EUGENE, Ore. — Neon-clad construction workers are scurrying around the Portal, a new 130-unit market-rate apartment building with commanding views of parkland leading the eye to the nearby Willamette River and the distant Cascade Range. They aim to finish work by next month on the second of a planned dozen buildings in a public-private partnership that officials say would transform Eugene’s long-neglected waterfront.

“Eugene needs more affordable housing, more compact housing, and more housing in walkable neighborhoods,” Eugene Mayor Kaarin Knudson says. “Downtown presents a unique opportunity to accomplish all of these goals, and significantly add to the housing diversity that serves our community.”

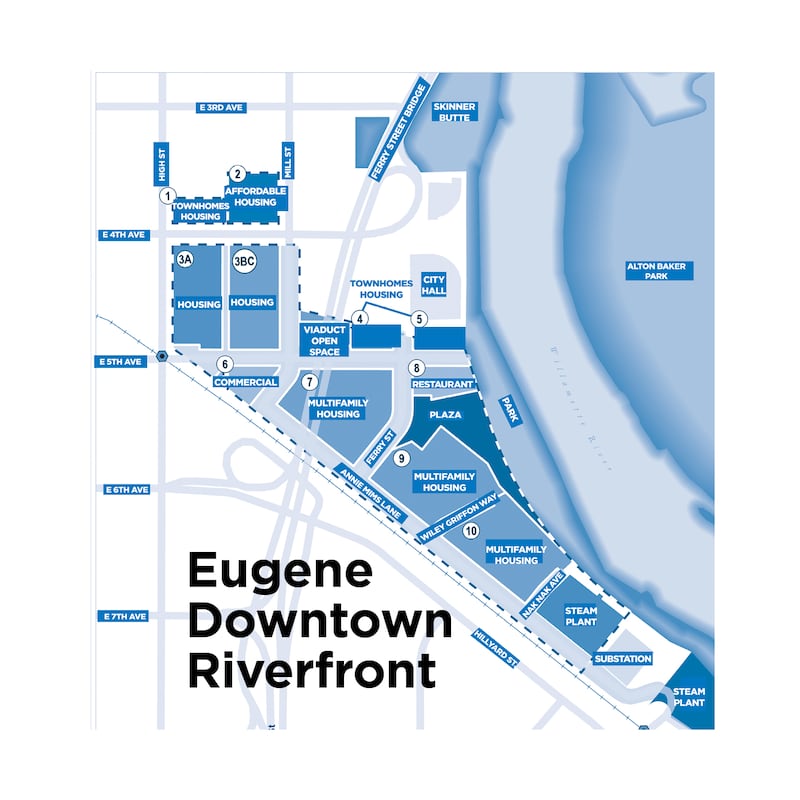

The plan: build up to 1,300 new apartments on eight parcels of land, which would increase the supply of housing in central Eugene by 50%, along with retail and restaurants built around a new waterfront park and plaza.

The Eugene Riverfront development project will connect a historic section of the city’s downtown to the University of Oregon’s campus upstream, a unification 20 years in the making (see map below).

That is, if state officials don’t stall the project before developers break ground on the remaining undeveloped parcels.

In an appeal for reconsideration filed May 6 with the Oregon Bureau of Labor & Industries, an attorney for Eugene Riverfront District LLC, the company developing the housing, said the state’s position threatens the development of the remaining parcels in the project.

The threat: that developers will have to pay Oregon’s prevailing wage rate—i.e., union wages—and meet cumbersome, expensive reporting requirements on the unbuilt plots of land. Typically, the law requires developers to pay prevailing wage on public works projects or affordable housing projects funded by more than $750,000 in public money or that are more than four stories tall.

The Eugene Riverfront project isn’t any of those things (although developers plan some affordable housing in later stages). Instead, the dispute is over planned development that would be, like the Portal, market-rate housing built with private capital.

But the threat looms anyway because of a ruling BOLI made in 2021 on the project. In that ruling, the agency determined that because the city of Eugene will spend $35 million to install streets, utilities and parks that benefit the 16-acre parcel, the entire development, including all private development, should be considered a public works project and thus subject to Oregon prevailing wage rate law—even if some parcels aren’t developed for many years.

In other words, the agency said, anything that benefits from publicly funded improvements is subject to the same requirements as the streets and utilities for which the city paid. That means the same wages, adding what some experts say could be 10% to 20% in additional costs.

As OJP has reported, BOLI determinations on affordable, i.e., government subsidized, housing projects all over the state have also tilted in favor of organized labor, making the projects more expensive and sometimes infeasible (“A Little Off the Top,” WW, April 2).

Oregon’s prevailing wage rate law allows BOLI to issue a “split determination,” i.e., find that the public portion of the project is subject to prevailing wage but the privately funded portion is not. But the bureau, under the leadership of then-Labor Commissioner Val Hoyle, declined to do that.

Hoyle, who represented Eugene in the Legislature prior to being elected labor commissioner and now U.S. representative for Oregon’s 4th Congressional District, could not be reached for comment.

The attorney who filed the objection last week, Dina Alexander, says BOLI got the Eugene project wrong—and that could have consequences.

“The vertical development of the remaining parcels is expected to create much needed additional housing,” Alexander wrote. “However, if BOLI continues to take the position that vertical development of the remaining parcels is subject to prevailing wage rate law…the remaining parcels will likely remain unimproved.”

In other words, the parcels the developers are scheduled to buy from the city in coming years could lie fallow.

That would be a loss for Eugene, which, like most Oregon cities, is desperately short of housing. It could also create a roadblock for other cities across the state, including Redmond, Springfield and St. Helens, which are pursuing public-private partnerships they hope will deliver housing and economic development to their citizens.

“If BOLI continues to apply prevailing wage rate law to vertical construction arising from public/private partnerships in accordance with the prior determination,” Alexander wrote, “many large-scale vertical development projects will likely become financially infeasible, or the size and density of the projects may be significantly reduced.”

City officials in Eugene began working with the Eugene Water & Electric Board two decades ago to find a better use for the board’s 16.6-acre waterfront headquarters. The utility had shuttered a 1930-built waterfront steam generation plant and used much of the rest of the property to store equipment and park its trucks. It was an industrial barrier between downtown and the university. “Many cities across the country have former utility yards along their waterfronts and riverfronts,” Mayor Knudson says. “The most forward-thinking cities are repurposing these valuable spaces for civic use.”

In 2017, the city signed an exclusive agreement with a company led by Dike Dame, a Portland developer instrumental in the creation of the Pearl District and South Waterfront. In 2018, the city bought the EWEB property and set about both moving City Hall into the utility’s headquarters and preparing the rest of the property for redevelopment (the city later purchased the headquarters building and an adjacent parking lot in 2023).

Dame declined to comment because of his LLC’s pending BOLI appeal. But Homer Williams, who partnered with Dame on the Portland projects, says he’s aware of his former partner’s plight.

Williams says although the city of Portland invested hundreds of millions of dollars in the Pearl and South Waterfront, there was never any discussion that the privately funded vertical development should be subject to prevailing wage rates. (BOLI notes that both projects preceded a 2007 law that defined public works projects as anything funded by more than $750,000 in public money.)

Those projects, Williams says, ultimately delivered jobs, thousands of units of housing, and many million of dollars in annual property taxes. He says he’s not sure BOLI’s prevailing wage process delivers similar public impact.

“It adds a lot of costs and complexity,” Williams says. “Frankly, it’s a racket. The unions win and everybody else suffers. We want to get housing built. In order to do that, there’s got to be a balance—but the current system is not working.”

Trade union leaders strongly disagree. In recent testimony on a bill that would expand Oregon’s prevailing wage rate laws, Robert Camarillo, executive secretary of the Oregon State Building and Construction Trades Council, explained the importance of the law.

“Prevailing wages serve a dual purpose,” Camarillo told lawmakers. “They ensure that workers are compensated fairly while also preventing contractors from undercutting each other by paying lower wages or exploiting workers.”

Christina Stephenson, the current BOLI commissioner, is an independently elected official. Her agency makes prevailing wage determinations in a quasi-judicial process administered by BOLI judges. If applicants don’t like the bureau’s initial determination, they can ask for reconsideration, as Dame and his partners in Eugene are doing for a second time. If they still don’t get the answer they seek, they may petition the Oregon Court of Appeals.

Stephenson notes her agency’s prevailing wage determinations have never been reversed there; developers say that’s because the appeals process is so slow and expensive that few appellants bother.

Stephenson told the Oregon Journalism Project through her spokeswoman, Rachel Mann, that BOLI follows prevailing wage laws as written. Mann adds that BOLI’s original determination on the Eugene project found that while the law allowed the bureau to consider the public and private parts of the project separately, a variety of factors convinced the agency the development should be judged as a single public works project subject to prevailing wage.

“Ultimately, BOLI found that it would be inappropriate to divide the project,” Mann says.

Stephenson’s fellow Democrat, Gov. Tina Kotek, has made increasing Oregon’s housing supply by 36,000 units a year a top priority. The state has fallen far short of that rate through her first two years in office. Meanwhile, Kotek has pushed policies mandating union participation in state-funded projects.

Kotek spokeswoman Roxy Mayer says her boss has no comment on the Eugene project. “The governor will continue to work on implementing the recommendations of her Housing Production Advisory Council, including having a thoughtful conversation in the future about the application of prevailing wage,” Mayer adds.

But city officials all over the state are watching the project in Eugene closely. Springfield, just upriver from Eugene, hopes to revitalize its stretch of the Willamette with a public-private partnership. Redmond, which has seen its population grow twice as fast as nearby Bend’s, is looking for a private partner to help with housing needs; and St. Helens, which hopes to develop a 23-acre parcel of Columbia River frontage, is in the market as well.

St. Helens city manager John Walsh says the site of a former veneer and plywood mill that dominated the city’s waterfront is a prime candidate for redevelopment, but the city needs help—including flexibility from BOLI.

“We have been tracking the Eugene project,” Walsh says. “The desired outcome here is a public-private partnership, and BOLI will definitely be part of the process.” Although, Walsh adds, “It seems like BOLI determinations are getting less developer friendly.”

BOLI’s Mann says the agency is weighing its response to the appeal for reconsideration on the Eugene project.

This story was produced by the Oregon Journalism Project, a nonprofit newsroom covering the state.