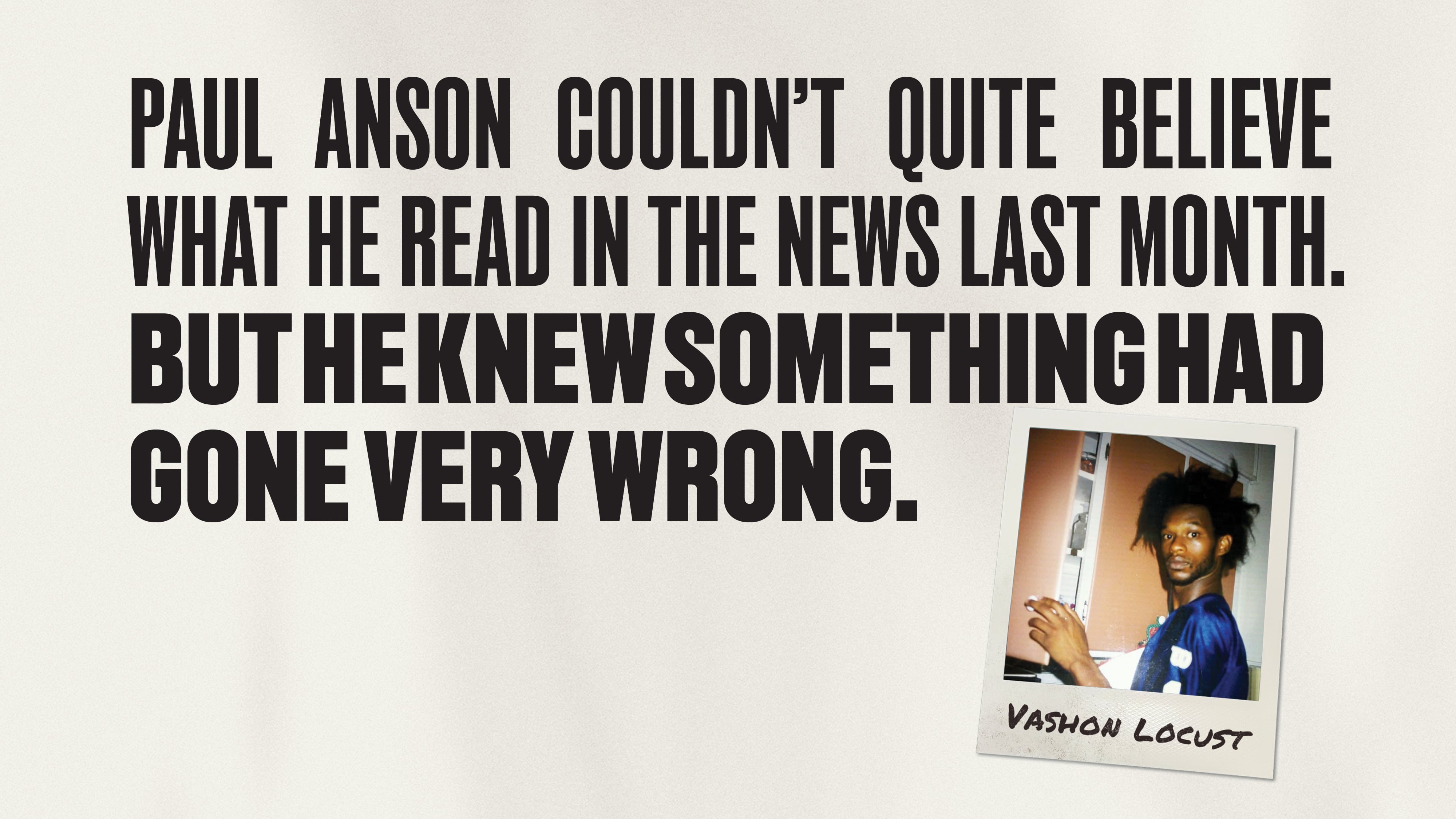

Paul Anson couldn’t quite believe what he read in the news last month. But he knew something had gone very wrong. Vashon Locust had been arrested for the Oct. 26 fire that damaged Portland City Councilor Candace Avalos’ home and car and transfixed local officials.

Anson, who owns Landfill Rescue Unit Records on Southeast Belmont Street, remembered attending an addiction treatment program with Locust in 2008. He recalled Locust having a brilliant smile, and a passion for basketball and Nirvana.

Their paths diverged. Anson got sober, found a serious girlfriend and a downtown apartment. Around 2010, he recalls, he saw Locust at a known drug-dealing spot on Northwest Flanders Street. “I thought, ‘Damn, this sucks. He’s just stuck. He’s out here in the same place, doing the same thing.’”

For a week after the Avalos fire, local politicians speculated whether the blaze was a targeted arson, perhaps part of the rising tide of politically motivated violence against elected officials.

Once it became clear that this wasn’t the case—that the fire was in fact started accidentally in a nearby shed by a chronically homeless man trying to stay warm—public attention wandered elsewhere.

Yet a review of court records in Oregon and Michigan, psychological evaluations, and interviews with those who have known Locust dating back four decades reveal that the real story is one that is all too common in Oregon.

It’s about a polite little boy in Flint who fled his troubled mother’s house at 9 years old and was taken in by a family living across the street. It’s about a young man whose passions for music and basketball were in time overwhelmed by drug addiction and acute mental illness, leaving him deeply vulnerable—and Portlanders terrified.

And perhaps most of all, it’s about a dysfunctional system that fails to hold people like Locust accountable, get them well, or keep them safe.

This is not for a lack of chances. While no small part of the past two decades of Locust’s life has taken place on the streets of Portland, he also spent periods in shelters, in jails, in stable housing, in prison, in transitional housing, and—at least twice, after a judge found him unfit to stand trial—Oregon State Hospital, the state’s highest-acuity psychiatric care facility.

But Locust, now 52, always ended up back on the streets. The path to that cold shed was one he traveled over and over.

WW attempted to reach Locust and his court-appointed defense attorney. Neither responded.

One day in Flint, Mich., in the early 1980s, a young boy asked Karla Mance, a mother of four children, if he could stay the night at her house. The boy, Vashon Locust, had just moved from Portland with his mother into his grandparents’ house across the street, and he and Mance’s son Robert had become fast friends. Mance knew Vashon’s mother, Labrenda, was involved in prostitution and drugs (court records show she was arrested regularly for prostitution and was just 15 when she had Locust), and Mance had come to enjoy having Locust in her home.

Before long, Locust started staying over regularly. “One time he came and spent the night and he never went home,” Mance, 69, tells WW. Mance lives in Flint to this day. “We didn’t have a lot,” she says, “but we had love in the house. And we had room for one more.”

Within a year, Mance says, Labrenda came to her house with two men and said she was moving to Atlanta and taking Locust with her.

“I said, ‘OK, Labrenda, he’s your child, I understand,’” Mance recalls. “But it kind of broke my heart because I got used to him being there.”

Locust would later recall this period with a psychologist. “We moved to Georgia and my mom fell into crack cocaine, and it was hard times,” he said, according to a 2017 evaluation included in a subsequent court record.

Soon after, Labrenda and an 11-year-old Locust returned to Flint. She dropped him off at Mance’s home and kept driving, Mance recalls.

He stayed with Mance’s family through his teens. Locust told the psychologist in 2017 that Mance was one of the few people in this world that he trusted.

Despite the deprivations of his upbringing, Mance recalls that Locust was well mannered and polite, a straight-A student. She says Locust was “the type of child that anybody would love to have.” And her two youngest girls loved him like a big brother.

Locust would cook for them while singing Prince songs, one of those little sisters, Adrianne White, recalled in an interview with WW. “He really loved us. No one could tell me that wasn’t my brother.”

Locust had two misdemeanors on his record in his early 20s while living in Flint, but it’s unclear exactly when his serious troubles began. In a 2017 psychological evaluation, he said he arrived in Portland around 2006 (“I was living in Anaheim, and I met a young lady. She asked me if I wanted to come to Portland”), and his run-ins with the law soon started.

Multnomah County court records show dozens of charges against Locust since 2006. Felony cocaine possession in 2006 and 2010. Delivery of cocaine in 2013. Criminal trespassing in 2007, 2010 and 2021. Others for burglary and theft.

He served sporadic prison time, but most of his run-ins with the law were misdemeanors or nonviolent felonies. A cycle emerged: Locust would get arrested, booked into jail, arraigned and then released pending his next court date. Sometimes he would plead to a charge or be found in violation of probation and, following sentencing, the judge would nudge him toward treatment (it is unclear how often he could actually get in). Oftentimes he would fail to show up to court.

There is a county system for making sure people show up for court dates. Corrections deputies or technicians check in by phone and send appointment reminders. Sometimes it requires an electronic ankle monitor. It doesn’t always work. Close Street, the pretrial supervision program that focuses on defendants deemed unlikely to show up to court, reported in 2025 that 50% of defendants fail to show up for their first appointment.

When Locust didn’t show up, a judge put out a warrant. Eventually, he’d get arrested again.

Multnomah County lists no new charges against him between late 2007 and mid-2010. That’s when Anson saw Locust in drug treatment at LifeWorks NW. According to Locust’s account in the psychological evaluation, it’s also when Locust attended college classes—at Heald College, and Portland Community College, where he hoped to study sports analysis and music.

By 2010, though, the charges resumed. That year he sold cocaine near a school, and after one too many probation violations in that case, a judge sent him to prison in 2013.

He received some treatment there. He told staff he heard voices, and was prescribed a medication—what specifically he could not recall to the evaluator. But after his release, Locust would later recall, he started using again, first crack cocaine and then methamphetamine. “Weird stuff started to happen,” he would later say to the evaluator. “I felt like I started to be set up.”

Over the years, Locust spent time at a handful of shelters and transitional housing, like the Estate Hotel in Old Town—a drug- and alcohol-free program—and the Portland Rescue Mission on West Burnside Street. He also started breaking into people’s homes.

Sometimes the homes would be empty, sometimes not. He’d break in to take a shower, or to charge his devices, or just to rest.

In the summer of 2016, a man returned to his home in the Goose Hollow neighborhood to find Locust preparing to take a shower. Three weeks later, Locust tried to crawl through a window of the same apartment. The following year, another Goose Hollow man called the cops on Locust after he broke into his apartment and stole a laptop. Two weeks later, the same man’s landlord called police after he found Locust squatting in an adjacent unit.

In June 2021, a woman in a North Portland home awoke to her dog barking and a commotion outside her bedroom door; she told officers she remained frozen in her room for 10 minutes before walking out to find Locust in her bathroom.

A cleaning lady entered a North Portland home in 2022 and found Locust in a second-story bedroom. An apartment manager in spring 2023 opened the door of a vacant unit in the Waterline Apartments to show to two prospective tenants. Inside she found Locust.

By 2017, Locust had spent 11 years living in Multnomah County, and law enforcement and health officials had a clear picture of his struggles with mental illness and addiction.

After one arrest that year—for burglary, trespassing and theft—a psychologist, Dr. Alexander Millkey, assessed Locust in jail.

Millkey’s report was included in a subsequent court record. It provides an unusually clear window into Locust’s mental state and daily life.

Millkey found Locust to be a “complex case.” Superficially, at least, Locust did not appear psychotic, and was instead lucid, polite and at times childlike in his earnestness. When asked about drug use, Locust told Millkey, “I don’t really do crack cocaine anymore. I mean, I would smoke some if you had some!” At another point, Locust said he felt pretty physically healthy, though he conceded that he couldn’t “bend all the way down and touch my feet.” He had three children but didn’t have a steady relationship with any of them.

Locust said he was a damn good dishwasher, and he liked to write and rap. He’d recently worked as a traffic director for the Portland Trail Blazers during home games, he said, and for fun he played basketball and took down detailed statistics of games. (Anson recalls Locust telling him that’s what he did when he was high. “He’d just stay up crunching numbers, obsessively,” Anson says. “Up all night. That’s what gave him pleasure when he was loaded.”)

Yet in the interview, the psychologist also recorded signs in Locust of hallucinations and delusional paranoia. Locust, according to Dr. Millkey, believed he was in a movie, that his legal situation was part of the movie, and that he intended to base his legal defense on this belief. Citing this “Truman Show Delusion,” Millkey diagnosed Locust with a psychiatric disorder in the schizophrenia spectrum, and added a meth and cocaine disorder. He wrote that he believed Locust was unfit to proceed to trial.

A judge agreed. In July 2017, Locust was admitted to Oregon State Hospital, having been found unable to aid and assist in his own defense.

As WW has documented in some detail (“Revolving Door,” March 1, 2023), there is perhaps no better expression of the state’s mental health and addiction crisis than the glut of people accused of crimes but found unfit to stand trial.

In 2012, Oregon courts issued about 30 orders per month sending defendants to Oregon State Hospital after finding them unable to aid and assist in their own defense. By 2025, state data shows, the monthly rate had more than tripled, to 99.

Why this has happened—why the aid-and-assist population has swelled and swelled—remains for even the system’s closest observers a matter of debate. “That is the million-dollar question,” says Heather Jefferis, executive director of the Oregon Council on Behavioral Health.

Yet such patients keep coming. This fact, observers say, has dramatically changed the character of acute residential psychiatric treatment in Oregon, and perhaps nowhere more so than at the state hospital itself, which has its main campus in Salem. In 2000, defendants unable to aid and assist made up less than 10% of its patient population. Now they easily constitute the majority (see graph below). Their stays are often shorter, restrictions tighter, conditions graver, their connections to the outside world more tenuous.

“Most of them don’t have anybody that ever comes to visit them,” says Rick Snook, who worked at the hospital as its patient population transformed and now sits on the board of its historical museum. “Most of them never receive a phone call from anybody.”

The hospital’s operations have been shaped in key ways by a lawsuit—now active for more than two decades—which pressures the state to keep aid-and-assist patients moving through the system swiftly, releasing them after limited periods so that the next batch don’t languish too long in jail waiting for a scarce bed to open.

For aid-and-assist patients, the objective of the hospital is, medically speaking, somewhat narrow: to return them to a level of competency that might allow them to be tried for their crimes. “It’s such a low bar,” says Chris Bouneff, executive director of Oregon’s chapter of the National Alliance on Mental Illness. “You won’t get healthy again. You will be restored to enough capacity that we can prosecute.”

In September 2017, another clinician, Dr. Terri Fernandez-Tyson, interviewed Locust at Oregon State Hospital to determine whether he had been restored to competence to defend himself in court. It had been a rocky go at the hospital. He’d been noted at intake to be experiencing auditory hallucinations and have paranoid delusional beliefs. Three times he’d been subsequently put in seclusion, “precipitated by acts of aggression.” And he’d had to be “medicated on an involuntary basis.”

Fernandez-Tyson echoed Millkey’s determination that Locust suffered from schizophrenia. But she found that “Mr. Locust had responded favorably to treatment with antipsychotic medications,” and her Sept. 6, 2017, report found Locust fit to proceed to trial. On this basis, a judge moved forward with the case. Less than two weeks later, a court record says Locust was “back from the OSH,” and, on Nov. 21, a court routed him to transitional housing as his legal case proceeded.

Then, almost immediately, he disappeared.

Hours after signing conditions of release, Locust “failed to return” to the treatment facility by an 8 pm curfew, court records show, and “has not charged his GPS bracelet since that time.” Eventually, police tracked him down. On March 6, 2018, he pleaded guilty to burglary and criminal trespass, acknowledging he’d twice entered Southwest Portland residences in April the previous year. A judge sentenced him to prison.

It is unclear how long he spent there, but within seven months, new criminal charges had been filed against Locust in Multnomah County, for trespass and meth possession.

The cycle renewed in 2023. At various times that year, Locust was arrested on charges of burglary and criminal trespass. Dr. Millkey interviewed him again, though the encounter this time lasted just 15 minutes before Locust cut it short. In December 2023, Judge Nan Waller of the Multnomah County Mental Health Court sent Locust back to Oregon State Hospital, determining he was, once again, unable to assist in his own defense.

Within weeks, according to court records, OSH told the court that Locust no longer needed a “hospital level of care” to regain fitness for trial. So he was released to the Northwest Regional Re-entry Center—a halfway house, if you will—out by the airport. Vashon “absconded shortly after arrival,” Waller wrote in a March 5 order. He didn’t show for his next trial date, and by August 2024 he’d been arrested again.

By this point, Judge Waller could see few good options. Locust was still unfit to stand trial on the original burglary charges. Based on an evaluation by the county’s forensic diversion program, Waller wrote, Locust was “not a good candidate for community restoration,” so a residential treatment home was not on the table either.

Meanwhile, the last alternative, Oregon State Hospital, was evidently no longer an option. “The defendant,” the judge wrote, “has already been to the OSH under these charges and cannot be returned for additional restoration services.”

In short, the system had determined Locust was too ill to stand trial, but could find nowhere else to send him to help him get well. Locust’s defense counsel moved to throw out the criminal cases against him, and the state took no position on the matter. “In the interest of justice,” on Aug. 20, 2024, Waller dismissed all charges.

Waller, speaking in general about her mental health docket, said in an interview with WW that having so few options for high-acuity people is frustrating.

“The hardest thing as a judge is when someone is really struggling and I have no options,” Waller says. “Nobody wants to send somebody out on the street doing poorly, but the law requires certain things, and it’s my obligation to follow the law.”

Related: Oregon’s Plan for Fixing Its Mental Health System: Build More Beds, Get More Workers.

Asked for comment for this story, local and state officials affirmed that the system is broken and outlined visions for transforming it. “No one believes the status quo is working for our most vulnerable neighbors,” wrote Multnomah County spokeswoman Sarah Dean. “We have been advocating for, and implementing, programs and strategies that will create a cohesive, low-barrier system that can break the cycle of homelessness, crisis and incarceration.”

Locust’s story, wrote Lucas Bezerra, a spokesman for Gov. Tina Kotek, “is a sobering reminder that our systems of support need consistent oversight and investments to improve.” To this end, he says the governor seeks to build out treatment capacity and the health care provider workforce. He also noted the governor’s support for a bill set to soon go into full effect that will make “it easier for those who don’t know that they are struggling with mental illness to receive treatment rather than court-ordered restoration that merely prepares one to stand trial.”

A year after Waller dismissed Locust’s charges, and a week after a fire damaged the home of Councilor Avalos, Portland Police Bureau officers arrested him on Nov. 4.

He told them what had happened. On the night of the fire, he was cold and wet, and had entered the shed to plug in a portable heater. When it didn’t work, he lit a fire to warm himself. The fire got too big. Locust tried to extinguish it, then fled to a nearby church. The blaze destroyed two cars and the side of Avalos’ home.

Prosecutors charged Locust with reckless burning, criminal mischief and criminal trespass. And as the headlines went away, the cycle began again.

The judge, Rebecca Lease, released Locust on Nov. 6 and told him to show up for court on Nov. 21. He didn’t show. Judge Benjamin Souede signed a bench warrant for Locust’s arrest. He is still at large.

Across the city, across the country, those who have known Locust seek to reconcile where he has been with where is now.

Sitting on a stool on a Saturday morning at the back of his records store, with melancholic grunge music softly playing in the background, Anson wonders why Locust was the only person from that basement recovery program that he still remembers. “He just had a charm,” Anson says.

Out in Flint, meanwhile, Locust’s godmother and little sister worry. Over the years, in comments left on Locust’s spotty Facebook posts, they implored him to return to Flint.

White, Locust’s little sister, says she doesn’t want people thinking Locust is a mean person. “I don’t want anyone to think he was trying to cause damage to anyone or anything,” White says. “With a little love, you could see who he really is under all of that.”

“I know Vashon is still in there somewhere,” Mance adds. “God knows I love him.”

This reporting is supported by the Heatherington Foundation for Innovation and Education in Health Care.