in Fire: Véra has not spoken aloud since she was 6 years old, so the sisters communicate via text messages and notes, further increasing the tension around the conversations they both must face. What to get rid of? Why didn’t Agathe ever come home? What did Véra face in staying behind?

Agathe, now a successful screenwriter in New York, finds herself out of place when she returns to the French countryside. At first, she is defensive: There is so much about her home and her country of origin that she no longer relates to, be they customs she lost over the years or ones she never learned as an expatriate coming of age in the States. She observes her sister with intent curiosity, and resentment, too—though she may not be able to name it as such.

But both sisters have something to be resentful for. Agathe is resentful of her disconnect from her culture, her family; and Véra resents Agathe’s leaving. One such moment is demonstrated in a terribly sad flashback that takes place shortly after the girls’ mother leaves. Véra has battled her abandonment by acting out; Agathe takes her 9-year-old sister’s mittened hands in hers and promises: “I’ll always be there for you.”

It was a promise she did not intend to break, and one she has limited time to mend, if she can.

Since the girls do not have the means to repair the old stone home, they have signed a deal with a company who in nine days will demolish it and turn the property into a campsite. Originally, the home was part of the neighboring château, Le Pigeon Froid, which is still owned by the family’s son, Octave, a kind character who acts as a rehoming space to help offer Agathe a sense of belonging and connection. Octave hopes to use some of the stones from the soon-to-be-demolished property to rebuild the château’s pigeonnier, which burned down years ago, with the pigeons inside it (thus the book’s title, originally Le Vieil Incendie). Brace yourself for a heartbreaking scene but fear not; like each point of sorrow, Dusapin handles the storytelling with much wisdom and reserve.

The Swiss-Korean author often writes on themes around mixed identities and multiculturalism. Dusapin’s 2016 debut novel, Winter in Sokcho, winner of the Prix Régine-Deforges and the National Book Award for translated literature (alongside the same translator, Aneesa Abbas Higgins), explored loneliness and multiculturalism through the story of a French cartoonist and a Korean woman who works at a guest house. In Fire, Dusapin explores the particular experience of feeling like an expatriate in your own country; the ways memories can elude and haunt; and reconciling one’s own place in their family history. In particular, it answers that painful question: Can we ever really go home again? In short, no, we can’t. Not truly. Dusapin tackles the complexities of this story with writing so beautiful as rendered into English by Aneesa Abbas Higgins—wise in its observations, simple in its delicacy—it makes me cry.

BUY IT: The Old Fire by Elisa Shua Dusapin is available Jan. 13.