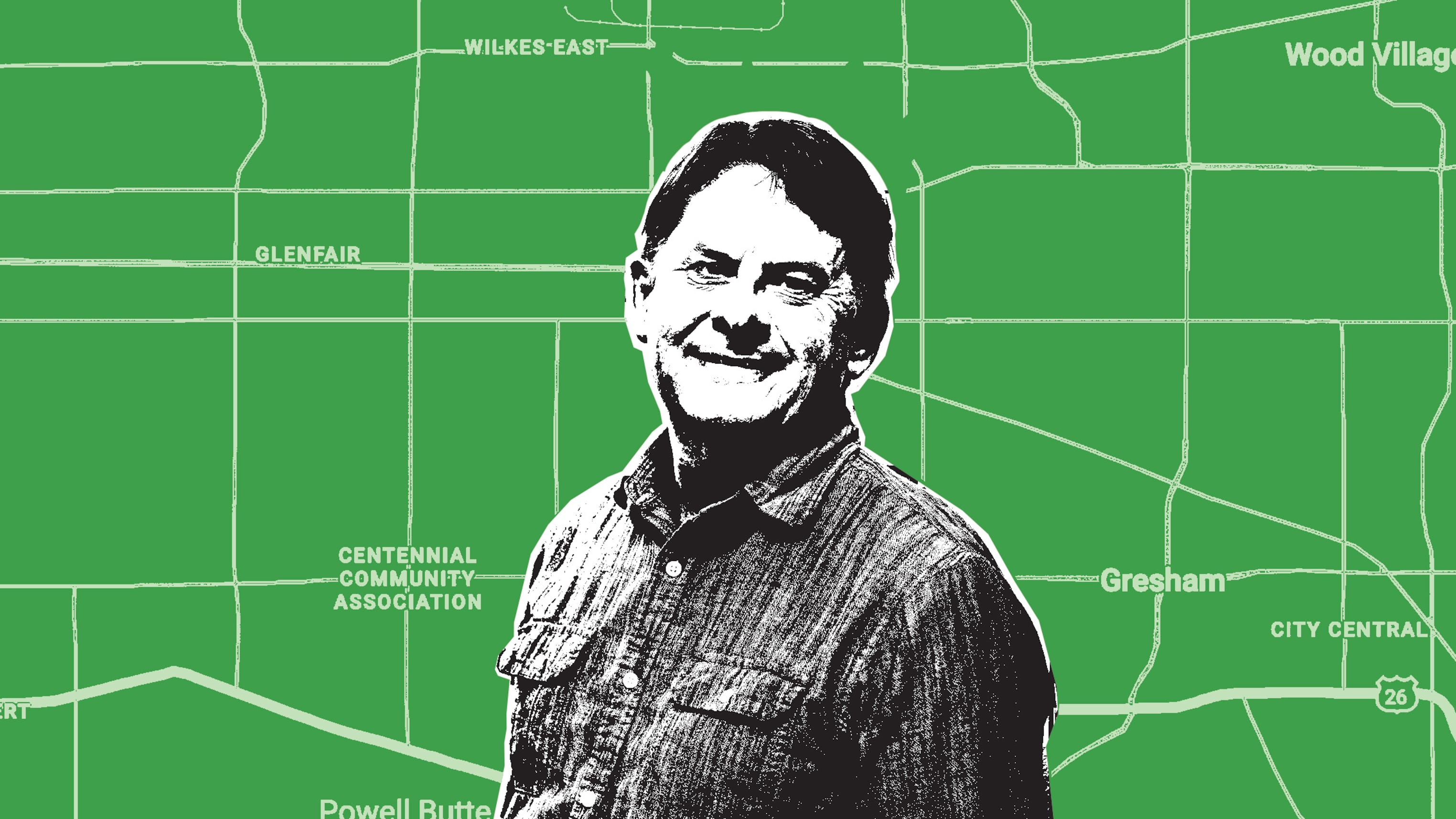

Rockwood is rough. Pull up a map of shootings in Gresham, and gray dots cluster in the rectangular neighborhood that stretches southeast from the corner of Northeast 162nd Avenue and Glisan Street to 202nd Avenue in the east and Market Street to the south.

That’s Rockwood, where about 40% of residents earn less than $29,000 a year and 70% of kids qualify for free or reduced-price lunch, according to Multnomah County figures. Those statistics explain why the state of Oregon went into business with Brad Ketch.

Talk to just about anyone who works in social services in Gresham and they’re likely to know Ketch, a onetime technology executive who grew up nearby. He and his wife, Lynn, founded the Community Development Corporation of Oregon, which does business as Rockwood Community Development Corp. He’s a longtime friend of new Multnomah County Commissioner Vince Jones-Dixon (whose brother was gunned down in Rockwood in 2013) and gave $568 to Jones-Dixon’s campaign last year.

Ketch made his biggest score in 2021, when he won a $6.8 million grant to purchase a tattered Best Western hotel on 181st Avenue and turn it into a family shelter. The cash came from Project Turnkey, a $125 million pot of state money allocated to purchasing hotels and turning them into shelters for people forced out of their homes by fires and pandemic-related poverty.

The state called on the Oregon Community Foundation, a highly respected grantor, to distribute the funds, betting OCF could do it quickly. Betsy Johnson, then a Democratic state senator from Scappoose, railed against the plan, getting crosswise with Gov. Kate Brown.

“Given my concerns about the cost, the initial and continuing oversight, and the speed with which the dollars were being deployed, I referred to it as Project Turkey,” Johnson says.

In the case of Ketch’s project, now called Rockwood Tower, Johnson’s concerns may have been prescient. Earlier this year, Multnomah County stopped paying Ketch to shelter 40 families, alleging that Rockwood CDC had billed for unapproved expenses, double-counted some costs, and charged the county for rooms under repair (“Best Western Front,” WW, June 25).

The county didn’t make the move lightly. Rockwood Tower accounts for almost half of the family-shelter rooms countywide. One couple and their toddler had to move to a hotel shelter near Mall 205, which has lengthened the mother’s commute and ruined her daughter’s sleep.

Ketch denies all of the county’s charges. He says it was Rockwood CDC that severed ties because the county owed it $1.1 million in overdue payments. The county says it has paid up.

But WW has learned over the past month that other government agencies clashed with Ketch over his accounting and business practices. A trove of emails and documents obtained by WW show that Ketch has been slow to produce financial statements for his board members, has struggled to pay rent on buildings, and failed to certify his nonprofit status with Multnomah County when asked to do so by Gresham officials.

That raises questions about the state’s due diligence on one of its highest priorities: putting roofs over the heads of vulnerable families.

OCF spokesman Colin Fogarty says the foundation has no oversight over grantees and referred WW to the Oregon Department of Administrative Services, which didn’t comment.

In response to WW’s questions, Ketch largely chalked up any irregularities to the threat his work posed to local officials who would rather gentrify Rockwood than aid its poorest residents.

For Ketch, Rockwood is tantamount to Calcutta. He says so in his 2023 book, The Flourishing Community: A Story of Hope for America’s Distressed Places. Like the poor sections of Calcutta, Rockwood is a stone’s throw from wealthy enclaves, and the disparity galls him.

His commitment still impresses Jones-Dixon, the county commissioner.

“The Rockwood CDC has been one of the driving forces behind the revitalization of Rockwood, ensuring our underserved communities have access to the services and opportunities needed to break the cycle of poverty,” Jones-Dixon said in an email to WW. “The relationship has not always been perfect, but we have been able to work through issues to produce positive outcomes for the Rockwood community.”

Ketch’s zeal convinced Mary Edmeades, a longtime vice president at Albina Community Bank who joined his board and later became chair because she grew up in Gresham, went to Centennial High School, and wanted to give back.

“Brad was going to save the world and save Rockwood,” Edemeades says.

But Edmeades, who knew her way around financial statements, says she couldn’t get any from Ketch. It was “baffling,” she said in an email to him on Dec. 4, 2017. “We are approaching the end of the year with no good understanding of where we financially sit.”

Edmeades badgered Ketch for months but never saw a bank statement, she says. At wit’s end, she resigned. “I no longer have any confidence that the organization is operating with financial integrity and for community benefit,” Edmeades wrote on Dec. 14, 2017.

“Things just got crazy,” Edmeades says. “I don’t know how to say it any other way.”

Asked about the matter, Ketch referred WW to his book, where he says that his board chair (he doesn’t refer to Edmeades by name) told him he “had gotten too close to entrenched interests and that she could not personally afford to be viewed as a threat to them.”

Ketch exasperated government officials, too. In 2015, a Rockwood restaurant called the Black Cat Cantina closed, and Ketch got word that it would reopen as a strip club, he writes in his book. Ketch called the owner and convinced him to lease the building to him for a year while he tried to raise $1.35 million to buy it. Lease in hand, Ketch set up the Sunrise Center and invited other nonprofits to use the kitchen and space.

But Ketch raised just $5,000 for his capital campaign. Fortunately, the Gresham Redevelopment Commission came to the rescue, using a windfall of capital to buy the place, Ketch writes.

When it bought the building, the commission paid $16,372.58 in taxes. If tenants were nonprofits, the commission could get that money back. The job fell to a commission employee named Cecille Turley, who emailed Ketch on Oct. 28, 2016, and asked him to file with Multnomah County to prove that Rockwood CDC was indeed a nonprofit for the year ending June 30, 2017, emails show. Ketch wrote back and said Rockwood CDC was already exempt in the eyes of the county, according to Turley’s account.

Unsatisfied, Turley contacted Multnomah County and confirmed that the CDC wasn’t exempt. She sent Ketch the county form he needed to complete on Nov. 4, 2016, according to an email obtained by WW. “Getting that done quickly is very important to our bottom line,” Turley wrote.

Ketch said he would file but didn’t have enough cash to cover a $2,000 late fee. The commission found a work-around, the memo says. It would pay the fee and bill the $2,000 back to Rockwood CDC as “additional rent.” Turley asked Ketch to send her a copy of the application. He never did, she says in the memo. Because Ketch missed the deadline for filing, the commission didn’t get its $16,372.58 refund for that tax year.

Ketch says he paid the taxes in question. The Community Development Corporation of Oregon was a nonprofit then, and it did business as Rockwood CDC, so there was no issue, he says.

Ketch had trouble paying rent, too, according to the Gresham Redevelopment Commission. In November 2017, the commission wrote to Ketch, summarizing their dispute: Rockwood CDC owed $2,757.10 in back rent, plus an unpaid security deposit of $2,000.

During the fight, Ketch said the commission had failed to pay Rockwood CDC for social services it provided. The commission said it could find no unpaid invoices.

“We cannot substantiate your claims of unpaid invoices to the Rockwood CDC, which is a separate issue from the past due balance of rent, security deposit, and property tax liability related to your lease,” the commission wrote.

Ketch says the city of Gresham was trying to force him out of the building for nonpayment of rent because the city wanted to tear it down and redevelop the property.

Despite these irregularities, the Oregon Community Foundation elected to grant Rockwood CDC $6.8 million to buy the old Best Western. OCF relied on an advisory committee “with expertise in and lived experience of housing insecurity, which vetted applicants and selected grantees,” according to a 2021 report on the program sent to the Oregon Legislature. OCF also retained two real estate consultants who examined the properties, the report says.

There is evidence that the foundation knew about Ketch’s accounting issues. In January 2022, his attorney, Brian Jolly, wrote to Gresham City Councilor Dina DiNucci, insisting that she recuse herself from any matters involving the Community Development Corporation of Oregon, Ketch’s main nonprofit, because she had opposed granting it the Project Turnkey money.

“You called OCF the night before the press conference to try and get the grant stopped,” Jolly wrote. “You told OCF that the CDCO was not trustworthy.”

In his book, Ketch says the hotel grant lifted the Community Development Commission of Oregon into the top 5% of all U.S. nonprofits by budget and “signaled to everyone that we had arrived as a real player in community transformation.”

Ketch’s salary reflects that. Rockwood CDC paid him $228,223 in 2023, according to a filing with the federal government. His wife made $143,440. One of his sons works there, too.

In 2022, Multnomah County officials started sending Ketch families in need of temporary shelter. Three years later, they, like Edmeades and DiNucci, determined that Ketch’s accounting was so troubling they would disrupt 40 families by relocating them once again.

Edmeades said she’s not surprised. “Brad is really smooth,” she says. “He speaks with a ton of confidence. He leads you to believe that he’s the resident expert. But there is a dark side.”