Between 2016 and 2018, the city of Portland installed eight fixed speed cameras along its deadliest streets. The cameras, which look like a flock of WALL-E robots perched on a pole, can detect a speeding car, take a photo of the vehicle and its driver, and issue a speeding ticket.

Biannual reports by the city to the Oregon Legislature about the efficacy of such cameras show they are perhaps the most successful tool the city has for reducing vehicle speeds, which directly correlates to decreasing traffic accidents and deaths.

The camera installations happened right around the same time as the launch of Vision Zero, a citywide campaign to eliminate traffic deaths by 2025. That the campaign has failed to accomplish that is obvious—in fact, Portland, like many of its peer cities, has more traffic deaths annually than when it started the program nine years ago, despite spending $330 million on safety improvements along high-crash streets since 2017.

Yet during that time, city officials have installed only seven more of the fixed speed cameras. And when a committee of the Portland City Council passed a resolution in May that “reaffirms” the city’s commitment to Vision Zero, the efficacy of the traffic cameras—and their slow rollout—went unmentioned.

To be sure, the city is set to expand the program by nine cameras within the next year—a plan that avoided the budget ax this past month. And the city hopes to increase the total number of automated cameras to 60 by 2028. (PBOT currently has 31 automated cameras in operation, which include the fixed speed cameras but also dual red-light and speed cameras, and two mobile van cameras. The 60 total would include dual and fixed speed cameras.)

But after a searing audit of the city’s Vision Zero program last fall, in which the city auditor said the city was largely failing to track which of its safety projects actually succeeded in reducing traffic crashes, some observers are asking why one of the few programs with proven results isn’t being more aggressively expanded.

City Councilor Steve Novick says installing more fixed speed cameras is an obvious choice.

“New York City has 3,000 of these things. Based on road miles, I think we should have 1,000,” Novick says. To go from 30 to 60 cameras in the next three years, he says, “seems like a glacial pace.”

Last November, Portland City Auditor Simone Rede chastised the Portland Bureau of Transportation for not regularly tracking which of its efforts to decrease traffic accidents were actually working.

The bureau should “systematically evaluate completed safety projects to determine which get the desired outcomes and where Vision Zero efforts are most needed,” the auditor found. Basically, the auditor said, PBOT wasn’t regularly tracking which projects actually worked to decrease speeds, accidents and fatalities—the very goal it’s been chasing for nearly a decade.

“Without systemic evaluation of safety outcomes, the bureau is missing the opportunity to create more alignment between the work they do on safety projects and the overall goal of Vision Zero,” the audit read. “A more systematic approach would allow trends to be identified and analyzed to better understand the outcomes of completed projects, and which may need to be altered or dropped.” (The audit wasn’t all bad; it lauded the bureau for its left-turn traffic calming installations, for lowering speed limits in residential areas, and for delaying green lights to allow pedestrians to enter the crosswalk before cars turn into them. In its response to the audit, PBOT stated it is “consistently completing evaluations for significant safety projects” and “began using an updated consistent methodology for High Crash Network projects in 2023.”)

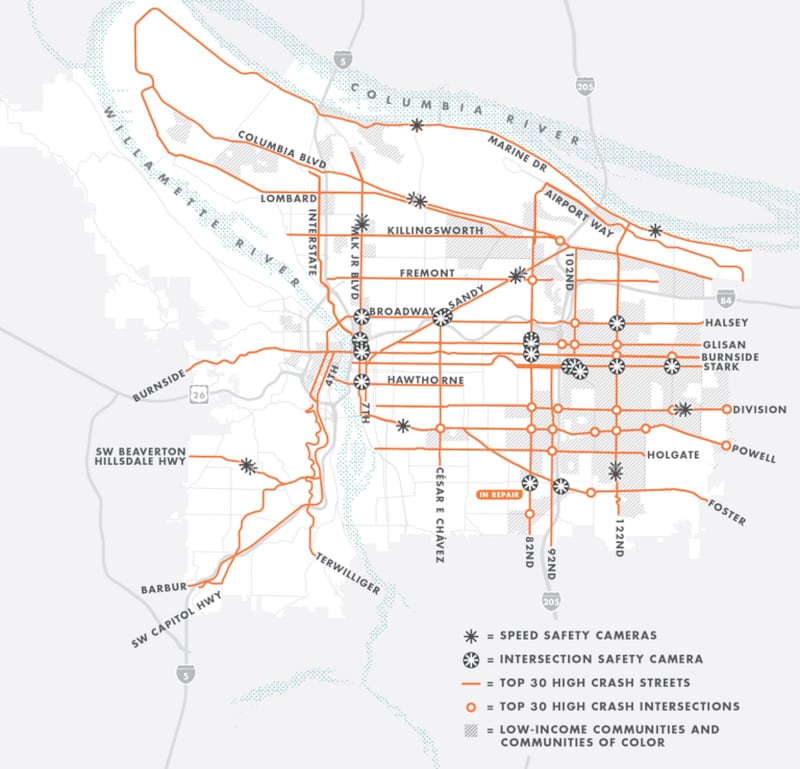

The city auditor’s criticism was especially cutting because one of Portland’s strategies to lower speeds has undeniably been successful: its 15 fixed speed cameras along eight of the city’s most deadly streets. Half of the cameras are installed along streets in Northeast Portland. Another handful keep watch on high-traffic streets that run east to west. Two cameras overlook Southwest Beaverton Hillsdale Highway between Portland and its western suburbs.

The city installed the first eight cameras between 2016 and 2018 after obtaining permission from the state Legislature. It planned to install another four in 2021, but didn’t put up the next batch—seven total—until 2024 due to procurement hitches.

By PBOT’s own telling, speed is the No. 1 factor in traffic deaths. The bureau says 42% of the city’s traffic deaths between 2017 and 2021 “were because of speed.” And 59% of deadly crashes, the bureau says, occur just on the 8% of city streets that have speed limits of 35 mph or higher.

And the city’s biannual reports to the Legislature about the efficacy of its fixed cameras show undeniable results: The cameras reduced speeding and crashes.

“The number of drivers speeding decreased significantly at every location where a speed safety camera was installed,” PBOT reported to the Legislature.

The bureau’s data shows speeds along high-crash corridors with fixed speed cameras decreased 59%, according to a study in 2024. Vehicles traveling 11 mph or more over the speed limit decreased by 88%, the report shows. (The report collected data only from cameras that had been in place for at least five years, so not all 15 cameras were included in the snapshot.)

The report noted: “Fatal and serious injury crashes increased by 41% citywide between the 2012-2015 and 2019-2022 time periods. Speed camera corridors saw a much lower increase in fatal and serious injury crashes by only 9%.”

The November audit urged the city to install the promised fixed speed cameras “to further support street safety,” noting that the “bureau fell short with most cameras not placed in the planned time frame.”

So why hasn’t the city installed more speed cameras and done so faster? PBOT spokesman Dylan Rivera says procurement hitches delayed the placement of the eight cameras installed last year. And because police officers are currently the ones to review all citations, mostly on overtime shifts, the bureau is limited by police availability. They’re also hamstrung by capacity at the Multnomah County Circuit Court, which adjudicates the citations.

Another reason: concerns about who gets cited.

Sarah Iannarone, executive director of the Street Trust and a longtime transportation advocate, supports automated cameras but says she’s keenly aware that they could disproportionately penalize low-income drivers.

“The high-crash corridors also have higher concentrations of people living on low incomes,” Iannarone said. “So by concentrating the cameras there, while you may be reducing speeds, you might be having a negative impact on low-income households.” (On a brighter note, Iannarone adds that the cameras may “mitigate racial profiling and bias” by reducing “biased policing interactions.”)

The Street Trust supported a 2022 bill that gave the city permission to have nonsworn employees review camera citations, not just sworn police officers working overtime.

The bill passed, and PBOT says with its planned expansion in the coming years, it’s looking to hire three people who can review citations to alleviate the burden on police staffing and increase the number of tickets the city can process.

Ianarrone says the cameras should be “safety driven, not revenue driven” because they could create “a perverse incentive for governments to use those in regressive ways.”

The Vision Zero Network said as much in a Feb. 3 article on its website, writing that “cameras should not be the automatic go-to solution for areas that warrant more lasting and equitable solutions” and that “improving street design should be the first line of action in creating safe environments, rather than enforcement.”

Iannarone says another option is to ask communities the tough question.

“One of the ways we could address it: Go to the community and say, it’s a proven solution. These unsafe streets are a threat to you. So we’ve seen that these cameras work. What would equitable enforcement look like to you?”

On May 19, led by Council Vice President Tiffany Koyama Lane, the City Council’s Transportation Committee passed a resolution that “reaffirmed” the city’s commitment to Vision Zero. Among the clauses: “change the design of streets to reduce speeds and protect people.”

Koyama Lane’s resolution directed the city to convene a new Vision Zero Task Force to “support the goal of zero traffic deaths and evaluate and report to council on advancement of those goals annually.” Traffic safety cameras went unmentioned in the council’s discussions around Vision Zero, though Koyama Lane says she’s in full support of them.

“In the first six months of our new City Council, there haven’t been a lot of opportunities to work specifically...on projects such as fixed speed traffic cameras,” Koyama Lane says. “I have noticed many more installations and fully support them as a cost-effective intervention that does indeed reduce crashes and the resulting injuries.”