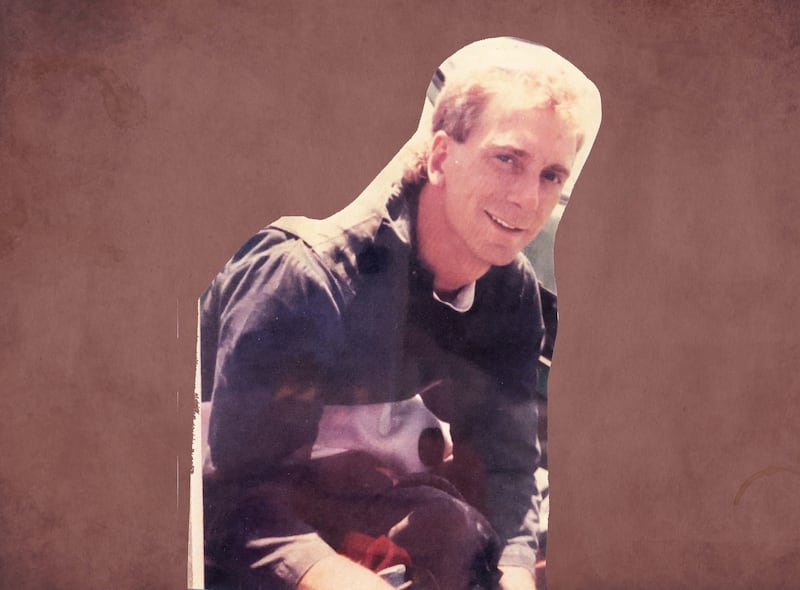

Kenny Fandrich is dead, just as he predicted.

The 56-year-old from Oregon City had said so for years—to pals, cops, lawyers and, of course, his wife, Tanya. He knew it was just a matter of time.

And while he didn’t know when or how, Fandrich was sure he knew who. He claimed his death would come at the hands of a local veterinarian, Steven Milner.

Milner had been a fixture in Oregon City for more than 20 years. He ran a successful veterinary practice that treated the family pets of a who’s who of the 38,000 residents of this quiet suburb on the banks of the Willamette River a dozen miles south of Portland.

Noted for his empathy, Milner kept a box of Kleenex in his office and was given to weeping, alongside grieving owners, after putting down their cats and dogs. Afterward, he would send sympathy cards. The idea that this gentle country vet could pose a threat to anybody seemed absurd.

Kenny Fandrich claimed he was being stalked by the nicest man in town.

“He’s a psychopath,” Fandrich told Hillsboro police more than a year ago, according to police records. “He told me he’s going to chop me into a million pieces—and make sure it takes days to do it.”

Last January, someone did end Fandrich’s life in savage fashion in a parking garage on the Ronler Acres campus of Intel Corp. in Hillsboro, where he worked as a pipefitter. Prosecutors have not identified a murder weapon, but a medical examiner’s report says Fandrich, a 6-foot, 195-pound union foreman, was killed by “blunt compressive trauma to the neck.” It was applied with such force that it severed his spine.

Five days later, Steven Milner, 56, was charged with second-degree murder in Washington County Circuit Court and pleaded not guilty. A trial date has yet to be set. If convicted, he faces life in prison.

“How the hell could he have done this?” says Nancy Broshot, who entrusted several dogs and cats to Milner and remembers him as a caring man with a wry sense of humor. “It’s like Jekyll and Hyde.”

The picture that emerges from voluminous evidence collected by prosecutors is one of an outwardly model citizen who became so obsessed with a former employee that it led him to kill her husband. But the case, easily dismissed as an oddity, raises important questions. Prosecutions of stalking in Oregon have surged in recent years, from 3,000 in 2018 to more than 4,500 last year. So have murders, of which there were 136 last year. Studies have shown that the two crimes are often linked.

So, why then, with so many obvious signs that Milner had gone off the rails, did no one intervene for so long? Stalking is difficult to prosecute. Kenny Fandrich’s story suggests the consequences.

According to many people WW interviewed, Milner was a phenomenal vet.

“Absolutely amazing,” says Darlyn Robinson. She took more than a half-dozen dogs to Milner over the years, from a giant schnauzer to a Rottweiler named Elvis. She remembers one Fourth of July when Milner rushed back to his office to get a sedative for her dog, who was spooked by fireworks.

Cheryl Choquette raved about his care. “I referred all my family and friends. Everybody liked him,” she says.

A number of people recalled Milner’s kindness during the final minutes of their pets’ lives.

After Broshot’s border collie, Lady, was put down following a grand mal seizure, Milner sent her a sympathy card and contributed to his alma mater, Oregon State University, in her dog’s memory.

“I never saw that before,” Broshot recalls. “It was a nice touch.”

Broshot had taken her pets to Milner ever since he first moved to Oregon City right out of veterinary school and he got his start scrubbing cages at a tiny clinic in the suburb’s quaint downtown. And when he set out on his own, building his own brand-new clinic up the hill, she—and many others—followed him.

By the time Milner retired, in 2020, he had one of the busiest clinics in town, and five doctors working under him.

“He’s the best boss I’ve ever had,” recalls Brandi Rieg, one of his former receptionists. “Professional, kind and generous.”

Milner, who awaits trial in Washington County Jail and declined to speak to WW, grew up near Tillamook before attending OSU, where he joined a fraternity and graduated with a doctorate in veterinary medicine in 1993. According to some people WW interviewed, Milner was a talker.

“I’ve always liked being around people,” he told his daughter in an oral history published online. “But work was a bit of a drudge.”

While Milner had a mostly clean medical record, he was investigated in 1996 by the Oregon Veterinary Medical Examining Board for “unprofessional or dishonorable conduct” after he euthanized two dogs without their owner’s consent.

The incident, for which the board dropped its investigation a short time later, did nothing to slow his career. And Milner, who had two children from his first marriage, was more than a vet; he was actively involved in civic affairs. He sponsored fundraisers and charity runs. He hosted a hygiene station for the homeless and collected bottles and cans from clients, donating the redemption proceeds to charity animal care.

Milner did flash a temper in 2019, when he exceeded the allowed size of bottle deposits and BottleDrop, the redemption program operated by the Oregon Beverage Recycling Cooperative, canceled his account. Milner exploded; he went on KOIN-TV to protest. He didn’t mention that he’d shoved one BottleDrop employee and doxxed another by posting her telephone number online, says OBRC president and CEO Jules Bailey.

“He started encouraging all of his supporters to call her and harass her, and then threatened to come find her,” Bailey says. “I’m not a psychologist, but he’s clearly a sociopath.”

The following year, Milner retired and sold the clinic to a national chain. He was wealthy, divorced and an avid hunter—he could easily have easily spent the rest of his life stalking big game.

Kenny and Tanya Fandrich married in 1993 after meeting in Dutch Harbor, a major fishing port in Alaska’s Aleutian Islands. Kenny was a scuba diver and worked as a welder on commercial fishing boats. Tanya worked at a bank. After being introduced by a mutual friend, the two went out for ice cream in Tanya’s hometown, Anchorage, nearly 800 miles away.

“He was as crazy about animals as I am,” recalls Tanya, now a soft-spoken 55-year-old brunette whose blue eyes fill with tears at the memory of her lost husband.

Kenny grew up in Estacada, and when he returned to Oregon in 1996 to start a business with his father, Tanya came too. They built a house in the countryside northeast of Oregon City and filled it with pets: six dogs, two cats, a pair of goats—and, briefly, a baby raccoon that liked to snuggle against Kenny’s head.

In 2000, Tanya took a job at the brand-new Milner Veterinary Hospital. She was one of its first employees and, for 19 years, her relationship with Milner, she tells WW, was professional—although sometimes not.

Milner divorced twice and, according to Tanya, would brag in the office about making his ex-wives miserable during the legal proceedings.

Tanya, too, was having problems at home. She and Kenny drank heavily, and Kenny was not always faithful to her, Tanya says. He was often out of town, living at job sites in an RV.

Tanya and Milner became close. And, in 2017, their friendship became something more. “I was lonely, and someone was paying attention to me,” Tanya explains.

It lasted five months, Tanya says, before Kenny found out. Tanya had gone home with Milner after a co-worker’s wedding and, when she returned to her home, Kenny was gone.

He soon forgave her, she says. “It was wrong, and I will regret it for the rest of my life,” Tanya tells WW.

The stalking began soon after, Tanya says. The first incident documented by Kenny in legal filings occurred in late 2017, when he received an anonymous, threatening letter. “I should do everyone a favor and go back to drinking myself into my own demise,” Kenny recalled it saying.

Tanya became certain Milner was behind the letter, and contemplated quitting. But, having worked at the clinic for nearly two decades, she couldn’t imagine leaving.

For the next four years, on at least a dozen occasions, Tanya and Kenny received threatening letters and phone calls, and endured even more serious invasions of their privacy.

In September 2018, Tanya and Kenny drove home to their house, which is surrounded by woods and perched at the top of a winding driveway. There was Milner, in a blue hoodie, lying under Kenny’s Dodge Ram as he affixed a small black box to the truck’s undercarriage. Milner fled and Kenny called 911. The interagency bomb squad that serves Clackamas County examined the device and determined it was a GPS tracker.

In interviews with police, Milner admitted to installing the tracking device but argued he was still having an affair with Tanya and was simply keeping tabs on Kenny. Tanya repeatedly denied this.

Clackamas County Sheriff’s Deputy Zachary Keirsey didn’t believe her. In his report, Keirsey said her “calm” demeanor and “flat affect” during the interview “seemed out of character for someone in her position.” He decided not to pursue charges.

Even Kenny’s friends found his fears somewhat far-fetched, until Kenny installed cameras and they saw security footage of Milner sneaking around the Fandriches’ property. Dan Mejia, who worked with Kenny, said Kenny’s friends, like many people in rural Oregon, had guns. “We can take care of this, Kenny,” Mejia told him.

But Kenny demurred. He was willing to leave it to the cops. “He was blindly faithful to the system,” Mejia says.

On June 8, 2019, Kenny said he found Milner screaming outside his front door, threatening to cut the pipefitter into a thousand pieces.

Kenny was terrified and, in August 2019, applied for a temporary stalking protection order against Milner.

“[Milner] appears to be getting angrier and angrier by the day,” Kenny wrote in his application. A sheriff’s deputy personally served Milner with a copy of the order the next day at his clinic.

Two months later, however, Kenny allowed the order to expire. Milner had threatened to bankrupt the couple with legal fees, and Tanya convinced Kenny it wasn’t worth the risk of antagonizing him, according to later police reports.

That year, Tanya finally quit Milner’s clinic and started a new job at a clinic in another town.

It didn’t stop the stalking. Milner followed her there, too, leaving notes on her car. Once, he showed up at the clinic with a dog and demanded Tanya treat it, she says.

Tanya’s new co-workers noticed Milner hanging around. One says, “I thought he was just some crazy person with too much time on his hands.”

Clackamas County sheriff’s deputies were also dismissive, despite the fact that it’s illegal in Oregon, as in other states, to plant a GPS tracker on a vehicle without the owner’s consent. (Kenny later said he’d been told by a cop that this wasn’t true, according to a police report.)

On Dec. 30, 2020, one of Kenny’s surveillance cameras spotted someone crawling around on their belly in the yard. Tanya called 911, but deputies left without even bothering to write a report.

It happened again one month later, and this time the bomb squad found a tracker under Tanya’s Chevy Volt. It was manufactured by Spytec and available for $18 on Amazon. The county opened an investigation and Deputy Beth Lang gave Milner a call. The veterinarian played coy, Lang said—Tanya had told him to “look for her body in her cistern” if she ever disappeared, he said, implying he’d installed the tracker to protect her.

Lang had severaltheories about the case: Perhaps Milner was overly concerned for Tanya’s safety or Kenny was planting the trackers himself to frame Milner, she told Tanya, according to her police report. No charges were filed.

At that point, Milner seemed to back off.

But the strains in the Fandrich marriage continued, according to Tanya. Kenny liked to drink, a lot, usually out of large McDonald’s cups. Sometimes their fights turned violent. “For the second time in a week, there’s blood all over the house and it’s not hers,” Kenny told a friend, according to text messages later read in court.

In August 2021, Tanya slashed her husband’s ear. Kenny called the police and Tanya was booked in jail for assault.

When she was released, Milner was waiting outside, saying he’d bailed her out. “You’ve gotta be fucking kidding me,” Tanya recalls thinking. “How does he know?”

She and Kenny came to believe he’d installed trail cams on their property—the kind used by hunters to track deer—and was watching their every move.

In his retirement, Milner had more time on his hands. He began following Kenny to work along rural Clackamas County backroads and onto Highway 43. On Aug. 2, 2022, Kenny was so spooked by the Toyota RAV4 tailing him that he called 911.

A Hillsboro police officer pulled Milner over and let him off with a stern warning. But after talking to Kenny and further reviewing prior police reports, the officer determined there was probable cause to arrest the veterinarian for stalking, according to a police report filed two days after the traffic stop. The officer referred the case to the Clackamas County Sheriff’s Office. The sheriff’s office made no arrest and filed it away.

At the recommendation of Hillsboro police, Kenny obtained another stalking protective order. A month later, Tanya was getting her Chevy Volt serviced at Jiffy Lube when a mechanic discovered another GPS tracker. She called the sheriff’s office, which investigated and determined in August that the tracker and six others were registered with Steven Milner’s name, address, phone number and credit card.

Milner was arrested that month and charged with violating the stalking order and unlawful use of a GPS device, both misdemeanors.

He was released from jail pending trial, but he appeared to be taking the charges seriously. By Christmas, the Fandriches hadn’t seen him for months, Tanya says. Kenny was working on getting sober. The couple was contemplating retiring to the coast. “We thought it was finally, finally over,” Tanya says.

For the past decade, Intel has been building a 2.5 million-square-foot fab in the middle of suburban Hillsboro. It’s called D1X. Inside, an army of engineers design the most advanced microchips in the world.

But to build and maintain D1X, Intel also relies on an army of tradesmen— “construction folk,” in Intel parlance. They work in a series of low-slung office complexes on the east side of the Ronler Acres campus, accessible only by a side entrance.

That’s where Kenny Fandrich worked, installing the piping that keeps the heavy machinery cool. And it was there, on a chilly winter afternoon in a parking garage, that he died.

Prosecutors allege Milner painstakingly planned the murder for months. He purchased a pair of beater cars—a blue Buick sedan and a maroon Dodge Caravan—and took them on reconnaissance missions to stake out the facility. He bought a pair of tinted safety glasses at Home Depot for a disguise.

Then, on Jan. 27, Washington County prosecutors say, Milner put his plan in motion.

Early that morning, he drove the Buick to the Intel campus and, face hidden by the glasses and a hard hat, he walked through the five-story garage where Kenny would soon park his car and sprayed security cameras with blue paint.

Milner returned that afternoon, this time in the Caravan, which he backed into a parking space next to Kenny’s Honda Civic, and waited.

Security cameras captured Kenny’s last moments alive. First, pushing through a metal turnstile as he left work. Then, climbing the stairs to the floor of the garage where he was parked. And, finally, approaching his car.

What happened next remains unclear. Images capturing the killing are mostly obscured by paint. The Civic’s headlights flash several times. There’s movement between the minivan and Kenny’s car. A half hour later, the Caravan leaves.

Police discovered Kenny’s body later that night after he failed to return home from work. His body was slouched in the driver’s seat.

It’s still not clear what weapon, if any, was used to break his neck. Mejia, a former Marine, thinks Kenny was ambushed and put in a military chokehold—the “one-second kill.”

Detectives immediately suspected Milner. Police seized his RAV4, which had an onboard GPS that periodically recorded its location. It had stopped at the Oregon City Home Depot, where Milner had purchased the familiar pair of safety glasses. And it stopped at a North Portland homeless encampment and on a shoulder of Interstate 5 where the two beaters were found abandoned.

Most damning of all, Milner’s DNA was found on Kenny’s hands.

The retired veterinarian was arrested five days after the killing—with makeup covering a black eye. “Kenny got a shot off, too,” Mejia says.

Milner’s trial isn’t expected to start for at least another year.

In the bail hearing May 12, his attorneys tried their best to cast doubt on the state’s assertion that the killing was intentional, noting that footage from the moment of Kenny’s death was obscured. “We have no idea what was happening,” said Amanda Thibeault, suggesting the 245-pound verinarian had acted in self-defense. “Fandrich had a history of violence.”

And, they had a backup plan: shift blame to Tanya.

Thibeault argued that Milner and Tanya remained romantically involved. “It’s sick, it’s vile,” Tanya says of the accusation.

Circuit Judge Erik Bucher wasn’t swayed. “It’s a very easy ruling,” he said, denying Milner bail.

Meanwhile, Milner’s case has become a source of fascination around town in Oregon City. The clinic he once owned has scrubbed his name from the sign out front. The pot farm he owns with his uncle asked the Oregon Liquor and Cannabis Commission to remove Milner from its license in May.

Milner’s neighbors think he’s innocent, WW is told. But on a recent visit to his home high in the tree-topped hills of unincorporated Clackamas County, WW was unable to find out why.

Passersby warned a reporter to be careful, that the neighbors are armed and don’t appreciate representatives of the media. Milner’s house is accessible only by a long private road, flanked by “No Trespassing” signs.

Kenny’s friends say the system failed him. So does Tanya. When she showed up at the scene of her husband’s death, a cop was dismissive of Kenny’s efforts to gain protection through the law.

“Stalking orders do nothing more than piss a person off,” Tanya says he snorted. “I was appalled. How can that be justice?”